Bolivia - Part 2 of 2: Salar de Uyuni and 4x4 Offroading Andes Altiplano to Chile over Hito Cajón Mountain Pass

Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: The world's largest salt flat, spanning over 4,086 square miles of the Bolivian Altiplano

Alright, buckle up, buttercups. After we finished part one of our Bolivian bonanza - which involved not falling out of a reed boat on Lake Titicaca and staring at ancient rocks in Tiwanaku (seriously, go read Part 1, it's good for you) - we pointed our travel-hungry noses toward Uyuni. The mission? To drive across the world's largest salt flat, the Salar de Uyuni, like a bunch of modern-day explorers, but with significantly less dysentery and much better Instagram opportunities. This included sleeping in hotels made of salt (licking the walls is optional, but tempting) and a multi-day, off-road 4x4 saga across the Andes altiplano and the Atacama Desert, all the way into Chile. It was less "Thelma & Louise" and more "Family Truckster on a geologic bender."

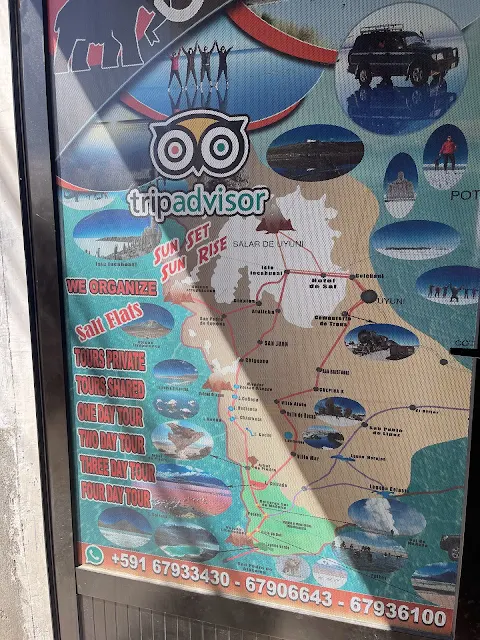

Here is a map of this part of our trip. I promise it's more exciting than the map of your local mall.

December 28, 2022

10:30 AM

Uyuni, Bolivia (20.4° S, 66.8° W, altitude 12,024 feet)

Our day started with the kind of enthusiasm usually reserved for root canals. We dragged ourselves out of bed at 4 AM for a 7:30 AM flight on Boliviana De Aviación from La Paz to Uyuni. Why so early? Because getting into Bolivia took approximately three ice ages at immigration (a thrilling saga detailed here), and I wasn't taking any chances. The check-in agent was confused we didn't have a guide and assigned us a minder, who periodically checked on us like we were escape-risk toddlers. The flight itself was lovely, with a layover in Cochabamba, though they confiscated our last aerosol of Lysol, declaring it a "fire hazard." I guess they've never seen me try to cook. The real show began on final approach to Uyuni's Joya Andina (Jewel of the Andes) airport, where we got our first mind-bending glimpse of the Salar de Uyuni - a salt flat so vast it could swallow the entire country of Lebanon and still have room for dessert.

Uyuni Joya Andina Airport Final Approach

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bzoal_4_V1s

Geographical & Geological Sidebar: The Altiplano Playground Welcome to the Altiplano, a high plateau nestled between the eastern and western cordilleras of the Andes, averaging about 12,000 feet in elevation. This isn't just a big, flat, windy place. It's a complex basin that's been filling up with sediment, volcanic ash, and evaporated goodness for millions of years. The Salar de Uyuni is its crowning, salty jewel. It was formed when a giant prehistoric lake, Lake Minchin (and later Lake Tauca), evaporated like a forgotten puddle, leaving behind a crust of salt up to 30 feet thick in places. Beneath that crust? A soupy brine rich in lithium, magnesium, potassium, and boron. In fact, this single salt flat holds over half the world's known lithium reserves. So, when you're charging your fancy electric car, thank this bizarre, beautiful, and brutally bright white desert in Bolivia.

Salar de Uyuni from final approach to Uyuni Airport, Bolivia: Aerial view of the vast white expanse from the airplane window

The hospitality was top-notch, a genuine warmth that feels different from the scripted nice-ness you often get elsewhere. We collected our bags (miraculously, all there) and found our driver holding a placard outside. We were whisked away in a Toyota Land Cruiser toward our home for the night: the legendary, salt-constructed Hotel Luna Salada de Sal & Spa. On the way out of town, we passed a manual security checkpoint/toll booth where the attendant had to physically heave a lever to open the gate for each car. It was a solid bicep workout and probably the most secure gate in Bolivia, given the effort required.

Uyuni Joya Andina Airport, Uyuni, Bolivia: Modern terminal building at high altitude

Uyuni Joya Andina Airport, Uyuni, Bolivia: walking to arrival/departure hall

Uyuni Joya Andina Airport, Uyuni, Bolivia: View of the airport with arid landscape in the background

Cultural & Historical Pit Stop: The Town of Uyuni Nestled at a breath-stealing 12,000 feet, Uyuni wasn't always a tourism hub. It started as a trading post in the 1880s, thanks to its location at the intersection of trade routes from Argentina, Chile, and the Bolivian mines. Its real boom came with the railroads in the late 19th century, built primarily to haul silver and other minerals from the Potosí region to Pacific ports. That history is now literally rusting in its famous Train Cemetery. The town itself is a hardy, wind-swept place where the buildings are low and the people are resilient, having adapted to extreme conditions, economic shifts, and the whims of international mining markets. Today, its economy is buoyed by salt, lithium, and the endless stream of tourists like us coming to gawk at the great white nothing.

Checkpoint on Bolivia Ruta 30 towards Colchani from Uyuni: Manual gate control on the road out of town

The hotel was a half-hour drive northwest of the airport. The route took us on Ruta F30 and then onto a dusty, deserted dirt road from the village of Colchani. The area was eerily quiet, with closed gift shops - a sad, silent testimony to the gut-punch COVID-19 dealt to local tourism worldwide. It felt like driving through the set of a post-apocalyptic movie, but with better scenery.

Dirt road from Colchani to Salt Hotel, Salar de Uyuni, Uyuni, Bolivia: Deserted track leading to the salt hotel

Dirt road from Colchani to Salt Hotel, Salar de Uyuni, Uyuni, Bolivia: traditional handcrafts for sale

Dirt road from Colchani to Salt Hotel, Salar de Uyuni, Uyuni, Bolivia: Close-up of the rough, dusty path

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada: the hotel made of salt

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Wide panoramic shot of the hotel exterior

This place had been on our bucket list ever since National Geographic taunted us with this video back in 2015. A hotel made of salt? On the edge of the world's largest salt flat? Sign us up. We finally saw the sign on the dirt road, took a right, and climbed a hill to find this architectural marvel made of compressed salt bricks, salt mortar, salt floors, salt furniture... you get the idea. It's like the Gingerbread House, but for people with high blood pressure.

Natgeo coverage of Hotel Luna Salada

Social & Architectural Deep Dive: The Salt Hotel Phenomenon Building with salt isn't just a gimmick; it's a practical use of the most abundant local material. The blocks are cut from the Salar, compressed, and bonded with a slurry of salt and water (effectively making a "salt cement"). The first salt hotel, Palacio de Sal, opened in the mid-90s but faced environmental issues (imagine the sewage system... or don't). Newer hotels like Luna Salada and Cruz Andina have more sustainable designs. The thermal properties are interesting: salt is a poor insulator, but the thick walls and incorporation of local volcanic rock (which absorbs daytime heat) help moderate the extreme temperature swings of the altiplano. Staying here is a lesson in adaptive architecture, where necessity and novelty meet in a crusty, crunchy, and surprisingly cozy package.

Dirt road from Colchani to Salt Hotel, Salar de Uyuni, Uyuni, Bolivia: Approaching the hotel with the salt flat visible ahead

Dirt road from Colchani to Salt Hotel, Salar de Uyuni, Uyuni, Bolivia: Another view of the desolate road leading to the hotel

Dirt road from Colchani to Salt Hotel, Salar de Uyuni, Uyuni, Bolivia: Rocky and dusty terrain near the hotel entrance

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - View of the hotel's main entrance and salt-brick architecture

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Close-up of textured salt walls and windows

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Interior salt-brick corridor with rustic lighting

View of Salar de Uyuni from Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Panoramic vista of the salt flat from a hotel window

Dirt road from Colchani to Salt Hotel, Salar de Uyuni, Uyuni, Bolivia: View back down the road toward Colchani village

Dirt road from Colchani to Salt Hotel, Salar de Uyuni, Uyuni, Bolivia: Final stretch of the road before reaching the hotel

Walking into the lobby was like entering a giant salt shaker designed by a very literal-minded architect. The floor crunched, the walls were gritty, the columns were lumpy, and even the couches dared you to lick them. And right outside the windows, stretching to infinity, was the Salar itself. It was utterly bizarre and completely awesome.

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Lobby area with salt-brick walls and rustic decor

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Another angle of the lobby showing seating area and salt textures

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Detail of a salt-brick column and wall texture

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - View of a lounge area with large windows overlooking the Salar

The hotel was enormous. Our family suite, which was basically a small salt-brick mansion, was a ten-minute hike away at the other end of the building. Thank every deity ever imagined for the bellhop, because dragging luggage at 12,000 feet is a special kind of torture. The guy earned his tip just by breathing normally while carrying our stuff.

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Long hallway with salt floors and wooden walkways

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Another view of the interior corridor showing salt-brick construction

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Cozy nook with seating and a view of the salt flat

On the way to our suite, we passed lounges and cozy nooks with jaw-dropping views of the Salar. The floor was loose granular salt with laminate walkways - presumably to prevent guests from leaving a trail of white footprints like confused ghosts. The walls were solid salt bricks, held together with what I can only assume was salty determination.

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - View from a lounge area with expansive windows and salt decor

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Seating area with salt-block walls and traditional textiles

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Another cozy corner with salt-brick architecture and wooden beams

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - View down a long salt-brick hallway with natural light

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Interior showing a salt-brick archway and rustic decor

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Vertical shot of a salt-brick wall with textured surface

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - View of a lounge with large windows and salt-block construction

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Another interior space with salt walls and traditional Bolivian artifacts

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Cozy seating area with a view of the salt flat through the window

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Detail of a salt-brick wall with embedded traditional craft items

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Another view of the hotel's interior showing salt-block architecture and decor

The hotel was also a museum of traditional Bolivian crafts, with beautiful artifacts everywhere. We spotted llamas and alpacas made of reed, reminding us of the incredible reed boat craftsmanship we saw on Lake Titicaca (seriously, go read Part 1, the plugging never ends).

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Display of traditional Bolivian reed crafts including llamas and alpacas

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Close-up of a reed llama sculpture, a traditional Bolivian craft

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Another angle of the reed craft display against a salt-brick wall

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Display case with traditional textiles and artifacts in the hotel

The family suite was practically its own zip code, with a private hallway, two bedrooms, and spacious living areas. It was the salt-brick palace of our dreams.

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Family suite living area with salt-brick walls and comfortable seating

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Bedroom in the family suite with salt-block headboard and rustic decor

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Another view of the bedroom showing salt-brick architecture and bedding

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Living area of the suite with salt-block walls and traditional textiles

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Additional seating area in the suite with a view of the salt flat

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Bedroom detail showing the salt-block headboard and nightstand

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - View from the suite's window overlooking the Salar de Uyuni

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Bathroom area with salt-block walls and modern fixtures

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Another view of the suite's living space with salt-brick details

Even the king-sized beds were made of salt. I'm not kidding. The headboard was a solid slab of the stuff. Luckily, there was enough laminate flooring to prevent midnight bathroom trips from turning into a painful salt-granule foot massage.

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Close-up of the salt-block headboard in the bedroom

Colchani

14:02

Colchani, Bolivia: The small salt-processing village on the edge of the Salar de Uyuni

We headed back to the village of Colchani, a speck on the map with a population just over 1000. For centuries, the Quechua people here have survived by harvesting salt, a back-breaking tradition that once involved llama caravans trekking over 350 miles across the Andes Altiplano to barter for essentials. Think of it as the original DoorDash, but with more spitting and way slower delivery times.

Colchani, Bolivia: Street view of the village with traditional buildings and salt-processing facilities

Now, things are a bit more modern. There's a cooperative, some machinery for iodization (because goiters are so last century), and trucks to ship the salt to Bolivia and beyond (Brazil is a big fan). We took a tour of a salt factory, which was less Willy Wonka and more "Science of Stuff That Makes Fries Taste Good."

Salt Bricks with layers showing rainfall: Stacked salt blocks displaying dark bands that indicate ancient rainfall patterns

Geological & Economic Deep Dive: The Salt of the Earth Let's geek out on salt for a second. The Salar de Uyuni isn't just a thin crust; it's a monster. The salt is at least 700 feet deep in the center (though some conservative estimates say 400 feet), covering over 4,086 square miles - that's larger than some countries. It contains an estimated 11 billion tonnes of salt. The Colchani cooperative extracts about 25,000 tonnes annually, which is like taking a single grain from a beach. The salt forms in distinct layers, each representing different climatic periods. The dark bands you see in salt bricks? Those are ancient rainfall, trapped in time like geologic tree rings. And it's not just table salt. This place is a treasure trove of lithium, potassium, boron, and magnesium. The "Lithium Triangle" of Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina holds about 75% of the world's lithium reserves, and the Salar de Uyuni is its crown jewel. Those compressed salt bricks aren't just for show; they're a legitimate, durable, and locally-sourced construction material used all over the region.

- The salt in Salar de Uyuni is at least 700 feet deep in the center, though the true depth is unknown and a lower depth of 400 feet is cited often.

- The largest salt flat in the world, the Salar covers an area of over 4,086 square miles.

- Of the at least 11 billion tonnes of salt in the Salar, 25,000 tonnes are extracted and processed every year at Colchani.

- There are 11 layers of salt ranging from 6 to 60 feet deep each. The top layer is around 32 feet.

- Rainwater results in salty brine collecting between the layers. The dark bands in blocks of extracted salt represent rainfall.

- Evaporating salt lakes 40,000 and 12,000 years ago left behind concentrated minerals in the Salar, including potassium, boron, magnesium and lithium.

- Salar de Uyuni by itself contains over half of the planet's lithium. Along with Salar del Hombre Muerto, Argentina and Salar de Atacama, Chile, 75% of the world's lithium deposits are in the salt lakes of the Andes altiplano.

- Compressed salt bricks are used for construction, including other salt hotels and buildings around the Salar.

Salt Factory, Colchani on Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Interior of the salt processing facility with piles of raw salt

Salt Factory, Colchani on Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Workers processing and bagging salt for distribution

Salt Factory, Colchani on Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Stacked bags of processed salt ready for shipment

Salt Factory, Colchani on Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Close-up of salt crystals and processing equipment

Salt Factory, Colchani on Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Piles of raw salt awaiting processing in the factory

Salt Factory, Colchani on Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Interior view showing salt bags and processing area

The factory also had a display of local mineral rocks, including Pyrite (FeS2), aka "fool's gold." You could buy plastic-wrapped chunks, little bags of Salar salt, and hand-sculpted salt figurines. It was the world's most mineral-rich gift shop.

Volcanic Mineral Rock, Salt Factory, Colchani on Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Display of pyrite (fool's gold) and other local minerals

Volcanic Mineral Rock, Salt Factory, Colchani on Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Close-up of mineral specimens including pyrite crystals

Volcanic Mineral Rock, Salt Factory, Colchani on Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Various volcanic rocks and minerals on display

Beyond the factory, Colchani boasts a Salt Museum and shops selling gorgeous, authentic llama and alpaca wool gear, hats, and handicrafts. I went full-on local and bought a llama wool poncho and a traditional hat, which I wore for the rest of the trip like a proud, slightly itchy, tourist. My wife picked up some delicate salt sculptures, which survived the journey home with the fragility of grenades.

Salt Museum, Colchani, Bolivia: Exterior of the salt museum building made of salt bricks

Salt flats landscape near Colchani, Bolivia: Expansive view of the Salar with distant mountains

Cultural & Social Context: Life on the Salar's Edge Life in villages like Colchani is a masterclass in adaptation. The Quechua communities here have a symbiotic relationship with the Salar. They don't just extract salt; they understand its rhythms - the dry season for harvesting, the wet season when the flat becomes a mirror and tourism shifts. Their economy is a three-legged stool: traditional salt gathering, burgeoning lithium industry jobs (though this brings complex issues of foreign investment and environmental impact), and tourism. The handicrafts - woven textiles, salt sculptures - are not just souvenirs but a continuation of artistic traditions and an important income stream. Eating in a local diner made of salt bricks isn't just a novelty; it's participating in an economy that has creatively turned its primary challenge (isolation, a harsh environment) into its unique selling point.

Llama wool poncho and traditional Bolivian hat purchased in Colchani: Traditional textiles bought as souvenirs

Before leaving, we had a fantastic lunch at a local salt-brick diner next to the museum. The food was hearty and delicious, a testament to the fact that Bolivian cuisine can make anything taste good, even when you're sitting in a building you're technically seasoning just by being there.

Local salt-brick diner next to the Salt Museum in Colchani: Traditional restaurant made of salt blocks

A street dog resting in Colchani village: Local canine resident relaxing in the sun

What really is the Salar de Uyuni?

According to National Geographic, "Bolivia's Salar de Uyuni is considered one of the most extreme and remarkable vistas in all of South America, if not Earth. Stretching more than 4,050 square miles of the Altiplano, it is the world's largest salt flat, left behind by prehistoric lakes evaporated long ago. Here, a thick crust of salt extends to the horizon, covered by quilted, polygonal patterns of salt rising from the ground.

At certain times of the year, nearby lakes overflow and a thin layer of water transforms the flats into a stunning reflection of the sky. This beautiful and otherworldly terrain serves as a lucrative extraction site for salt and lithium - the element responsible for powering laptops, smart phones, and electric cars. In addition to local workers who harvest these minerals, the landscape is home to the world's first salt hotel and populated by road-tripping tourists. The harsh beauty and desolateness of Salar de Uyuni can make for an incredible experience or a logistical nightmare."

Discovery Channel says, "Salar de Uyuni is the World's Largest Natural Mirror."

"It is so boundless and bright white that Neil Armstrong is said to have mistaken it for an enormous glacier seen from space," adds China Global Television Network.

So, in short, it's a giant, reflective, lithium-filled, astronaut-confusing, salt-crusted pancake. And it's magnificent.

The Star Wars Connection

Pop Culture & Mythology Infusion: A Galaxy Far, Far Away... in Bolivia Yes, you read that right. The stark, white and red landscape of the salt flat was the perfect stand-in for the mineral planet Crait in Star Wars: The Last Jedi (Episode VIII). The official databank describes Crait as an abandoned Rebel base, a mining installation turned fortress. It's poetic, really. The Salar, a place of real mineral extraction and extreme isolation, playing the role of a hidden rebel outpost in a fictional galaxy. It adds a layer of modern myth to an already ancient landscape. Beyond Star Wars, the Salar features in other films and countless documentaries, its otherworldliness making it a go-to for directors needing "not of this Earth" scenery. It's a place where reality is so strange, it passes for science fiction.

The Salar de Uyuni was the shooting location for Crait.

Star Wars scene filmed on the Salar de Uyuni salt flats: The red and white landscape of Crait from Episode VIII

Volcán Thunupa (Tunupa Volcano) and Mummies of Coqueza

15:30

Geographical & Mythological Deep Dive: The Sleeping Giant Towering over the northern edge of the Salar at 17,457 feet is the dormant volcano Tunupa. This isn't just a pretty backdrop; it's a central figure in local mythology. One legend says Tunupa was a beautiful, powerful woman (or a god, depending on the version) who wept tears of milk after being wronged, creating the salt flat. Another says the mountain is a protective deity. Its slopes created an "island" in the salt desert, where villages like Coqueza (population: fewer than 70 incredibly tough people) cling to existence at 12,103 feet. For the ancient Aymara and later cultures, volcanoes were not just geological features; they were Apus - sacred mountain spirits, sources of water, life, and divine power. Tunupa's presence dominates the landscape physically and spiritually.

After lunch, we drove straight onto the Salar toward Tunupa. We hit the jackpot: an area of shallow standing water, turning the flats into the famous sky-mirror. It was like driving on the clouds.

Reflective water on the Salar de Uyuni salt flats: Mirror-like surface creating perfect sky reflections

Tunupa Volcano island emerging from the salt flats: The volcano rising from the Salar with reflective water in foreground

We reached the island with the colossal, snow-dusted crater of Tunupa looming over us. It was humbling, like being judged by a silent, ancient god made of rock and ice.

View of the (snow-capped in winter) Tunupa Volcano from the island: Majestic volcano dominating the landscape

Next to the crater was a stunning Rainbow Mountain, its stripes of mineral-rich hues looking like a painter went wild on the slope. Nature's abstract art at 16,000 feet.

Colorful Rainbow Mountain adjacent to Tunupa Volcano: Striated mineral deposits creating a rainbow effect on the mountainside

In Coqueza, we bought tickets from the community tourism association (a gatekeeper in the literal sense) for the hike to Las momias de coqueza.

Llamas and alpacas at entrance to Coqueza village on the salt flat island: Small settlement at the base of Tunupa Volcano

View of the Salar from Coqueza village: Panoramic vista of the salt flat from the village

Traditional buildings in Coqueza made of salt bricks: Village structures constructed from local salt blocks

Rainbow Mountain and Tunupa Volcano as seen from Coqueza: Colorful mountain slopes with the volcano in background

Tourist service provider office and gate in Coqueza: Entry point for tours to the mummy caves

We drove up to the trailhead. The landscape was barren, epic, and empty. Signs for zip lines and hot air balloons stood like lonely sentinels of a pre-pandemic tourism boom.

Barren landscape leading to the mummy cave trailhead: Rocky, desolate terrain near Coqueza

Deserted activity signs near Coqueza village: Signs for zip lines and balloon rides in the empty landscape

The hike up was short but steep. We passed towering Trichocereus giant cactus, ancient survivors in a land of rock and salt.

Giant Trichocereus cacti on the hike to the mummy cave: Ancient cacti growing in the rocky landscape

Close-up of a giant cactus near the trail: Detailed view of the Trichocereus cactus spines and texture

Rocky path leading up to the cave entrance: Steep trail through volcanic rock formations

View of the salt flats from the ascending trail: Panoramic vista of the Salar from the hillside

Approaching the cave entrance on the hillside: View of the cave opening in the rocky slope

Rock formations near the Cave of the Mummies: Volcanic rock structures surrounding the cave

Entrance to the Cave of the Mummies at Coqueza: The dark opening of the ancient burial cave

View from inside the cave entrance looking out: Perspective from within the cave showing the outside landscape

Interior rock wall of the cave: Textured volcanic rock inside the cave chamber

Las momias de Coqueza: the mummies of Coqueza (The Cave of the Mummies)

Grocery of the Mums of Coqueza

17:30 PM

Informational sign titled 'Grocery of the Mums of Coqueza' at the cave entrance: Educational sign explaining the mummy cave

The sign at the entrance, hilariously titled "Grocery of the Mums of Coqueza," explained that these are ancient burials (chullpares) of important figures from the Lordship of the Greater Land of Los Lipez. Our guide, Juan, explained that "grocery of the mums" refers to the Aymara and Inca tradition of sharing meals with mummified ancestors and leaving them food and gifts - a practice that views death not as an end, but as a continuation of community. It's a perspective that's both haunting and beautiful.

Historical & Cultural Deep Dive: The Andean Relationship with Death The mummies of Coqueza are a profound window into Andean cosmology. Ancient civilizations here were practicing mummification at least 2,000 years before the Egyptians got famous for it. For the Aymara, Tiwanaku, and Inca cultures, death was not a separation. The deceased, especially important ancestors, remained active members of the community - mallquis. They were consulted, fed, given drink (including chicha, corn beer), and included in celebrations. Their mummified bodies were kept in above-ground tombs or caves (chullpas) like this one. The Spanish conquest brutally disrupted this, desecrating tombs in search of gold and scattering bones. The fact that this cave remained undisturbed is a minor miracle. Being here isn't just looking at old bodies; it's encountering a fundamentally different, more integrated philosophy of life, death, and time.

We entered the cave. A sliver of light pierced through a grilled hole, and a curious chinchilla peered in at us. The atmosphere was immediately heavy, silent, and profoundly peaceful.

Light filtering into the cave through a grilled opening: Sunlight entering the dark cave interior

Inside rock-cut chambers were the mummified remains of six individuals, curled in the fetal position, wrapped in straw, leaves, and textiles. They had been here, untouched, for over 500 years. Their hair, clothing, and peaceful poses were preserved. There was no smell of decay, just the musty scent of ancient stone and dry earth.

One of the mummified individuals in a fetal position inside a rock chamber: Ancient mummy preserved in a natural cave tomb

It wasn't scary or morbid. It was calm, almost meditative. You felt a connection to deep time, to the cycle of everything. It was sad, tranquil, and strangely hopeful, all at once.

Another mummy in a side chamber of the cave: Additional mummified remains in a separate rock niche

Close-up view of a mummy's preserved hair and wrappings: Detailed look at the ancient textiles and hair preservation

Mummy surrounded by ceramic offerings inside the chamber: Ancient pottery left as offerings with the mummified remains

One chamber held a woman and two children. Seeing the little ones was heart-wrenching. What story ended here, 500 years ago?

Chamber containing the mummies of a woman and two children: Family group burial in the cave

Surrounding the mummies were earthen jars, plates, and bowls. On the floor in front of them, people had left modern offerings: wine, food, coins, and even cigarettes. In this cave, the past isn't locked away; it's invited for a smoke and a drink.

Offerings of food, wine, and money left for the mummified ancestors: Modern offerings placed in the ancient burial cave

Sunset over Salar de Uyuni

18:12

We wished peace to the ancient souls in the cave, said goodbye to the brooding Tunupa, and headed back across the Salar towards Uyuni. Our guide, Nelson, found another patch of shallow water for photos. I attempted some hilarious "extreme perspective" shots, making my wife stand on my hat and my son on my shoulder. The results were less "artistic masterpiece" and more "family with a poor grasp of physics." But sunset? Sunset on the Salar was pure, unfiltered magic. The sky exploded in colors that reflected perfectly on the watery mirror, turning the world into a kaleidoscope of fire and gold.

Panoramic view of the Salar de Uyuni at sunset: Wide vista of the salt flat during golden hour

Sunset colors reflecting on the shallow water of the salt flats: Vibrant sky colors mirrored in the water on the Salar

Silhouette against the sunset on Salar de Uyuni: Human figure against the dramatic sunset sky

Golden hour light on the expansive salt flat: Warm sunset light bathing the Salar's surface

Deep orange sky as the sun sets over the Salar: Intense orange sunset colors over the salt flat

Last light of day on the salt crust patterns: Final sunlight illuminating the polygonal salt formations

Twilight over the Salar de Uyuni: Blue hour after sunset on the salt flats

We wrapped up the day with a delicious Bolivian dinner in Uyuni, picked up supplies for our upcoming off-road odyssey, and returned to our salty palace, ready to collapse. The next few days, we were promised, would be unforgettable. They had no idea.

Huge Natural Crystalline Patterns on Salt Crust

The salt flat isn't just flat. It's covered in massive, naturally-forming polygonal patterns, like a giant honeycomb or cracked mud, but made of salt. These formations can be big enough to park a couple of 4x4s inside. They're created by the repeated cycles of flooding and evaporation, a slow-motion geologic art project.

Large natural polygonal salt formations on the Salar: Geometric salt crust patterns created by evaporation

Close-up of the intricate crystalline salt patterns: Detailed view of the salt crystallization patterns

December 29, 2022

8:30 AM

A country in turmoil

Protests Turn Violent in Bolivia Amid a Political Crisis

Ah, travel. Just when you think you've got it figured out, a country decides to have a political meltdown. We were supposed to be picked up at 8:30 AM, but our guide Nelson called: there was a gasoline shortage because protesters in Santa Cruz were burning cars and clashing with police after the arrest of a governor. You know, normal Tuesday stuff. Having just escaped similar chaos in Peru, we briefly considered bailing to Chile. But the part of Bolivia we were in felt peacefully disconnected from it all. We decided to roll the dice. Spoiler: best decision ever.

9:30 AM

The folks at Expediciones Mammut worked miracles, found gas, and sent their Japanese colleague Masayuki-san in a Toyota Tundra to get us. He didn't even bother with roads, just charged diagonally across the terrain and hopped onto the highway like it was a mild suggestion. We were taken to their office in Uyuni to sort out logistics, which gave us time to explore the town center.

Driving across open terrain near Uyuni: Toyota Tundra driving off-road to reach us during the fuel crisis

Historical Context: Bolivia's Political Landscape Bolivia's history is a complex tapestry of indigenous civilizations, brutal Spanish colonization, a struggle for independence, and persistent political instability. The tensions often center on the distribution of wealth from natural resources (like gas and lithium), regional autonomy (the lowland department of Santa Cruz vs. the highland government in La Paz), and the rights of the indigenous majority. The 2019 political crisis, the 2020 elections, and the 2022 protests we encountered are all chapters in this ongoing story. Traveling here requires an understanding that you're in a living, breathing nation working through deep-seated challenges, not just a picturesque backdrop. The resilience and warmth of the Bolivian people in the face of this uncertainty is perhaps the most impressive sight of all.

Luz at the Expediciones Mammut office in Uyuni: Staff member helping to arrange our tour during the political crisis

Interior of the Expediciones Mammut office: Tour company office with maps and travel information

Tour maps and information at the Mammut office: Wall maps showing tour routes across the Salar and Altiplano

Additional office space and seating area: Waiting area in the tour company office

Storage and equipment area in the office: Gear storage for tours and expeditions

View of the office entrance and waiting area: Front area of the Expediciones Mammut office

Exterior of the Expediciones Mammut office building: Building facade of the tour company in Uyuni

We wandered down the main street and found a bustling marketplace next to a military regiment. It was a riot of colors, smells, and sounds - vendors selling everything from Bluetooth speakers to fresh fish. I bought peanuts because when in doubt, snack.

Busy street scene in Uyuni near the marketplace: Vibrant market area in the town center

Inside the bustling marketplace of Uyuni: Interior view of the market with various stalls

Stalls selling vegetables and fruits at the Uyuni market: Fresh produce vendors in the local market

Soon, the call came. Logistics were sorted. We jumped into Nelson's Nissan Patrol and set off for our first official day of off-roading.

Bolivia's Train Cemetery: The Great Train Graveyard at Uyuni

11:21 AM

Historical Deep Dive: Rails to Rust The Train Cemetery is a monument to boom, bust, and geopolitical drama. In the late 19th century, Bolivia had big dreams of being a mineral export powerhouse. British engineers built railroads to connect the mines of the Altiplano to the Pacific port of Antofagasta. President Aniceto Arce inaugurated the line to Uyuni in 1890 with great fanfare. But then came the War of the Pacific (1879-1884), where Bolivia and Peru lost to Chile. Bolivia lost its coastline and Antofagasta. Suddenly, the railroad was a line to nowhere. The trains, mostly British-built steam locomotives, were abandoned where they stood. The salt air accelerated their decay into the surreal, rusting sculptures you see today. It's a poignant place: a testament to ambition, the cruel turns of history, and the relentless power of nature to reclaim human endeavors.

This place is seriously weird. It's a sprawling junkyard of rusting steam locomotives and rail cars from the late 1800s, slowly being consumed by the salt and wind. It's like a post-apocalyptic playground or a heavy metal album cover come to life. The story is sad: Bolivia built this railroad for mineral exports, then lost its coastline to Chile in the War of the Pacific, rendering the trains useless. Now they're a wildly popular tourist attraction. Irony, thy name is rust.

Train Cemetery - The Great Train Graveyard, Uyuni, Bolivia: Rusting steam locomotive abandoned in the salt desert

Train Cemetery - The Great Train Graveyard, Uyuni, Bolivia: Another angle of the decaying train remains

Train Cemetery - The Great Train Graveyard, Uyuni, Bolivia: Close-up of rusted train wheels and undercarriage

Train Cemetery - The Great Train Graveyard, Uyuni, Bolivia: Panoramic view of the Train Cemetery under blue skies

Train Cemetery - The Great Train Graveyard, Uyuni, Bolivia: Rows of abandoned train cars stretching into the distance

Train Cemetery - The Great Train Graveyard, Uyuni, Bolivia: Detail of a rusted train car with missing panels

Train Cemetery - The Great Train Graveyard, Uyuni, Bolivia: Tourists exploring the Train Cemetery

Train Cemetery - The Great Train Graveyard, Uyuni, Bolivia: Wide shot of the vast train graveyard landscape

Train Cemetery - The Great Train Graveyard, Uyuni, Bolivia: Decaying locomotive engine amidst the salt flat

Train Cemetery - The Great Train Graveyard, Uyuni, Bolivia: Rusted train car interior with graffiti

Return to Salar de Uyuni

From the graveyard of the past, we returned to the blinding white present of the Salar. This was it: the start of our three-day off-road adventure across the roof of the Andes.

Nissan Patrol - 4x4 offroad tour of Salar de Uyuni and Bolivian Andes Altiplano: Our tour vehicle ready for adventure

Ojos de Agua - Eyes of Water

12:43 PM

Geological Phenomenon: The Salar's Cold Springs The Ojos de Agua are fascinating geothermal... well, cryothermal features. Mineral-rich water, flowing in underground channels beneath the massive salt crust, finds weak spots to escape. The pressure release causes it to bubble up to the surface like a cold spring. They look like little volcanic mud pots but are just chilly. The strong metallic smell on your hands after touching the water is a direct sniff of the Salar's rich interior cocktail of lithium, magnesium, and other dissolved minerals. It's a reminder that this vast, solid-looking plain is dynamic, with hidden aquatic life beneath its feet-thick skin.

In the middle of this vast, solid-looking desert, there are random bubbling pools of water. They're called Ojos de Agua - Eyes of Water - and they're formed by mineral-rich water escaping from beneath the salt crust. They bubble away like tiny, cold Jacuzzis built by geology. We dipped our hands in, and they came out smelling strongly of metal, like we'd been fondling old pennies. The Salar was literally letting us smell its minerals. How considerate.

Ojos de Agua - Eyes of Water, Salar de Uyuni: Bubbling mineral pool known as an 'Ojo de Agua' on the salt flat

Ojos de Agua - Eyes of Water, Salar de Uyuni: Close-up of the bubbling water escaping the salt crust

Ojos de Agua - Eyes of Water, Salar de Uyuni: Multiple bubbling pools dotting the salt flat

Ojos de Agua - Eyes of Water, Salar de Uyuni: Panoramic view of the Ojos de Agua area

Ojos de Agua - Eyes of Water, Salar de Uyuni: Standing next to one of the bubbling mineral pools

Monumento al Dakar: Dakar Monument

12:56 PM

The Dakar Monument on the salt flats: Salt sculpture commemorating the Dakar Rally stage

In 2015, the infamous Dakar Rally routed its eighth stage right across the Salar de Uyuni to Iquique, Chile. The drivers flagged off here on Jan. 11, 2015, probably wondering why they were racing across a giant salt shaker at 12,000 feet. To commemorate this feat of vehicular madness, there's a monument made of salt. Because of course there is.

Dakar Monument: Monumento al Dakar, Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia, 29-DEC-2022: Close-up of the Dakar Monument salt sculpture

Behind the monument is the old, abandoned Hotel de Sal Playa Blanca. Inside, two salt pillars are plastered with stickers from high-performance automotive brands, left by rally teams and fans. It's like a shrine to speed, built out of the slowest-forming material on Earth.

Dakar Memorial, Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Salt pillars covered in automotive stickers inside the old hotel

Dakar Memorial, Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Close-up of stickers on the salt pillar

Dakar Memorial, Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Another view of the sticker-covered salt structures

Plaza de las Banderas: Flag Square

12:59 PM

Near the Dakar monument is a raised salt platform called the Plaza de las Banderas - Flag Square. Dozens of national flags fly from poles, often several to a pole. It's a tradition for visitors to place their country's flag here. We saw Old Glory flying proudly (at least twice), and it was incredibly moving to see the blue and yellow of Ukraine sharing a pole with Venezuela and Panama. In the middle of the Bolivian desert, a symbol of defiance and courage fluttered in the thin, high-altitude wind.

The Flag Square (Plaza de las Banderas) on the salt flats: Collection of national flags on the Salar

Plaza de las Banderas: Flag Square at Salar de Uyuni: Flags of many nations flying at the Flag Square

Plaza de las Banderas: Flag Square at Salar de Uyuni: Ukrainian flag flying alongside others at the Flag Square

Plaza de las Banderas: Flag Square at Salar de Uyuni: Another view showing multiple national flags

Hotel de Sal Playa Blanca, Salar de Uyuni

The original old abandoned Hotel Palacio de Sal

13:07

Historic photo of the original Hotel Palacio de Sal: Early salt hotel that pioneered salt-block construction

This is the OG salt hotel, built in the mid-1990s. It had 12 double rooms and a shared bathroom with no shower. The influx of tourists overwhelmed its primitive sewage system, causing an environmental mess. It was shut down in 2002. Now called Hotel de Sal Playa Blanca, it's used as a lunch stop. We ate here, surrounded by the impressive, slightly crumbling, salt sculptures of a bygone tourism era. A newer hotel with the same name exists elsewhere, because nothing can be simple.

Hotel de Sal Playa Blanca, Salar de Uyuni: The Old Hotel Palacio de Sal: Exterior of the abandoned hotel

Hotel de Sal Playa Blanca, Salar de Uyuni: The Old Hotel Palacio de Sal: Interior salt sculpture in the old hotel

Hotel de Sal Playa Blanca, Salar de Uyuni: The Old Hotel Palacio de Sal: Salt block walls and architectural details inside the hotel

Stuck on the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats

14:20

And now, the main event. The Salar, for all its beauty, is a sneaky, treacherous beast. The salt crust can be deceptively thin. Our trusty Nissan Patrol found one of those weak spots. With a sickening crunch, it broke through into the soft, wet, sludgy mud beneath. We were stuck. Properly, hilariously, epically stuck.

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: The Nissan Patrol stuck in the soft mud beneath the salt crust

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: View of the stuck vehicle from a distance

Nelson tried valiantly to free it. No dice. He climbed on the roof, got a bar of signal, and called the office. We relaxed on the salt, turning our vehicular crisis into a bizarre picnic.

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Waiting for rescue while sitting on the salt crust

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Another view of the stuck vehicle and surrounding salt flat

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Wide shot showing the vehicle's position on the salt flat

14:49

Help arrived! Masayuki-san and Luz in the Toyota Tundra. The Tundra promptly also broke through the crust and got stuck. We now had two vehicles immobilized. They had tools - wooden poles, blocks, jacks - and attempted a heroic rescue. The Patrol got out briefly, then immediately sank again. It was like watching a nature documentary where the prey almost escapes.

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Attempting to free the stuck vehicle with recovery equipment

15:20

A third vehicle, a Toyota Land Cruiser, appeared on the horizon like a heroic mirage. It drove toward us... and also crashed through the crust, wheels deep in slush. Three vehicles. Stuck. It was a comedy of errors written by the Salar itself.

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Third vehicle stuck while attempting rescue

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Panoramic view of the three stuck vehicles

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Close-up of the recovery attempt with multiple vehicles

Luz spotted a distant motorcycle andwith me in tow waving like a maniac, flagged down the biker. After a quick chat, she hopped on and they sped off toward Uyuni to get more help. We were living in an adventure movie.

17:10

A solid patch of salt crust was identified some distance away. Our luggage, gas cans, and essentials were hauled over and placed on a tarp. Our bags looked so lonely and small in the infinite white.

Luggage on the Salt Flats: Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Our luggage placed on a tarp on the salt flat

Luggage on the Salt Flats: Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Another view of our isolated luggage on the Salar

Finally, a tow truck arrived on the horizon. The cavalry! It began the delicate operation of extracting three very embarrassed 4x4s.

Luggage on the Salt Flats: Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Tow truck arriving for the recovery operation

Tow Truck on Salt Flats to Rescue Vehicles Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Tow truck preparing to extract the stuck vehicles

Tow Truck on Salt Flats to Rescue Vehicles Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Recovery operation in progress

Not long after, our savior arrived: a fourth Toyota Land Cruiser. It reached us without sinking. We piled in with our salvaged luggage, breathed a collective sigh of relief, and were back on our way. The Mammut team later confirmed everyone and every vehicle was fine. What was supposed to be a simple drive turned into an epic, unscheduled, and utterly memorable Salar adventure.

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Final rescue vehicle arriving to transport us

Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: View of the recovery operation from a distance

Luggage on the Salt Flats: Stuck in the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats, Bolivia: Loading our luggage into the rescue vehicle

Funny Pictures at Salar de Uyuni: Extreme Perspective Photos

The Salar is world-famous for forced-perspective photos that play with the featureless horizon. I'd tried some clumsy ones, but Nelson, a master of the art, took these gems. Behold: my wife standing on my hat, my son towering over me, and general family silliness on the world's largest blank canvas.

Funny Pictures at Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Extreme Perspective Photography: Forced perspective shot making a person appear giant

Funny Pictures at Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Extreme Perspective Photography: Another creative perspective shot on the salt flat

Funny Pictures at Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Extreme Perspective Photography: Vertical perspective shot with dramatic scale effects

Funny Pictures at Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Extreme Perspective Photography: Family posing with perspective tricks on the Salar

Isla Incahuasi: The "House of the Incas" Island

18:20

Panorama of Salar de Uyuni from top of Incahuasi Island

Ecological & Historical Oasis: Incahuasi Island Rising from the center of the Salar, Incahuasi is a hilly, rocky island formed by the top of an ancient volcano. It's a crucial ecological island in a literal sea of salt. The most striking residents are the forests of giant Trichocereus bridgesii cactus, some over 700 years old and reaching 33 feet. They grow agonizingly slowly, about 1 cm per year in this harsh environment. The island also has fossilized coral and algae, proving that this was once a lake or sea floor. For the Incas, it was a vital rest stop (tambo) on the trade routes across the Altiplano, offering shelter, a vantage point, and possibly freshwater springs. It's a place where geology, ecology, and human history intersect on a grand scale.

Incahuasi Island is a volcanic pimple in the middle of the Salar. A trail leads to its 12,539-foot summit, offering a 360-degree view that will make your jaw drop and your lungs complain. The island was a pit stop for Inca traders - a place to rest their llamas and probably complain about the lack of decent snacks. The presence of corals and seashells here is a mind-bender, screaming that all this was once underwater.

Incahuasi Island, Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: View of the island rising from the salt flat

The island is also home to a forest of giant, 700-year-old cacti, standing like silent, spiky sentinels. They're the Trichocereus bridgesii, or Bolivian torch, and they are magnificent.

Incahuasi Island, Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Giant cacti forest on the island

Incahuasi Island, Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Close-up of ancient giant cacti on the island

Incahuasi Island, Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: Hiking trail through the cactus forest on the island

Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina

20:00

We spent the night at the Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, located on Tambo Loma island just off the Salar's south shore. This hotel is built in the shape of the ancient Andean Chakana (Inca Cross), a symbol representing the three worlds (underworld, this world, upper world) and the Southern Cross constellation. It was a beautiful, quiet place to rest, with walls made of salt and local volcanic stone that stored the day's heat for the cold night.

Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: Exterior of the hotel shaped like an Inca cross

Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: Interior courtyard of the hotel

Salar de Uyuni and Tambo Loma Island - Andes Altiplano Desert - Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: View of the Salar from the hotel location

Chakana shaped Hotel in the Andes Altiplano: Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: Aerial view showing the Inca cross design of the hotel

Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: Interior hallway with salt-block construction

Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: Guest room with salt-block walls and traditional decor

Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: Another view of the hotel interior showing salt architecture

Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: Dining area with salt-block walls and panoramic windows

Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: Lounge area with comfortable seating and salt-block architecture

Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: View from the hotel showing the surrounding landscape

Hotel de Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: Another interior view showing the hotel's unique architecture

Hotel De Sal Luna Salada, Uyuni, Bolivia: The Hotel Made of Salt - Lounge area with expansive windows overlooking the Salar

Hotel De Sal Cruz Andina, Tambo Loma, Colcha K, Potosí, Bolivia: View of the hotel's exterior showing its cross-shaped design

December 30, 2022

We packed up, ate breakfast, and hit the road, leaving the Salar behind. Our mission now: to drive across the sacred, barren, breathtaking Andes altiplano towards Chile.

Julaca, Bolivia (20.9112° S, 67.5649° W, alt. 12,500 feet)

10:48 AM

Julaca, Bolivia: Panoramic view of the tiny altiplano village

Our first stop was the tiny, windswept hamlet of Julaca. It consisted of a few adobe and salt-brick buildings on the roadside, rail tracks stretching toward Chile, and a bizarre metal-wire-mesh sculpture of an Alien from the movie franchise. Because why not?

Rail Track for Railway Trains to Chile at Julaca, Bolivia: Railroad tracks leading toward Chile across the altiplano

Julaca, Bolivia: View of the village with traditional buildings

Julaca, Bolivia: Another view of the remote altiplano settlement

Julaca, Bolivia: Traditional adobe and salt-brick structures in the village

The "Julaca Salt Shop" was a tiny, surreal minimarket in a salt-brick building, stocked with a weird mix of local goods and random Americana: Snickers, Lays, Skittles, Pringles, Corona. With no other customers, I bought a couple of blue energy drinks from the lonely shopkeeper. It felt like supporting the most remote convenience store on Earth.

Alien Sculpture at Julaca, Bolivia: Wire-mesh sculpture of the Alien movie creature in the remote village

Alien Sculpture at Julaca, Bolivia: Another view of the surreal Alien sculpture against the altiplano landscape

Grocery / Minimarket Store at Julaca, Bolivia: Small salt-brick shop in the remote village

Grocery / Minimarket Store at Julaca, Bolivia: Interior of the small village shop

Grocery / Minimarket Store at Julaca, Bolivia: Shelves stocked with goods in the remote shop

Grocery / Minimarket Store at Julaca, Bolivia: Shopkeeper in the small village store

Grocery / Minimarket Store at Julaca, Bolivia: Another view of the shop interior showing various products

Estancia Chakha: Wildlife Valley and Flat Tire

12:03 PM

Wildlife Valley on Andes Altiplano at Estancia Chakha, Bolivia: Panoramic view of the green valley with grazing animals

We turned south on a dirt track toward the hamlet of Alota. Just before Estancia Chakha, we passed a stunning green valley teeming with wildlife: herds of alpaca, llama, and guanaco grazing peacefully. It was a lush oasis in the rocky altiplano. And then, as if to remind us this was a real adventure, we got a flat tire. Nelson swapped it with the spare in minutes, a true professional.

Wildlife Valley on Andes Altiplano at Estancia Chakha, Bolivia: Herds of alpacas and llamas grazing in the valley

Wildlife Valley on Andes Altiplano at Estancia Chakha, Bolivia: Close-up of alpacas in the green valley

Flat Tire on Andes Altiplano at Estancia Chakha, Bolivia: Changing a flat tire on the remote altiplano road

Flat Tire on Andes Altiplano at Estancia Chakha, Bolivia: Close-up of the tire change in progress

Villa Alota

12:27 PM

We reached the small village of Villa Alota and stopped for lunch at the Hospedaje Fatima, a simple roadside diner. It was here we had one of the most fascinating encounters of the trip.

Villa Alota, Potosi, Bolivia: View of the small altiplano village

Villa Alota, Potosi, Bolivia: Traditional buildings in the village

Restaurant Hospedaje Fatima, Route 701, Villa Alota, Potosi, Bolivia: Simple roadside diner where we had lunch

Restaurant Hospedaje Fatima, Route 701, Villa Alota, Potosi, Bolivia: Interior of the local restaurant

Restaurant Hospedaje Fatima, Route 701, Villa Alota, Potosi, Bolivia: Dining area of the local eatery

Meeting Adam Palowski - the biker who rides across the world

Parked outside was a motorcycle loaded to the gills with gear, covered in stickers and flags, with EU plates from Poland. This was the bike of Adam Palowski, a man from Poland who is riding his motorcycle across the world. He's been through Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, and was now in the middle of South America. We met him, swapped stories, and took a photo together. In the middle of the Bolivian altiplano, at 12,500 feet, we shared a moment with a modern-day nomad, a reminder of the endless ways to explore this incredible planet.

Adam Palowski's Motorcycle in Villa Alota, Bolivia: Heavily loaded adventure motorcycle with global stickers

Adam Palowski's Motorcycle in Villa Alota, Bolivia: Close-up of the motorcycle's loaded gear and stickers

Adam Palowski's Motorcycle in Villa Alota, Bolivia: Another view of the adventure motorcycle parked outside the restaurant

Adam Palowski and Supratim Sanyal in Villa Alota, Andes Altiplano, Bolivia (South America): Meeting a Polish world traveler in the remote Bolivian altiplano

We chatted a bit and exchanged contact information, promising to look each other up in Poland, Georgia or the United States. Adam is easily among the most remarkable people I have met in my life, a shining example of what travel does to people. Warm, laid back, smiling and brave. He let me sit on his bike. Adam can be found on facebook where he dumps his diary. He went the other way across the Salar to Peru, and had some pretty scary experiences in the chaotic political violence in Peru.

This chance encounter with a fellow traveler in the vastness of the Bolivian highlands is a classic example of the 'camaraderie of the road.' The Altiplano has been a crossing point for millennia, from pre-Columbian llama caravans to Spanish conquistadors and modern adventurers on motorbikes, all drawn by its stark beauty and challenging paths.

Adam Palowski's adventure motorcycle in Villa Alota, Bolivia, showcasing a BMW GS model equipped for long-distance travel across the rugged Altiplano terrain at approximately 12,000 feet elevation

This image sequence captures different perspectives of Adam Palowski's adventure motorcycle setup in Villa Alota. The first image provides a broader view of the bike in its highland environment, while the table-wrapped image offers a closer examination of specific equipment and details, illustrating how travelers prepare their vehicles for the extreme conditions of the Bolivian Altiplano.

|

| Detailed view of Adam Palowski's adventure motorcycle in Villa Alota, Bolivia, showing specialized gear and luggage systems for transcontinental travel (table-wrapped image for detailed examination) |

Lunch break over, we got out of Villa Alota back on Route 701 driving west towards Avaroa to greet Volcán Ollagüe.

Route 701 cuts across the southwestern Potosí Department, a region historically defined by silver mining that bankrolled the Spanish Empire. The road itself is a modern scratch on an ancient landscape, following paths first worn by indigenous Aymara and Quechua peoples traveling between settlements and salt flats.

Westbound Bolivia Route 701 from Villa Alota towards Avaroa with Volcán Ollagüe visible in the distance, showcasing the remote gravel roads that connect highland settlements across the Altiplano at approximately 13,000 feet elevation

Volcán Ollagüe

14:10 PM

Panoramic view of Volcán Ollagüe (Volcano Ollague) on the Bolivia-Chile border, showing the massive 19,252-foot andesite stratovolcano with its characteristic fumarolic activity emitting steam and gases over 300 feet into the air

We get off gravel track Route 701 to a dirt track going south towards Laguna Colorada. There is a great viewpoint (map) at 14,421 feet on this dirt track from which the massive 19,252 foot andesite stratovolcano Volcán Ollagüe can be seen looming behind at the boundary of Bolivia and Chile.

Volcán Ollagüe is part of the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes, a line of fire created by the subduction of the Nazca Plate under the South American Plate. Its name likely derives from the Aymara words 'ulla' (penis) and 'ghawi' (mountain), though its exact meaning is debated. For local communities, such volcanoes are often considered Apus (mountain spirits), deities that govern weather and fertility and demand respect.

Volcano Ollagüe continues to emit steam and volcanic gases over 300 feet into the air. The "Fumarolic activity" indicates it can wake up to cause trouble any time.

The constant plume of gas is a sign of a restless magma chamber below. The volcano's last confirmed eruption was over 10,000 years ago, but the persistent fumaroles suggest it is merely dormant, not extinct. In local folklore, such steaming vents are sometimes seen as the breath of the mountain spirit or portals to the underworld.

Mirador (Viewpoint) of Volcán Ollagüe (Volcano Ollague), Bolivia, showing the visitor observation area at 14,421 feet elevation with interpretive signage and panoramic views of the volcanic landscape

These consecutive images of Volcán Ollagüe provide complementary perspectives on this significant Andean volcano. The first wide-angle view shows the full scale of the mountain in its geographical context, while the second image focuses on the visitor experience at the designated viewpoint, illustrating how travelers engage with and interpret this dramatic volcanic landscape.

Detailed view from the Volcán Ollagüe viewpoint in Bolivia, highlighting the rugged volcanic terrain and atmospheric conditions typical of the high-altitude Altiplano environment

Laguna Chulluncani

14:27

Panoramic view of Laguna Chulluncani, Potosi, Bolivia, at 16,404 feet elevation in the Andes mountains, showing the salt lake with flamingos and the snow-covered 17,848-foot volcanic summit of Cerro Caquella in the Cordillera Occidental range

At an altitude of 16,404 feet in the Andes mountains, Laguna Chulluncani (map) is the first lake after the great Titicaca that we behold on the legendary Altiplano.

Lake Chulluncani is a salt lake with Flamingos on and around it. The 17,848 foot snow-covered volcanic summit of Cerro Caquella in the Bolivian Andes and Cordillera Occidental ranges looms over it.

The Altiplano is a high plateau formed by the collision of tectonic plates, dotted with endorheic basins (closed drainage basins) that collect mineral-rich runoff from the surrounding mountains. Laguna Chulluncani is one such basin. Its waters support brine shrimp and algae, which in turn attract flamingos. For ancient peoples crossing the Altiplano, these lakes were vital landmarks and sources of salt and other minerals.

Close-up view of Laguna Chulluncani, Potosi, Bolivia, showing the mineral-rich waters and the distinctive coloration created by algae and microorganisms that sustain the flamingo population in this high-altitude ecosystem

This sequence of images from Laguna Chulluncani documents the multi-scale nature of high-altitude lake ecosystems in the Bolivian Altiplano. The panoramic view establishes the geographical context with Cerro Caquella towering above, while the subsequent images progressively zoom in to reveal the lake's specific characteristics, mineral content, and the delicate ecological relationships that define this extreme environment.

Laguna Chulluncani shoreline detail showing mineral deposits and the interface between water and land in this high-altitude salt lake ecosystem of the Bolivian Altiplano

Laguna Chulluncani with Cerro Caquella reflected in the mineral-rich waters, illustrating the dramatic interplay between volcanic peaks and high-altitude lakes that characterizes the Cordillera Occidental landscape

Laguna Chulluncani atmospheric conditions showing cloud formations and light patterns unique to the high-altitude Altiplano environment, where weather systems interact with volcanic topography

Final perspective of Laguna Chulluncani emphasizing the vast scale and isolation of this high-altitude lake system in the Potosí Department of southwestern Bolivia

Laguna Hedionda (Stinking Lake): Suri (Andean Ostrich) and more Guanaco

14:39

The mineral-rich salt lake Laguna Hedionda (map) on the Bolivian Altiplano sits at an altitude of 13,520 feet. Snow-covered peaks of mountains Michincha, Cerro de Caquella, Cerro de Pajonal, Cerro de Tatio, Pabellón and Tocorpuri of Cordillera Occidental range of central Andes overlook it. Pink and white flamingos walk on it. Llamas and alpacas graze on its shore.

Laguna Hedionda literally translates to "Smelly Lake" or "Stinking Lake". The smell is of volcanic gases and sulfur, similar to geothermal areas like Hveravellir (Iceland) or Yellowstone.

The sulfuric scent is a clear sign of ongoing hydrothermal activity beneath the lake bed, where volcanic heat interacts with groundwater and minerals. Historically, such 'stinking' lakes were often avoided by indigenous herders for their animals, but they were known as sources of medicinal minerals and salts.

By Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

Laguna Hedionda (Stinking Lake) in Bolivia, a mineral-rich salt lake known for its sulfuric smell and vibrant flamingo population

As we cross Laguna Hedionda on our way to Laguna Cachi (map), we see two Suri birds (Andean Ostrich) and more Guanaco.

The Suri is an endangered species categorized to be in "critical danger" in Peru and only a few hundred left in Bolivia.

Guanaco are related to camels and evolved for survival in the high deserts of the Altiplano.

The Suri, or Darwin's Rhea, is a flightless bird that has roamed the Altiplano for millions of years. Its drastic decline is due to habitat loss, hunting for its feathers and meat, and egg collection. In Andean cosmology, the Suri sometimes appears in myths as a clever trickster figure. Guanacos are the wild ancestors of the domesticated llama. They were crucial to pre-Columbian societies for wool, meat, and as pack animals. Their ability to survive at high altitudes with little water is a marvel of evolution, with specialized blood cells that carry oxygen efficiently in thin air.

Suri (Andean Ostrich) at Laguna Hedionda, Altiplano, Andes Mountains, Bolivia - this endangered flightless bird, also known as Darwin's Rhea, foraging in its high-altitude habitat where only a few hundred individuals remain in Bolivia

This photographic sequence documents the rare Suri (Andean Ostrich) in its natural habitat at Laguna Hedionda. The images progress from establishing shots showing the bird in its environmental context to closer views that reveal distinctive physical characteristics, collectively illustrating the behavior and appearance of this critically endangered species in the Altiplano ecosystem.

Side profile view of a Suri (Andean Ostrich) at Laguna Hedionda showing the bird's distinctive plumage, long neck, and adaptation to high-altitude conditions in the Bolivian Altiplano

Close-up of Suri (Andean Ostrich) head and neck showing detailed feather structure and facial features of this rare high-altitude bird species at Laguna Hedionda, Bolivia

Suri (Andean Ostrich) in motion at Laguna Hedionda illustrating the bird's locomotion and behavior patterns in the mineral-rich environment of this high-altitude salt lake

The wildlife documentation continues with images of Guanaco, showing how these wild camelid relatives have adapted to the extreme conditions of the Altiplano. While the previous images focused on the endangered Suri, these photographs highlight another key species in the high-altitude ecosystem, demonstrating the biodiversity that persists in these challenging environments despite increasing pressures.

Guanaco at Laguna Hedionda, Altiplano, Andes Mountains, Bolivia - this wild camelid relative of the llama demonstrates adaptations for high-altitude survival including specialized blood cells for oxygen efficiency in thin air

Profile view of Guanaco showing the animal's characteristic posture and fur coloration that provides camouflage and thermal regulation in the extreme temperature variations of the Altiplano

Laguna Cachi

15:11

Laguna Cachi, altitude 14,744 feet (map). Mineral rich salt lake with barren desert and high snow-covered mountains around. Flamingos love it. The volcanic mountains are sites for mining with shafts leading into them. Ores extracted include for Sodium, Cobalt, Halite, Lithium, Boron-Borates, Molybdenum, Tungsten and Arsenic.

This region sits on the "Lithium Triangle," holding over half the world's lithium reserves. The mineral wealth has driven both local economies and international conflicts for centuries. The stark beauty of the flamingos against the industrial backdrop is a striking contrast between fragile ecology and resource extraction.

Panoramic view of Laguna Cachi on the Andes Altiplano, Bolivia, showing the mineral-rich salt lake at 14,744 feet elevation with surrounding volcanic mountains that contain significant lithium, cobalt, and other strategic mineral deposits

This extensive photographic series documents Laguna Cachi from multiple perspectives and scales. The panoramic views establish the lake's geographical context within the mineral-rich Lithium Triangle, while closer images reveal specific ecological features, industrial elements, and the interplay between natural beauty and resource extraction that characterizes this region of the Bolivian Altiplano.

Wide-angle view of Laguna Cachi emphasizing the vast scale of this high-altitude salt lake and its position within the barren desert landscape of the Bolivian Altiplano

Laguna Cachi with flamingos in the foreground, illustrating how these birds thrive in the mineral-rich waters despite the extreme altitude and harsh environmental conditions

Detail view of Laguna Cachi shoreline showing mineral deposits and coloration patterns created by different algae and microorganisms in the saline waters

Laguna Cachi with volcanic mountains in the background, highlighting the geological relationship between the lake basin and surrounding volcanic peaks that contribute minerals to the water

Aerial perspective of Laguna Cachi showing the lake's full extent and its relationship to surrounding desert terrain and distant mountain ranges

Laguna Kara

15:54

Transition view between Laguna Cachi and Laguna Kara on the Bolivian Altiplano, showing the continuity of high-altitude lake systems in this desert landscape at approximately 14,800 feet elevation

Leguna Kara (map) sits at an altitude of 14,846 feet in the desert highlands of Bolivian Altiplano nestling under snow-covered peaks of Cordillera Occidental range of central Andes. Flamingos walk on it. The landscape around it gets even more rugged and desert-like than the lakes on our way here. Desierto de Siloli lies ahead.

The Cordillera Occidental is a volcanic range marking the border between Bolivia and Chile. Its peaks, often over 19,000 feet, were formed by the subduction of the Pacific oceanic plate. The snowmelt from these peaks is the primary source of water for the altiplano's lakes, though much of it is lost to evaporation in the arid climate, leaving behind concentrated salts and minerals.

Laguna Kara at 14,846 feet elevation in the Bolivian Altiplano, showing flamingos feeding in the mineral-rich waters with the snow-covered peaks of the Cordillera Occidental range forming a dramatic backdrop

This sequence continues the documentation of high-altitude lakes with images of Laguna Kara, located even deeper into the desert highlands. The photographs show the progression from transitional landscapes to focused views of this specific lake, illustrating how each water body in the Altiplano chain has unique characteristics while sharing common ecological patterns shaped by extreme altitude and aridity.

Detailed view of Laguna Kara shoreline showing mineral crystallization patterns and the interface between water and desert terrain characteristic of these high-altitude saline lakes

Laguna Kara with distant volcanic peaks illustrating the hydrological relationship between mountain snowmelt and lake formation in the closed basin system of the Altiplano

Final perspective of Laguna Kara showing the increasing aridity and ruggedness of the landscape as the journey approaches the hyper-arid Desierto de Siloli

Desierto de Siloli

16:38

Legend has it the high desert of Desierto Siloli (map) is where the earth meets the sky. (Ref: dangerousroads)

At an altitude of 15,604 feet, the Siloli Desert in the Bolivian Altiplano is lined on two sides by colorful volcanic mountains of Cordillera Occidental range of the Andes. On top of the thin air making breathing challenging, gale force winds whipping through this driest of deserts makes it hard to remain standing although our children somehow climbed up some rocks.

Siloli Desert is part of the great Atacama Desert which holds the distinction of being the most arid desert in the world. Entrance to the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve park is next to it.

The Siloli Desert's extreme aridity is due to a double rain shadow effect. Moisture from the Amazon is blocked by the Cordillera Oriental to the east, and Pacific moisture is blocked by the Chilean Coast Range to the west. The result is a hyper-arid landscape where some weather stations have never recorded rain. The colorful mountains are stained by iron oxide (red), sulfur (yellow), and other mineral deposits from ancient volcanic activity.

Desierto de Siloli (Siloli Desert) on Andes Altiplano, Bolivia - this hyper-arid landscape at 15,604 feet elevation shows colorful volcanic mountains stained by iron oxide and sulfur deposits, with some areas receiving no measurable precipitation for decades

There are spectacular rock formations sculpted by sandstone and salt laden forceful winds, the most famous of which is the Árbol de Piedra - the "Stone Tree" sticking out of the desert. It is a 16½ foot natural monolith of mostly quartz with more iron at top which makes the top more resilient.

The Árbol de Piedra is a textbook example of a ventilact, a rock shaped by wind-blown sand. Over millennia, abrasive particles have sandblasted the softer material at its base, leaving the harder, iron-rich cap as a "crown." Similar formations are found in deserts worldwide, but the altitude and stark setting make this one particularly iconic.

|

| The iconic Árbol de Piedra (Stone Tree) rock formation in Desierto de Siloli, Bolivia - this 16.5-foot natural monolith of quartz with iron-rich cap is a classic example of a ventilact shaped by wind erosion over millennia (table-wrapped image showing this wind-sculpted natural monument at 15,604 feet) |

The 18,432 foot Cerro Inacaliri o del Cajón (Volcano Inacaliri) towers above the colorful range of high mountains at the northwest of Siloli. There is a crater lake on a large 1,300 foot diameter crater at the top of Inacaliri which can be hiked to.

Desierto de Siloli (Siloli Desert) on Andes Altiplano, Bolivia, showing the extreme wind erosion patterns and colorful mineral deposits that characterize this hyper-arid region within the greater Atacama Desert system

This extensive photographic documentation of Desierto de Siloli captures the desert's most distinctive features from multiple perspectives. The images progress from establishing shots showing the vast scale of the hyper-arid landscape to focused views of specific geological formations, wind patterns, and atmospheric conditions that define this extreme environment at 15,604 feet elevation.

Desierto de Siloli landscape showing wind-sculpted rock formations and the characteristic sparse vegetation that has adapted to survive in one of Earth's driest environments

Desierto de Siloli with Cerro Inacaliri (Volcano Inacaliri) visible in the distance, showing the relationship between volcanic peaks and the desert basin they surround

Desierto de Siloli atmospheric conditions showing cloud formations and light patterns unique to high-altitude desert environments where extreme aridity creates distinctive optical effects

Desierto de Siloli geological features showing layered sedimentary deposits and erosion patterns that reveal the area's geological history spanning millions of years

Desierto de Siloli panoramic view emphasizing the vast emptiness and scale of this hyper-arid landscape where the earth truly appears to meet the sky

Desierto de Siloli with evidence of wind action on surface materials, showing how persistent gale-force winds shape every aspect of this extreme desert environment

Final perspective of Desierto de Siloli showing the transition zone toward the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve, illustrating how this hyper-arid desert connects to protected alpine ecosystems

Reserva Nacional de Fauna Andina Eduardo Avaroa: Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve

17:11

Map on Sign Board at Entrance of Eduardo Avaroa National Park, Bolivia - this informational display shows the park's extensive 1.7 million-acre protected area encompassing volcanoes, geysers, hot springs, and critical flamingo habitats in the Bolivian Altiplano