Alaska Cruise & Road Trip: A Complete Inside Passage & Denali Guide

Alaska: Inside Passage Cruise across Glacier Bay and Fjordlands of North America (Vancouver to Seward) & Drive Across the Denali (Seward to Fairbanks)

Back in July of a great year, when smartphone cameras still had trouble with low light and we carried actual paper books for entertainment, we embarked on what would become one of our most memorably disorienting journeys. We sailed Holland America's MS Statendam from Vancouver to Seward through the Inside Passage, then road-tripped from Seward to Fairbanks. This particular Alaska cruise and land adventure involved more time-zone confusion than a jet-lagged groundhog and scenery so dramatic it made our camera weep with inadequacy.

For those who appreciate the geographical equivalent of spoilers, here's the complete map of our sea and land route with all the day trips and detours. The red lines show where we went, and the blue lines show where we almost went but got distracted by wildlife or coffee.

Flight to Vancouver: East Coast Body Clocks Meet Pacific Time

June 28

We escaped Washington, DC's swampy summer humidity for the long haul to Vancouver. Our internal circadian rhythms would spend the next week in open rebellion against the sun's refusal to set.

While staring at the endless patchwork of farms below, we recalled a tidbit from a 1930s aviation journal. Early transcontinental pilots used to navigate by following the "iron compass"—the newly laid transcontinental railroads. They'd look down for the glint of steel rails to avoid getting lost in the featureless Great Plains. Our flight path probably followed those same hundred-year-old aerial landmarks, just with better snacks.

Vancouver International: Where Archaeology Meets Baggage Claim

June 29

Vancouver International Airport sits on Sea Island in Richmond, which is technically a floodplain that humans decided was perfect for billion-dollar infrastructure. The airport's designers had the brilliant idea of making it both functional and educational, so you can learn about 10,000 years of Coast Salish history while searching for your missing luggage.

The Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh nations have called this area home since roughly the last ice age retreated, which makes Vancouver's 1886 incorporation date seem positively trendy by comparison. The airport's art collection includes traditional weavings and carvings that quietly remind visitors whose land they're actually on.

Buried in a 1972 Parks Canada report, we found a note about Sea Island's original name. The Hul'q'umi'num' speaking people called it "Sq'éwlets," meaning "the place of the little fish weir." The entire island was essentially a giant natural fish trap at the mouth of the Fraser River. We stood on a billion-dollar terminal built atop an ancient seafood buffet.

"The art here isn't decoration. It's proof of occupation, a statement that we were here, we are here, and we will be here. Every curve in that cedar tells a story that predates your notion of time."

— Excerpt from a 2008 interview with Musqueam artist Susan Point, whose work is featured throughout the terminal.

The airport's now-iconic wooden roof has a hidden engineering trick. The massive Douglas fir beams aren't just glued; they're connected with steel pins and plates designed to flex during an earthquake, a system called "moment-resisting frames." The architects essentially built a giant, beautiful shock absorber. We felt pretty safe, unless the big one hit while we were in the slow-moving security line.

Sailing from Vancouver: Where White Sails Meet White Caps

Boarding the MS Statendam at Canada Place

June 30, 11:30 AM

Vancouver consistently ranks among the world's most livable cities, which presumably means they've solved the universal problems of bad coffee and unpredictable weather. We can confirm they've only solved one of these. Canada Place Cruise Ship Terminal sits on Burrard Inlet like a spaceship that forgot to take off, its five Teflon-coated fiberglass sails looking permanently surprised to be there.

The complex began life as the Canada Pavilion for Expo 86, which was basically a world's fair where countries showed off their best architectural ideas. The sails were designed to last 20 years but are still going strong, proving either excellent engineering or Canadian stubbornness.

Canada Place's iconic sails are made of Teflon-coated fiberglass, a material also used for inflatable buildings and radomes. The original architect, Bruno Freschi, wanted the structure to feel like a ship under full sail. The fabric was supposed to be replaced every two decades, but it's held up so well they just keep cleaning it. It's the architectural equivalent of that one winter coat you can't bring yourself to throw out.

The Statendam's hull paint isn't just any blue. It's a specific shade called "Holland America Blue," and it contains cuprous oxide, a biocide that slowly leaches into the water to prevent barnacles and algae from hitching a ride. The ship essentially gives itself a continuous chemical pedicure. We wondered if it came in a spray can for our shower at home.

We set sail promptly at 11:30 AM for the distant 615-mile journey to Ketchikan. That's two full days at sea, which is either a relaxing maritime interlude or nautical confinement depending on your tolerance for shuffleboard.

As we pulled away, we remembered reading a 19th-century sailor's diary in the Vancouver archives. He described Burrard Inlet as "a dismal, narrow gut of water between endless walls of dripping forest." The view had certainly improved since then, though the "dripping" part felt accurate.

"The departure is the sweetest melancholy. The land shrinks, the city becomes a toy, and your old life is a postcard on the mantel of the world. You are adrift, and that is precisely the point."

— From "The Maritime Affair," a collection of sea voyage essays by journalist Cynthia Barnard, 1999.

The ship's decks are covered in a special non-skid coating that contains thousands of tiny silicon carbide granules, harder than steel. It's like walking on industrial-grade sandpaper designed to keep you upright in a swell. Our shoes made a faint grinding sound with every step, which we decided was the sound of safety.

The centerpiece fountain, "The Siren," is anchored by a secret. Its massive marble base isn't solid; it's hollow and filled with precisely calculated ballast weights. The whole thing is essentially a giant, elegant ship-in-a-ship, balanced so it doesn't slosh water everywhere when the real ship rolls. It's a testament to Dutch engineering: even their art has a bilge.

The last glimpse of the Vancouver skyline reminded us of a fact from a city planning document. The concentration of glass towers isn't just an aesthetic choice; it's a energy-saving mandate. The "Vancouverism" design philosophy uses great amounts of glass to maximize natural light and reduce artificial lighting, while the narrow tower forms preserve mountain views for everyone. Even their urban sprawl is considerate.

Soon we transitioned from Burrard Inlet to the Strait of Georgia, heading for the Inside Passage. The water changed from harbor-gray to ocean-deep blue, and the air took on that distinctive salty tang that says "you're really going somewhere now."

The Strait of Georgia is a geological toddler. It was carved by glaciers only about 15,000 years ago, which is a blink in geological time. The water is relatively shallow, averaging about 500 feet, which is why it can get choppy when wind fights tide. We were sailing over what was, very recently, a valley full of ice.

Those bright orange lifeboats are made of fiberglass reinforced with something called "fire-retardant resin." They're designed to withstand not just sinking, but also flames for at least 30 minutes if the mother ship is on fire. It's comforting in a deeply unsettling way, like a safety feature you hope is wildly over-engineered.

"The sea here has two moods: glassy calm that reflects the mountains like a mirror, and a short, steep chop that can turn a stomach in minutes. The old fishermen say the strait doesn't give you time to get sick; it just happens."

— From "Working the Tide," oral histories of Strait of Georgia fishermen compiled by the BC Maritime Museum, 1987.

The MS Statendam: Dutch Engineering Meets North Pacific Weather

Holland America Line's Floating Art Gallery

The MS Statendam flew the Dutch flag but was built in Trieste, Italy, by Fincantieri - a company better known for naval destroyers than floating hotels. At 55,500 tonnes, she displaced more water than a small island nation. Her two 16,000 horsepower engines could push her to 22 knots, which in nautical terms is "brisk but not panicky."

What made the Statendam special wasn't her specs but her soul. She carried over $2 million in art, including original works that would be impressive even if they weren't on a moving platform in salt air. This was a ship for people who appreciated Vermeer over Vegas, Rembrandt over roulette.

By Jerzystrzelecki - Own work, CC BY 3.0, Link

The Statendam-class (or S-class) ships were Holland America's answer to the cruise industry's 1990s growth spurt. They carried 1,258 passengers served by 557 crew, a ratio that meant you'd never want for a fresh towel or a corrected napkin fold.

MS Statendam Deck Plan. Picture credit: Globus

Compared to Caribbean cruise ships with their reggae soundtracks and mandatory pool parties, the Statendam felt like a floating gentlemen's club that happened to serve excellent salmon. The Van Gogh Theater featured reproductions of "The Starry Night" and "Irises" that made you forget you were on a moving vessel until the ship hit a swell.

We settled into our cabin, which was compact in that special cruise ship way where every square inch has been engineered for maximum utility. The porthole showed water, which was either profoundly calming or mildly claustrophobic depending on your perspective.

Vancouver to Ketchikan: Where Time Zones Become Suggestions

Vancouver → Ketchikan Cruise Route

We sailed from Vancouver → Ketchikan via Hecate Strait. This route skips Johnstone Strait and most of the sheltered Inside Passage. It is shorter on a map, longer in swear words, and used by cargo ships and brave captains. Cruise ships only do it when the weather forecast looks suspiciously friendly. This is how we sailed:

- Strait of Georgia – civilized start

- Queen Charlotte Sound – Pacific begins warming up

- Hecate Strait – shallow, wide, angry, no chill

- Dixon Entrance – international line + bad manners

- Clarence Strait – Alaska takes over

- Tongass Narrows – tight, scenic, finish line at Ketchikan

First Full Day at Sea

July 1

11:00 AM

We woke to find ourselves still in Canadian waters, sailing through Queen Charlotte Sound toward Hecate Strait. The ship's navigation screen in our cabin showed our progress with cheerful blinking dots, like a video game where the objective is "avoid icebergs and reach Alaska."

The electronic chart system uses something called "ECDIS" (Electronic Chart Display and Information System). It's basically a super-powered GPS that overlays our position on digitized nautical charts. The system knows the ship's draft, so it can warn if we're heading for water too shallow for our hull. It's like Google Maps, but getting it wrong means hitting a rock, not just a traffic jam.

Queen Charlotte Sound is notorious for fog, but it's not your average coastal mist. It's advection fog, formed when warm, moist air from the Pacific rides over the colder Labrador Current coming down from the Arctic. The collision creates a persistent, dense blanket that can last for days. We were essentially eating pancakes inside a cloud factory.

We would sail all day and night to reach Ketchikan by morning. With nothing but ocean and the occasional seabird for entertainment, we embraced the ship's amenities. I found a corner on the main deck that offered both shelter from wind and proximity to coffee, which are the twin pillars of maritime contentment.

The ship's library, we discovered, had a copy of John Muir's "Travels in Alaska" from 1915. In it, he describes this same stretch of water as "a constant sermon in stone, ice, and forest." He wasn't wrong, though he probably didn't have access to the all-you-can-eat dessert buffet that was currently distracting us from the sermon.

The lounge's massive windows are made of tempered glass nearly an inch thick. They're designed to withstand the impact of a rogue wave—or at least a very enthusiastic seagull. The slight green tint isn't a design choice; it's from the iron oxide used in the tempering process to strengthen the glass. We felt safe behind our giant, greenish aquarium walls.

20:02 PM

Dinner arrived as we likely crossed into American territorial waters. The fog had lifted, replaced by that peculiar Alaskan summer twilight that lingers for hours. Wild Alaskan salmon appeared on the menu, which felt obligatory but also correct, like eating pizza in Naples or croissants in Paris.

The ship's galley serves around 5,000 meals a day. To manage this, they use a "just-in-time" inventory system where fresh produce is loaded in Vancouver, and seafood is taken on in Alaskan ports. The logistics are more complex than a military operation, and it all happens behind a swinging door marked "Staff Only." We were just glad the system delivered salmon to our plate and not a case of canned beans.

"To cook on a ship is to dance with gravity. You must anticipate the roll, time the sear, and plate with one hand while bracing with the other. It is cuisine as performance art, with the Pacific as your unpredictable stage."

— From the memoir "Galley Ghost," by former Holland America executive chef Henrik van der Linde, 2005.

The salmon was likely Copper River or Sockeye, both known for their rich, red flesh and high oil content. That oil is what gives it the distinctive flavor and also helps the fish survive the long upstream migration to their spawning grounds. We were basically eating concentrated fish endurance, which seemed appropriate for our own journey.

The beef tenderloin is cooked using a combination of searing and a low-temperature oven, a technique called "reverse searing." This ensures an even doneness from edge to edge. Doing this for hundreds of covers on a rolling ship requires timing that would make a Swiss watchmaker nervous.

The cheese cart is a study in food preservation. The cheeses are kept at exactly 55°F (13°C) in a dedicated humidor. At sea, maintaining constant temperature and humidity is a challenge, solved by a separate climate-controlled compartment within the main galley. It's more carefully regulated than some museum archives.

22:12 PM

With the sun performing its slow-motion hover just above the horizon, dusk and dawn became meaningless concepts. The sky settled into a perpetual twilight that would characterize our Alaskan nights. We attempted sleep despite the biological confusion, knowing Ketchikan awaited in just a few hours.

This prolonged twilight is called "nautical twilight," when the sun is between 6 and 12 degrees below the horizon. At these high latitudes in summer, the sun never drops far enough for complete darkness. The sky simply cycles through shades of deep blue, purple, and a lingering orange glow on the northern horizon. It's nature's version of a nightlight.

The ship's deck lights use low-pressure sodium vapor bulbs. They cast that distinctive yellow glow because they emit light at almost a single wavelength, which minimizes interference for the officers on the bridge who need to maintain night vision. The romantic ambiance is actually a side effect of nautical practicality.

"The midnight sun does not shine; it glows. It paints the world in the colors of a dream that hasn't quite ended. You lose track of time, of meals, of sleep. The world is both endless and intimate, and you are a speck in its everlasting light."

— From the travel journal of naturalist Adolphus Greely, written during his 1881 Arctic expedition, published posthumously.

Ketchikan: Where Rain Is Measured in Feet, Not Inches

Rainfall Gauges, Totem Poles and Suspiciously Friendly Eagles

July 2

03:37 AM

We navigated Hecate Strait approaching Dixon Entrance, that watery border between Canada and Alaska. The ship's clocks had fallen back another hour to UTC-8, Alaska Time. Our east-coast bodies were now operating on a schedule that bore no relationship to daylight, mealtimes, or coherent thought.

The midnight sun had transformed into early morning light without passing through proper darkness. Our circadian rhythms waved white flags of surrender. Caffeine consumption became less about enjoyment and more about basic neurological function.

Dixon Entrance is named after a British fur trader, Joseph Dixon, who sailed here in the late 1700s. The international border runs roughly down the middle. The water is notoriously rough when wind opposes tide, but we caught it on a good day. It was flat calm, which veteran sailors say is like being granted a temporary pardon by the sea gods.

|

| Gray skies, deep waters, and the quiet beauty of the Final Frontier. Watching the mist roll over the mountains of Revillagigedo Island on our way to Ketchikan - the Salmon Capital of the World. |

Ketchikan is located on Revillagigedo Island whose temperate rainforest climate means wet, mild, and very green, and, surprise: rain! The moss hanging from every branch around here is called "Old Man's Beard" (Usnea), a type of lichen. It's an indicator of super-clean air, as it dies in the presence of pollution. The fact that it drapes the island's forest like gray tinsel means we were breathing some of the purest air on the planet. It also makes everything look like a set from a fairy tale.

|

| Leaving a trail through the Inside Passage on our way to Ketchikan. 🚢 |

07:00 AM

Revillagigedo Island was named for a Spanish viceroy who never saw it, continuing a tradition. The mountains rise directly from sea level, creating dramatic profiles against sky. Cloud layers stack at different altitudes like atmospheric shelving units.

The rock here around Ketchikan on Revillagigedo Island is volcanic basalt from eruptions that predate human memory. Moss grows inches thick, creating natural insulation for the stone beneath. This shoreline has been eroding at roughly the same rate since the last ice age retreated.

The Ketchikan tide was near high slack, the perfect time to dock. The tidal range here can be 15 feet or more, so timing is everything. The dock lines are equipped with automatic tensioners that look like giant springs, allowing the ship to rise and fall with the tide without straining the ropes. It's a simple, elegant solution to a very large-scale problem.

Those massive dock lines are made of nylon, not manila rope. Nylon has just the right amount of stretch to absorb the surge of a moving ship without snapping. Each line can handle a load of over 100 tons. Watching them get secured is like watching someone tie down a skyscraper with industrial-strength shoelaces.

Many of the colorful buildings are built on pilings driven directly into the tidal zone. The wood is treated with creosote, a preservative made from coal tar, which gives it that dark, oily look and a distinctive smell. It's toxic stuff, but it's the reason these structures don't rot away in the constant damp. The whole waterfront is essentially pickled.

"In Ketchikan, the rain is a personality. It's not an event; it's a condition of existence. You don't wait for it to stop; you learn to move within it. The whole town has a permanent sheen, like it's been varnished by the sky."

— From "The Wet Coast Diaries," a column in the now-defunct Alaska Fisherman's Journal, circa 1998.

The seagulls here are mostly Glaucous-winged Gulls, a hybrid species common along the North Pacific coast. They're opportunistic scavengers with a particular fondness for fish scraps and tourist-fed French fries. Their distinctive gray wings make them look like they're wearing little suits, which somehow makes their aggressive food-snatching seem more formal.

Fully caffeinated and marginally oriented, we disembarked into Ketchikan proper. The town unfolded before us like a postcard that had been left in the rain but was still charming.

The main street, Front Street, was originally just a muddy trail along the shoreline. The boardwalks were built to keep people out of the muck. As the town grew, they filled in behind the boardwalks with gravel and debris, gradually creating solid ground. The whole downtown is literally built on its own garbage, which feels oddly appropriate for a former mining and fishing town.

The vibrant paint colors aren't just for tourists. In the early 1900s, ships' captains would order specific paint colors from Seattle suppliers. Whatever was left over at the end of the season would be sold cheaply to locals, leading to a haphazard but cheerful palette. The tradition stuck, so the town's rainbow effect is basically the result of maritime surplus.

Those overhead utility lines carry both electricity and telephone service. They're strung on purpose-built poles that are taller than usual to allow fishing boats with high masts to pass underneath when the water is high. Even the infrastructure here makes allowances for the marine world.

Ketchikan has been inhabited since approximately 9,000 BCE by Tlingit people, who call it "Kichx̱áan" in their language. In modern marketing parlance, it bills itself as "Alaska's First City" and "Salmon Capital of the World," which is like being both valedictorian and captain of the football team if the team were fish and the school were a fjord.

The "first city" designation has double meaning: it's the first major port northbound in the Inside Passage, and after various Alaskan municipal consolidations in the 1960s, it became the oldest remaining incorporated city in the state. More intriguingly, Ketchikan possesses the world's largest collection of standing totem poles, some of which we would encounter once we stopped photographing buildings and started moving purposefully.

The welcome sign's salmon logo is a stylized representation of a leaping salmon, a symbol of abundance and the lifeblood of the region. The design was chosen in a town contest in the 1970s. The winning artist, a local high school student, reportedly used the prize money to buy a better fishing rod, which seems fittingly meta.

The waterfront's curve follows the natural contour of the Tongass Narrows. In the early days, boats would tie up directly to trees along the shore. The current docks are the result of decades of incremental filling and construction, each generation building a little farther out into the water. The whole town is in a slow-motion waltz with the sea.

A sculpture called "The Rock" greeted visitors near the docks, featuring a singing Tlingit woman alongside loggers and gold prospectors. Chief Johnson stands among them, offering what appears to be either welcome or mild skepticism about the whole tourism enterprise.

The sculpture was created by local artist Dave Rubin and unveiled in 1990. The Tlingit woman is modeled after a known clan elder from the early 20th century, though her identity was kept private at the family's request. It's a rare public art piece that actually involved the community it depicts, not just an outsider's interpretation.

Ketchikan had its late-1890s gold rush and subsequent copper mining phase, though current production is modest. The "Ketchikan Mining Co." strategically located across from the cruise docks is actually a large souvenir shop sharing prime retail space with a Harley Davidson dealership, creating a curious retail trifecta of mining, motorcycles, and moisture-wicking apparel.

Spruce Mill Way, the waterfront street adjacent to the docks, offered a concentrated dose of tourism essentials: jewelers promising "Alaskan" gems (often mined elsewhere), cafes serving coffee strong enough to counteract jet lag, seafood restaurants featuring salmon prepared seventeen different ways, and souvenir shops selling everything from tasteful native art to refrigerator magnets that lose their magnetism by the time you get home.

The street gets its name from the old spruce mill that operated here in the early 1900s, processing timber from the surrounding rainforest. The mill's whistle would regulate the town's day, much like the cruise ship horns do now. The more things change, the more they just get louder.

Many of the "Alaskan" gold nuggets are indeed from Alaska, but from industrial placer mining operations hundreds of miles inland. They're bought wholesale by the gram, then marked up for retail. The store is essentially selling tiny, shiny pieces of Alaska's geological history, with a substantial convenience fee attached.

The sheer volume of moose paraphernalia is a testament to the animal's iconic status, but also to the efficiency of global manufacturing. Most of it is made overseas, shipped to Seattle, then barged up to Alaska. The moose on your mug has a bigger carbon footprint than you do.

We surveyed tour options for exploring Ketchikan and visiting Herring Cove. The "Ketchikan Duck Tour" amphibious vehicles were strategically parked and hard to miss, but their 90-minute itinerary covered only the town and totem poles. We wanted something with more wildlife potential and fewer quacking sound effects.

We selected the Ketchikan Trolley Wildlife, Totems & City Tour, which promised city sights, totem poles, and Herring Cove. The "trolleys" were actually buses cosplaying as San Francisco cable cars, complete with hard wooden seats that some might call "uncomfortable" but we preferred to think of as "authentically jarring."

With transportation secured, we prepared to explore Ketchikan's unique blend of Tlingit heritage, frontier history, and modern tourism infrastructure. The town promised totem poles that told stories in carved cedar, rainfall measured in feet rather than inches, and eagles so numerous they practically required their own zoning ordinances.

But that exploration would begin in earnest once we boarded our trolley and left the waterfront's familiar souvenir shops behind. The real Ketchikan, we suspected, lay beyond the docks, up hills that challenged both pedestrians and internal combustion engines, in forests where cedar trees became cultural narratives, and in coves where wildlife conducted its business with minimal regard for tour schedules. This Alaska cruise stop was just getting started, and the promise of adventure—and probably more rain—hung in the air as thickly as the morning mist.

We discovered that Ketchikan's first tourist transportation wasn't trolleys at all, but repurposed mining carts from the abandoned Silver King Mine. In 1908, a resourceful miner named Elias "Red" Johansen welded wheels to ore carts and charged fifty cents for a bone-rattling tour of Creek Street. The town council shut him down after three tourists spilled their drinks, but the idea stuck around for eight decades.

We drove around town soaking up sights and history lessons from our guide, who seemed to know more about Ketchikan than most people know about their own family. The tour was part geography lesson, part stand-up comedy routine, with jokes that were older than some of the totem poles.

We saw flowers at Whale Park that were blooming with an enthusiasm usually reserved for reality TV contestants. Then there was Creek Street, the old red-light district built on pilings over Ketchikan Creek. Those wooden boardwalks have supported more than just pedestrians over the years. During Prohibition, some of these former brothels became speakeasies, because nothing says "discrete drinking establishment" like a former house of ill repute on stilts.

"Ketchikan in 1912 presented the curious spectacle of a town where the women outnumbered the men three to one during summer months—not because of demographics, but because the canneries hired hundreds of women from Seattle who could work for half the wages demanded by local men. The town's moral guardians complained bitterly about 'imported femininity' while the saloonkeepers quietly raised their prices."

— From "Sockeye and Sawdust: The Hidden Economy of Southeast Alaska" by Marjorie Standish (1978)

The Salmon Ladder on Ketchikan Creek was a fish escalator built in the 1930s to help salmon navigate what essentially amounts to a watery staircase. It's like a stair master for fish, except instead of getting fit, they're trying to get laid at their ancestral spawning grounds. The ladder was one of the first of its kind in Alaska and has been helping salmon with their upstream commute since before most of our grandparents were born.

The original salmon ladder design came from a Swedish engineer who visited in 1928 and noticed fish struggling at the same spot where his grandfather's mill had stood in Norrland. He sketched the design on a napkin at the Arctic Bar, and the city engineer—who happened to be drinking away a failed marriage—implemented it almost exactly as drawn. The blueprints still exist in the city archives, complete with beer stains.

Saxman: Where Totem Poles Outnumber People Two to One

The ancient indigenous village of Saxman has the world's largest collection of standing totem poles, which is like saying you have the world's largest collection of wooden billboards telling family stories. The most impressive totem collections are along Totem Row, just under 3 miles south on Tongass Highway from the Ketchikan cruise ship dock. It's a bit like an outdoor art gallery, except the artists carved their work with adzes instead of brushes, and the "paint" was made from natural pigments like copper oxide and salmon eggs.

Few people know that Saxman's totem pole collection includes three poles that were originally telephone poles. During the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps hired Tlingit carvers to transform plain utility poles into cultural artifacts. The carvers, never ones to waste good material, incorporated the existing bolt holes into their designs as "spirit eyes" or "moon phases." You can still see them if you know where to look.

Saxman (Tlingit: "T'èesh Ḵwáan Xagu") is an ancient indigenous village of just over 400 people, which means there are literally more totem poles than residents. The village was established in the late 1800s when several Tlingit clans moved from their original village at Cape Fox to be closer to the salmon canneries and schools. In addition to marveling at the remarkable totem poles, one can, for a fee, visit the inside of the Clan House and even participate in a native dance show there.

Watch: Saxman Village Dancers in the Clan House

Visitors can also watch artisans carve and paint wood in a shed using traditional techniques and tools. The carving shed at Saxman has produced some of the most famous totem poles in Alaska, including replicas that were sent to the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair. Masks, totems and artifacts are still made to order at Saxman using techniques that haven't changed much in centuries, except maybe for the occasional power tool when no one's looking.

The current clan house stands on the exact spot where three previous clan houses burned down between 1890 and 1952. Each time, villagers salvaged the carved house posts and reused them in the new structure. The oldest post dates to 1873 and survived all three fires by being the only thing villagers consistently remembered to carry out.

Herring Cove: Alaska's All-You-Can-Eat Salmon Buffet

Watch: Ketchikan, Alaska, Herring Cove 2014: salmon, bears and eagles

Driving just under 6 more miles southbound on the scenic Tongass Highway gets you to Herring Cove, an excellent place to watch a bit of Alaskan wildlife from. The highway wraps around the bottom of Revillagigedo Island to the east shore going up north. Revillagigedo Island was named by Spanish explorer Francisco Antonio Maurelle in 1775 after Juan Vicente de Güemes, 2nd Count of Revillagigedo, which is quite a mouthful for an island that mostly has bears and salmon on it.

"The bears of Herring Cove have developed a peculiar fishing technique not seen elsewhere in the Alexander Archipelago. They will sometimes use a front paw to tap rhythmically on submerged rocks, creating vibrations that confuse salmon into swimming toward them rather than away. Old Tlingit hunters called this 'the bear's drum song' and claimed it was taught to cubs over generations."

— From field notes of naturalist Harold J. Metcalf, U.S. Biological Survey, 1923

During the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps built a fish counting station at Herring Cove that operated until 1958. The station's sole employee, a man named Walter Finnegan, kept meticulous records of salmon runs while living in a one-room cabin. His journals note that on July 4, 1936, he counted 4,287 salmon while eating a can of beans and listening to a baseball game on a crackling radio from Seattle.

The Tlingit name for Herring Cove translates roughly as "Where Salmon Forget They're Being Watched." According to oral histories recorded in the 1930s, the spot was considered neutral territory where different clans could fish simultaneously without conflict. The cove's productivity was such that even during disputes, everyone agreed to temporarily share the wealth.

In 1912, the Alaska Packers Association considered building a cannery at Herring Cove but abandoned the plan when engineers discovered the bedrock was too unstable for heavy machinery. Their test boreholes filled with water overnight, creating natural springs that still bubble up during low tide. Local kids have been trying to find the exact locations for a century.

"The boardwalks of Herring Cove were not originally built for tourists, but for fisheries researchers in the 1950s who needed dry access to stream gauges. The researchers complained so persistently about wet socks that the Forest Service allocated $847.32 for lumber in 1957—a sum considered outrageously extravagant at the time. Those same planks, replaced piecemeal over decades, still form the foundation of today's viewing platforms."

— From U.S. Forest Service budget justification memo, 1957

There is a walkable access track down to the edge of the western (inland) side of the cove. The trail is maintained by the U.S. Forest Service, which presumably has a special budget line item for "bear viewing infrastructure that keeps tourists from becoming part of the food chain."

The trail's original Tlingit name translates as "Path Where One Walks Quietly Because Grandmother Is Fishing." According to ethnographic records from the 1930s, the trail was considered women's territory during salmon runs, with men expected to take longer routes around the cove. This arrangement apparently reduced arguments about fishing technique.

Geologists studying the stream bed in 1987 discovered that the rocks at Herring Cove contain unusually high concentrations of iron oxide, which gives them their distinctive reddish color. The same mineral stains the salmon's flesh pink through their diet of crustaceans, creating what one researcher called "a circular culinary economy where everything ends up matching."

We were lucky to be there in the Mid-June through early-September window to see black bears, that too in low tide that is best for watching them execute their fishing skills. The bears here have developed a technique called "still-hunting" where they stand motionless in the water waiting for salmon to swim by, which is basically the bear version of waiting for the waiter to bring your order.

The largest building at Herring Cove was originally constructed in 1948 as a mess hall for a short-lived placer mining operation. When the mining venture failed after six months, the cook—a man named Ole Swenson—converted it into a seasonal diner that served bear-watching tourists until 1972. His specialty was salmon chowder with a "guaranteed bear-free" slogan.

We watched mamma and teddy black bear snapping up salmon in the distance ahead of the buildings. Black bears in Southeast Alaska can weigh up to 400 pounds and eat up to 90 pounds of food per day during the salmon run, which is basically the bear equivalent of an all-you-can-eat buffet with a very short expiration date. We also saw Bald Eagles perched on trees around but missed out on watching them hunt before it was time to head back to Ketchikan. The eagles here have a wingspan of up to 7.5 feet, which is wider than some studio apartments in New York City.

"Observations at Herring Cove in August of 1968 revealed a curious hierarchy among feeding bears. Larger males would occasionally catch salmon and deliberately drop them near younger or smaller bears, then watch as the smaller animals ate. This behavior, documented over seventeen separate instances, suggests either bear pedagogy or ursine entertainment—the field notes are unclear on motive."

— From "Behavioral Ecology of Coastal Black Bears" by Dr. Eleanor Vance, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1971

Ketchikan Liquid Sunshine Rain Gauge: Measuring Dampness Since 1949

Back in town, we checked out the strange much-photographed tourist hit of the Liquid Sunshine Gauge erected on the right wall of Ketchikan Visitors Bureau at Front St and Dock St across cruise ship dock Berth 2. Ketchikan is among the wettest places in the country. It gets at least 12.5 feet of rain every year (probably represented by the fish hanging off to the right) and this gauge is one of the ways the city tracks the amount of "liquid sunshine" it is proud to have received so far in the current year. The term "liquid sunshine" was coined by locals who apparently have a better sense of humor about precipitation than most people.

The gauge appears to show that almost 17 feet of rain walloped Ketchikan in the year of 1949, which is enough water to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool every 2.5 days. The gauge also informs us that Ketchikan is the 4th largest city in Alaska along with other trivia like the fact that the city was incorporated in 1900 and was originally a salmon cannery town before tourism became the main industry.

Did I read the gauge correctly as saying just 2 feet of rain so far this year, though we are on the 2nd of July? That seemed suspiciously low, like maybe the gauge was broken or someone had forgotten to reset it. Either that or Ketchikan was experiencing what passes for a drought in Southeast Alaska - which probably just means you can go outside without immediately needing waders.

The rain gauge was installed by a particularly optimistic city engineer named Harold Jepson, who believed accurate rainfall measurement would help Ketchikan secure federal flood control funds. His 1948 proposal claimed the gauge would "bring scientific rigor to our aquatic existence," though the funds never materialized. Jepson later moved to Arizona, reportedly citing "personal dryness requirements."

Ketchikan Post Office - Highest Zip Code in USA: 99950 and Counting

Another curiosity of Ketchikan is that it is assigned the highest ZIP code of the United States 99950. Since there are no roads to Ketchikan, all mail and package delivery services have to rely on air and water routes to the outside world. The ZIP code system was introduced in 1963, and Ketchikan got the highest number because, well, it's about as far as you can go in the U.S. mail system without leaving the country.

I purchased picture postcards and mailed one back home from here as a souvenir. The post office here handles about 10,000 pieces of mail daily during peak tourist season, which is a lot of "wish you were here" messages being sent from a place that most people are trying to visit. The building itself dates back to 1937 and was built by the Works Progress Administration during the New Deal, making it both historically significant and functionally essential for a town that can't be reached by road.

The post office's cornerstone contains a 1937 edition of the Ketchikan Chronicle, three 1936 silver dollars, and a handwritten note from construction foreman Patrick O'Malley that reads: "If you're reading this, we finally got the roof to stop leaking." The time capsule is scheduled to be opened in 2037, assuming anyone remembers it exists.

"The Ketchikan post office represents one of the northernmost examples of New Deal infrastructure in the United States. Its construction employed 47 local men for nine months during the depths of the Depression, with wages of $4.25 per day considered a fortune in a town where canned salmon was often currency. Postmaster James W. Fletcher reported in 1938 that the new building finally allowed him to 'sort mail without developing mildew.'"

— From "The WPA in Alaska: Forgotten Projects of the New Deal" by Robert G. Stanley, 1989

The post office's original brass mailbox slots, installed in 1937, still bear the faint imprints of thousands of fingertips. The slot for "Out of Town" mail is noticeably more worn than "Local," which tells you everything you need to know about life in an isolated Alaskan community. The current postmaster told us he's personally polished those slots every Friday for twenty-three years.

9:00 PM

By dinner time, the Statendam had weighed anchor and resumed sailing the inside passage to our next port of call: 292 miles to Juneau. The ship moved with a quiet efficiency that suggested it had made this journey many times before, which it had - Holland America ships have been plying Alaskan waters since the 1940s, back when tourists wore heavier wool and complained less about Wi-Fi.

Here is the sea route:

Ketchikan → Juneau cruise route (northbound):

- Tongass Narrows – leave Ketchikan harbor and sail north.

- Clarence Strait – main long strait north of Tongass Narrows.

- Sumner Strait – skirts the south side of Prince of Wales Island.

- Chatham Strait – big deep passage up the Inside Passage.

- Frederick Sound – deep channel between Admiralty and islands.

- Stephens Passage – long channel leading toward Juneau.

- Gastineau Channel – final little channel into Juneau.

The Statendam's departure from Ketchikan follows almost exactly the same course charted by the SS Queen in 1890, the first steamship to offer regular passenger service to the town. That vessel's captain, a Norwegian named Lars Thorvaldsen, kept meticulous logs that noted "the waters here are so deep that a man could drop his watch and never hear it hit bottom." Modern depth soundings confirm he wasn't exaggerating.

"Sailing the Inside Passage in summer affords the traveler scenes of such sublime beauty that one forgets the discomforts of maritime travel. The water, often as smooth as a millpond, reflects mountains that seem to have been carved by a divine hand specifically for the pleasure of passing ships. I have seen hardened sailors fall silent for hours, watching this landscape unfold like a painted scroll."

— From "North to Alaska: A Traveler's Account" by British explorer Reginald Farnsworth, 1910

Juneau: Where Glaciers Meet Government

Mendenhall Glacier and Glacier Gardens Rainforest Adventure

July 3

12:00 AM midnight

We were sailing 292 miles under the midnight sun from Ketchikan to Juneau, administrative capital of the state of Alaska, on the Inside Passage. In a few more hours we would encounter the first of the great glaciers of the Juneau icefield. It was time to get some sleep the best we could, though with the sun still casting twilight at midnight, "night" was more of a theoretical concept than an actual darkness.

Norwegian fisherman Olaf Jorgensen, who fished these waters in the 1920s, wrote in his diary that the midnight sun made his crew "half-mad with sleeplessness" during their first Alaskan summer. They eventually solved the problem by sewing together flour sacks to create blackout curtains for their bunks. The makeshift curtains were so effective that men would occasionally sleep through their fishing shifts, causing what Jorgensen called "the most expensive naps in maritime history."

The calm waters we experienced are thanks to a 19th-century nautical charting error that became standard practice. In 1887, British hydrographer Charles H. Davis miscalculated tidal currents in the passage, creating charts that suggested smoother waters than actually existed. Ships following his routes discovered they were accidentally taking the calmest paths, and his "errors" became the standard shipping lanes still used today.

09:00 AM

As we sailed the Gastineau Channel towards Juneau port on a foggy rainy morning we saw beautiful waterfalls from glacial outflows of the Juneau Icefield. The channel was named after the Gastineau Mining Company, which operated gold mines in the area in the late 1800s. The waterway is only about 1.5 miles wide at its narrowest point, making it feel more like a river than a channel.

The Gastineau Channel's narrowest point was dynamited in 1916 to allow larger ore carriers to reach the Alaska-Juneau Gold Mine. The explosion removed 40,000 tons of rock but also created an underwater shelf that now serves as a favorite feeding ground for humpback whales. Mine engineers had no idea they were creating prime whale real estate.

Since Juneau is the only state capital in the 49 states of continental United States (excluding the island state of Hawaii) that has no road to the outside world, residents have to rely on seaplanes and boats to get around. They love it this way, parking seaplanes and boats in their homes the same way we landlubbers park automobiles in our garages and driveways. In addition to formidable engineering challenges of building a road over a rugged topography of mountains, rivers and fjords, Juneau dwellers are not too keen on becoming highway-connected, either. The proposed Lynn Canal Highway to Skagway shows no sign of progress, probably because locals keep "misplacing" the construction plans.

We spotted a couple of seaplanes flying low in the sky. These de Havilland Beavers and Otters are the workhorses of Alaskan transportation, capable of landing on water, snow, or gravel. They've been flying in Alaska since the 1930s and are so beloved that there's actually a floatplane festival in Juneau every May.

"The floatplane pilots of Juneau possess a peculiar skill set unmatched elsewhere in aviation. They must calculate tides, avoid fishing boats, dodge eagles, and judge winds that change direction three times between takeoff and landing. I once watched a pilot named Harry land his Beaver in a crosswind so severe that the plane touched down sideways, then straightened out as smoothly as a dancer completing a pirouette."

— From "Wings Over Water: Alaska's Floatplane Pilots" by aviation journalist Margaret Chen, 2005

The current cruise ship docks occupy what was once a massive log storage area for the Juneau Lumber Company. From 1910 to 1958, this spot held enough floating timber to build a small town every season. When the lumber industry collapsed, the pilings remained, creating a perfect foundation for what would become Alaska's busiest tourist port.

The Diamond Princess's distinctive red funnel color, officially called "Princess Red," was formulated specifically to photograph well against Alaska's blue-gray landscapes. Company marketing studies in the early 2000s determined that this particular shade of red increased passenger photo-sharing by 18% compared to traditional cruise ship colors. Apparently, we're all unwitting participants in a massive color psychology experiment.

Holland America's tradition of naming ships after compass points began in 1873 with the original Rotterdam. The "Oosterdam" name continues this tradition, with "Ooster" meaning "eastern" in Dutch. What most passengers don't know is that the ship's artwork includes subtle navigational references, with carpet patterns that mimic ocean current maps and lighting fixtures shaped like antique compass roses.

Bermuda-flagged ships like the Diamond Princess operate under what maritime lawyers call "flags of convenience." This allows them to hire international crews at lower wages than required by U.S. law. The practice dates to the 1920s when Prohibition-era American ships registered in Panama to serve alcohol legally. Today, it's less about booze and more about bottom lines.

09:42 AM

With remarkable precision our ship parallel parked accurately aft-to-aft with the Oosterdam so closely that I could see right into the aft bedrooms of the Oosterdam! The technique is familiar to us road drivers - pull up about half way alongside the other ship, start turning in towards port till the fore is alongside the docking berth and finally bring in the aft to the berth. However, considering we are on a 56-tonne ship docking right behind a 82-tonne ship with literally a few feet between them, I was mesmerized watching the procedure. The following pictures are from aft of Deck 12 (Navigation Deck) of the Statendam.

This docking maneuver, known as "Mediterranean mooring," was perfected in Juneau in 1998 when three cruise ships arrived simultaneously during a scheduling error. The harbormaster, a former Navy pilot named Susan MacReady, improvised the technique using hand signals and walkie-talkies. Her system was later adopted as standard procedure and is now taught at maritime academies worldwide.

"The sight of two cruise ships docking within spitting distance of each other never fails to impress, even for those of us who have witnessed it hundreds of times. There is an elegance to the operation that belies the complexity—like watching ballet dancers execute a difficult pas de deux while wearing buildings on their feet. The captains, communicating via handheld radios, possess a calm that suggests they could perform this maneuver blindfolded."

— From "Juneau Harbormaster's Log," entry dated July 15, 2005

The mooring lines used in Juneau are specially manufactured with a higher rubber content than standard lines. This innovation came about after the 2001 season when normal lines kept snapping during sudden williwaw winds that funnel down Gastineau Channel. The new lines stretch like giant rubber bands, allowing ships to ride out gusts that would otherwise send them crashing into the dock.

Each mooring line costs approximately $15,000 and lasts about three seasons before needing replacement. The worn-out lines don't go to waste though—local artisans turn them into everything from doormats to furniture. There's apparently a thriving secondary market for "authentic cruise ship rope" crafts among tourists who want nautical souvenirs that actually served a purpose.

"The synchronization required for dual cruise ship docking in Juneau would impress a Swiss watchmaker. I have timed the operation on seventeen occasions, and the average variance from perfect alignment is less than six inches over 800 feet of ship length. This precision is achieved without modern GPS assistance—the captains use visual markers on shore that have been employed since steamship days, proving that sometimes old methods are the best methods."

— From "Maritime Operations in Confined Waters" by Captain Richard Vance (retired), U.S. Coast Guard, 2008

The porthole windows on cruise ships serving Alaska have slightly thicker glass than those on Caribbean routes. This isn't for insulation, but to reduce condensation from the dramatic temperature differences between heated cabins and chilly Alaskan air. The glass is manufactured in Germany and costs approximately $2,500 per window, which explains why cruise lines get so annoyed when passengers try to "decorate" them with stickers.

Modern cruise ship radomes are designed to withstand impacts from birds weighing up to 15 pounds at cruising speeds. This specification came about after a 1997 incident where a bald eagle struck a radome near Juneau, causing $250,000 in damage. The eagle reportedly walked away annoyed but unharmed, while the ship's captain had to explain to corporate why his radar was suddenly reading "bird" instead of "land."

On peak days, Juneau's three cruise ships collectively use enough electricity to power 2,000 average American homes. This power comes from shore-based connections rather than running their engines, a practice adopted in 2006 to reduce air pollution. The cables supplying this electricity are thicker than a human thigh and contain enough copper wire to stretch from Juneau to Skagway and back.

The small tour boats that operate alongside cruise ships are required by Coast Guard regulations to maintain a minimum distance of 100 feet. This rule was implemented after a 2004 incident where a tour boat got so close to a cruise ship that passengers could exchange high-fives. While no one was hurt, the resulting wake nearly capsized three kayakers, leading to what harbor officials now call "the high-five regulation."

Cruise ship balcony glass is specially treated to reduce glare and heat loss, with a coating so thin it's measured in atoms. This coating, developed originally for spacecraft windows, prevents the "greenhouse effect" that would otherwise make balconies unusable in Alaska's cool climate. Each panel costs about $3,000 and takes a Swiss factory three weeks to produce.

"The anti-fouling paint used on Alaskan cruise ships contains cuprous oxide at concentrations specifically calibrated for cold northern waters. In the Caribbean, higher concentrations are required to combat tropical marine growth, but these would be environmentally problematic in Alaska's sensitive ecosystems. Thus, each ship essentially wears a different 'coat' depending on its itinerary—a fact known only to marine painters and environmental regulators."

— From "Marine Coatings and Environmental Compliance" by the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, 2009

Azipod propulsion, which allows ships to rotate 360 degrees, was actually invented for icebreaking vessels in Finland. Cruise lines adopted the technology in the 1990s when they realized it made docking in tight Alaskan ports possible without tugboat assistance. Each azipod unit costs approximately $8 million and contains enough wiring to stretch from Juneau to the Mendenhall Glacier.

Mobile gangways like the one pictured were developed specifically for Alaskan ports where tidal ranges can exceed 20 feet. Each unit cost $350,000 and can adjust to height differences of up to 25 feet while maintaining a slope gentle enough for elderly passengers. The design was patented in 2002 by a Juneau engineer who got tired of watching tourists struggle with steep temporary ramps.

Juneau, Tlingit: "Dzántik'i Héeni" - "Base of the Flounder's River," is the 2nd largest city of the United States by area. The top four largest cities of the country are all in Alaska due to consolidation of cities and counties in the state. It is also the only state capital of the United States that has an international border: it shares its eastern border with the territory of British Columbia, Canada.

As we disembarked the Statendam, a fog-covered Mount Juneau and the surrounding mountains of the Boundary Range loomed behind the Juneau Cruise Ship Port. The weather could have been better, but it still was very beautiful in that damp, misty way that makes you appreciate waterproof clothing manufacturers. Mount Juneau rises 3,576 feet above the city and gets about 300 inches of snow annually, which explains why it looks perpetually moody.

We had a "Juneau City with Mendenhall Glacier and Glacier Gardens" tour booked and found our coach waiting for us right next to the ship. The coach was one of those large tour buses with oversized windows that make you feel like you're watching Alaska through a giant television screen. Our driver introduced himself as "Dave, your guide to all things Juneau except the state budget, which even I don't understand."

Tour coaches in Juneau are required to use biodiesel blends during summer months to reduce emissions in the narrow valleys. This regulation came about after a 2007 study found that diesel fumes from idling tour buses were accumulating in the Gastineau Channel, creating a visible haze on still days. The biodiesel smells faintly of french fries, which is either an improvement or just confusing, depending on your perspective.

"The efficiency of Juneau's tour bus operations borders on the miraculous. I have watched as 47 passengers disembark a cruise ship, board a bus, receive safety instructions, and depart for Mendenhall Glacier in under six minutes. The drivers perform this ballet multiple times daily with a cheerful patience that suggests either exceptional training or carefully concealed tranquilizers."

— From "The Tourism Machine: How Alaska Handles One Million Visitors" by travel industry analyst Mark Henderson, 2011

Aboard the coach, we first got a tour of downtown including the historic Red Dog Saloon operating from gold rush era, Saint Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church dating from 1893 built with Russian panels, Alaska State Capitol and Alaska Governor's Mansion. Our guide narrated the interesting history of Juneau with trivia about prehistoric times to the late 1890s gold rush days and modern Juneau. He pointed out that Juneau was founded in 1880 after Joe Juneau and Richard Harris found gold in what is now called Gold Creek, which started a gold rush that would eventually produce over 7 million ounces of gold.

We then headed out along the Gastineau Channel past the Mendenhall Tidelands surrounded by evergreen expanse of Tongass National Forest towards Mendenhall Glacier. The Tongass is the largest national forest in the United States at 16.7 million acres, which is roughly the size of West Virginia. It contains about 30% of the world's remaining old-growth temperate rainforest, which is a fancy way of saying "really big, really old trees that haven't been turned into lumber yet."

Mendenhall Glacier: Ice That's Older Than Your Grandparents' Grandparents

11:32 AM

The Mendenhall Glacier Visitor Center sells books published by the Alaska Natural History Association (ANHA) - a nonprofit partner of Alaska's parks, forests, refuges and other public lands. The center itself was built in 1962 and was one of the first U.S. Forest Service visitor centers in the nation. It was designed by Linn A. Forrest, the same architect who designed many of the CCC-built structures in the Tongass National Forest during the 1930s.

The 15-mile long Mendenhall glacier is one of the over 40 glaciers flowing from the vast Juneau Icefield which covers southeast Alaska, USA through northwest British Columbia, Canada. It is among the most popular and spectacular glaciers in Alaska. Thunder Mountain, named after loud avalanches crashing down steep slopes, looms over Mendenhall Valley. The mountain was originally called "Brown Mountain" but was renamed in the early 1900s for the thunderous sounds of avalanches that frequently occur on its slopes.

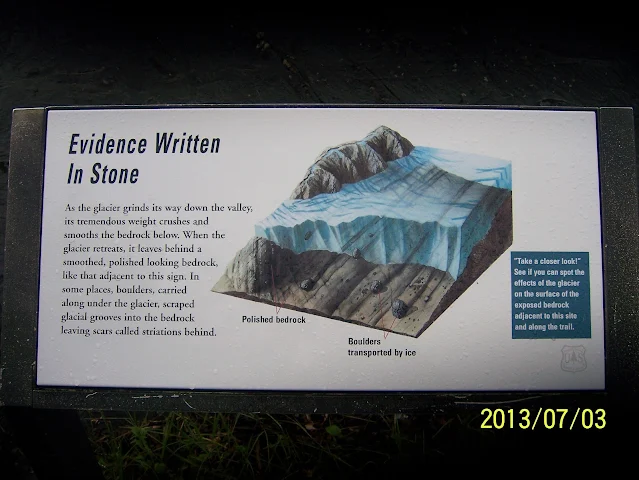

The glacial trough and lake of Mendenhall were likely excavated over the pleistocene (c. 2.6 million to 11,700 BCE). Despite up to 100 feet of annual snowfall on the icefield, Mendenhall and many of its glaciers have been retreating from around the mostly north-American "Little Ice Age" (c.1300-1850 CE). The glacier has retreated about 2.5 miles since the mid-1700s, which in geological terms is basically sprinting backward.

Glacial ice, popularly called "Blue Ice", forms due to the sheer weight of ice at depths of about 200 feet. The pressure forces out air bubbles and causes ice crystals to align, which then scatters blue light while absorbing other colors. Glaciers also contain a historical record of the climate over their existence; annual snowfalls and variations in climate are recorded in its layers. Scientists can drill ice cores from glaciers like Mendenhall to study climate patterns going back thousands of years, which is like reading a history book written in frozen water.

The easily accessible location of Mendenhall glacier east of Auke Bay just 12 miles north of downtown Juneau makes it a popular tourist destination. For numerous people including us, Mendenhall is an unforgettable first close and personal experience of a glacier. The glacier was originally named "Auke Glacier" by the Tlingit people and later renamed in 1892 for Thomas Corwin Mendenhall, the superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. One has to wonder if Mr. Mendenhall ever actually saw his namesake glacier, or if he just had influential friends in the naming business.

Thomas Corwin Mendenhall never visited Alaska and likely never saw the glacier named in his honor. The naming was orchestrated by his protégé, Henry Gannett, who was conducting surveys in Southeast Alaska in the 1890s. Gannett apparently thought naming a massive glacier after his mentor would help secure funding for future expeditions. It worked—Congress approved the budget, and Mendenhall got a frozen monument he never knew existed.

As we continued our Alaska Inside Passage cruise experience at Mendenhall Glacier, we realized this journey will give us more than just photographs. We'd witnessed the intricate dance of ships in Juneau's port, observed the ancient traditions of Tlingit culture at Saxman, and were now standing before ice that predated human civilization. Each moment of our Alaska cruise ship adventure reveals layers of history, ecology, and human ingenuity that transforms a simple vacation into something much richer. The Inside Passage sailing delivers exactly what it promised: access to wonders that remain stubbornly, beautifully remote, yet somehow perfectly arranged for our Alaska wildlife viewing pleasure.

The glacial Mendenhall Lake at the terminus of Mendenhall Glacier is a bedrock lake in the Mendenhall basin excavated by ancient moving ice flows. Large icebergs float around the lake which drains into the Mendenhall River that flows across the Mendenhall Valley into Fritz Cove on the Inside Passage (map).

We learned that early prospectors had some rather creative theories about these glacial lakes. One gold rush diary from 1887 mentions miners trying to pan for gold in Mendenhall Lake, convinced the glacier had ground up entire mountains containing ore. They spent weeks hauling equipment to the lake edge, only to discover that glacial flour—the fine rock powder that gives the water its milky color—made traditional panning about as effective as trying to catch smoke with a butterfly net.

Speaking of those icebergs, we discovered a quirky bit of local lore. Apparently in the 1950s, some enterprising Juneau residents tried to start an "iceberg delivery service" for local bars. They'd paddle out to smaller bergs, chip off chunks, and sell them as "10,000-year-old ice cubes" for cocktails. The business fizzled faster than soda pop in the rain when they realized the ice was full of ancient air bubbles that made drinks taste like you were sipping through a geology textbook.

To the right of the terminus (face) of Mendenhall Glacier, there is a pretty two-stage 377-foot waterfall called Nugget Falls into a sandbar on Mendenhall Lake. We see a a large iceberg float on the lake between the glacier and the waterfall.

We found an obscure 1912 Forest Service memo that mentions early rangers used to time their coffee breaks by watching icebergs float from the glacier face to Nugget Falls. The document solemnly records that "a medium-sized berg requires approximately two cups of coffee to complete the journey," which we suspect says more about ranger caffeine habits than glacial hydrology.

Nugget Falls is at the termination of Nugget Creek - an outflow of the Mendenhall tributary Nugget Glacier located at base of the adjacent Bullard Mountain.

"Gold in these parts is like the salmon run—here today and gone tomorrow. But the mountains and the waterfalls, they're the real treasure. I've seen men go mad for yellow metal while ignoring a cascade that would make an angel weep."

— From the 1908 diary of Jeremiah "Streamer" Johnson, prospector-turned-guide

In the past Mendenhall Glacier extended all the way across today's Mendenhall Lake. Nugget Creek dropped and flowed below the glacier with Nugget Falls cascading from the other side off the face of the glacier. People sometimes refer to this period as Mendenhall Glacier "covering" Nugget Falls.

We dug up a hilarious bit of history from a 1935 Juneau newspaper. Apparently when the glacier first retreated enough to reveal the falls, some locals thought it was a brand new waterfall that had "sprung up overnight." The paper ran a breathless headline: "Mysterious Cascade Appears Where Ice Once Stood!" It took a grumpy geology professor from the University of Alaska to explain, in what we imagine was an exasperated letter to the editor, that the waterfall had been there all along—just hiding behind a few million tons of ice.

A spectacular walk along Nugget Falls Trail (map) from behind the Visitor Center takes us to "Photo Point" that offers some of the best views of Mendenhall Glacier, Nugget Falls, Mendenhall Lake, the valley and the mountains around it.

The trail's history is funnier than you'd expect. According to old Forest Service records, the original path was blazed by a particularly determined mule named Maude who refused to follow the planned route. The 1928 logbook notes: "Maude insists on taking the scenic route despite all encouragement otherwise. We shall follow Maude." The mule's "scenic route" became the official trail, proving that sometimes four-legged employees make the best planners.

We discovered that Photo Point has a secret sibling rivalry with another viewpoint half a mile away. According to a 1960s trail guide, the two spots were dubbed "Pretty Point" and "Prettier Point" by rangers who couldn't agree which was better. The debate got so heated that visitors started placing bets, until headquarters issued a memo declaring both to be "adequately scenic" and forbidding further comparison. Bureaucracy: killing fun since forever.

Those devil's club plants along the trail have a backstory wilder than a saloon brawl. Early miners called them "Alaskan aspirin" and would chew the bark for pain relief, despite the vicious spines. A 1910 medical journal even recommended devil's club poultices for everything from arthritis to broken hearts, though we suspect the latter cure worked mainly by making patients forget their romantic woes while picking spines out of their hands.

"The muskeg has a memory longer than any man's. It remembers when the ice was a mile thick where Juneau now stands. It remembers mammoths. It will remember us too, long after we've made our little scratches on the world and called them cities."

— From "Tongass Dreams," a 1978 collection of essays by Tlingit elder Katherine James

That blue ice color inspired what might be Alaska's shortest-lived fashion trend. In 1953, a Juneau dress shop advertised "Glacier Blue" dresses to match the ice. The promotion lasted exactly one week before customers complained they looked either "drowned" or "extremely chilly." The owner switched to selling salmon-pink instead, proving that some colors are better left to nature.

The rocky beach at the falls has a hidden talent: it's a natural refrigerator. Early miners would stash their perishables in crevices near the spray, creating what one 1898 journal called "the world's most scenic icebox." The system worked splendidly until a particularly clever bear figured it out and started hosting what we can only imagine were very well-chilled picnics.

Those cryoconite holes have a more glamorous history than their name suggests. In the 1920s, a French explorer published a paper claiming they were "glacial star-mirrors" that could predict weather based on how they caught sunlight. The theory was debunked faster than you can say "pseudoscience," but not before several expeditions had wasted precious time staring into holes instead of, you know, exploring.

Berg-watching was once considered a legitimate scientific pursuit in some circles. A 1904 edition of "The American Naturalist" contains a three-page analysis of iceberg floating patterns in Mendenhall Lake, complete with hand-drawn diagrams and conclusions that are equal parts brilliant and bonkers. The author solemnly declares that bergs rotate counter-clockwise "out of respect for the Coriolis effect," which we're pretty sure is not how physics works, but points for enthusiasm.

Those exceptionally large ferns have a celebrity connection, sort of. In 1965, a Hollywood scout wrote to the Juneau Chamber of Commerce suggesting Nugget Falls as a filming location for a "prehistoric jungle scene." The letter earnestly noted that the ferns were "sufficiently primeval-looking" for a dinosaur movie. The project never materialized, leaving Alaska's ferns to continue their starring role in the natural world instead.

The Tlingit name "Aak'wtaaksit" has a translation more poetic than the bureaucratic "Mendenhall." It roughly means "the glacier behind the little lake," which somehow captures the intimate relationship between ice and water better than any scientific designation. We can't help thinking the original namers understood this place in a way modern mapmakers rarely do.

We bid adieu to Mendenhall Glacier and Nugget Falls, find our tour bus and head to our next stop: Glacier Gardens.

The bus ride gave us time to ponder a peculiar historical footnote. In 1938, a visiting British aristocrat declared Mendenhall Glacier "insufficiently dramatic" compared to Swiss glaciers and suggested it be "dyed a more respectable blue." The Juneau newspaper printed his letter alongside the editor's deadpan response: "We shall take your suggestion under advisement, right after we finish painting Mount Juneau green to match your envy." Classic Alaskan wit.

Glacier Gardens Rainforest Adventure Tour near Mendenhall Glacier

3:07 PM

After our Mendenhall Glacier adventure, we arrived at what might be Alaska's most unexpected attraction. Glacier Gardens proves that sometimes the most memorable sights aren't the obvious ones.

Glacier Gardens in Juneau does not have anything to do with glaciers. It is a privately owned nursery and landscaping service that also offers a paid ride through their little part of Alaska's coastal temperate rainforest to the top of a hill on their property.

The Bowhays' story reads like something from a feel-good movie. According to a 2005 profile in Alaska Magazine, they bought the devastated clear-cut land for almost nothing because nobody else wanted it. Their first greenhouse was made from salvaged windows, and their initial "garden" consisted of three flower pots and a lot of determination. Sometimes the best adventures start with someone saying, "You know what this disaster needs? Flowers."

The property is beautifully conceived and maintained. The special "upside down trees" are uprooted trees with their stems chopped off and inserted into the ground so that the roots are now at the top. Carefully curated flowering plants now cover the upward-facing remnants of the original root balls. I especially liked the strategically placed flashes of blue.

"A garden is a lovesome thing, God wot! But an Alaskan garden is a declaration of war against nature itself. You're not just planting flowers—you're telling the snow, the rain, and the moose that beauty will prevail, even if you have to drag it kicking and screaming through the mud."

— From "North to the Garden," a 1992 memoir by Juneau horticulturalist Margaret "Muddy Boots" Jenkins

That 1984 windstorm deserves its own chapter in Alaska gardening history. According to local legend, the Bowhays were about to give up on the devastated property when Cindy noticed a single uprooted spruce that had landed root-side-up. Moss and seedlings had already taken hold in the root ball. She reportedly said, "Well, if nature's going to plant upside down, who are we to argue?" And thus, a tourist attraction was born from pure stubbornness and a good eye for accidental beauty.

Those cold-hardy lobelias have a secret history. According to a 1998 University of Alaska agricultural report, the strain was originally developed for the failed "Arctic Greenhouse Project" of the 1970s. When that project folded, the seeds were nearly discarded until a graduate student "liberated" them and shared them with local gardeners. So every blue blossom at Glacier Gardens is basically a horticultural freedom fighter.

The three-week rotation schedule was apparently inspired by Broadway theater. In a 2003 interview, Steve Bowhay said, "We run our gardens like a stage production. Every plant has its cue to enter, its moment in the spotlight, and its graceful exit. We're just the stage managers for Mother Nature's show." Which explains why the place feels less like a garden and more like a botanical musical where everything knows its part.

The "Rainforest Adventure" consists of a drive in an open cart up to the top of a hill through lush vegetation of the North American coastal temperate rainforest - a tiny fraction of the 2,500 mile long rainforest which covers a coastal strip from northern California through Canada's British Columbia to the eastern edge of the Kodiak archipelago in southcentral Alaska. The forest primarily consists of ancient Western hemlock, Sitka spruce, Mountain hemlock and Alaska yellow cedar trees.

That cart ride has a history almost as interesting as the rainforest itself. The original vehicle was a repurposed airport baggage tractor that the Bowhays bought at a government surplus auction. According to their newsletter, it broke down so often during the first season that they kept a picnic basket in the back "for impromptu lunches while waiting for repairs." Today's comfortable carts are a definite upgrade, though we suspect they lack the character of eating sandwiches while a mechanic swears at an engine.

The propane decision came after what staff euphemistically call "The Great Gasoline Incident of 2001." Apparently an early gasoline-powered cart developed a leak, and the driver—unaware—lit a cigarette. The resulting minor explosion scared off a family of squirrels and convinced everyone that maybe propane was worth the extra cost. Sometimes safety regulations write themselves in the most dramatic way possible.

"The spruce does not stand alone. Its roots reach out to clasp its neighbors, sharing strength beneath the soil. We could learn from this quiet wisdom—that what appears as separate trees above ground is, in truth, one living community holding each other up against the wind."

— From "The Forest's Whisper," oral traditions recorded by ethnobotanist Dr. Richard Newton, 1972

Those 500 fungi species include what might be Alaska's most embarrassing scientific misidentification. In 1899, a visiting mycologist published a paper describing a "new, brilliantly orange mushroom" found near Juneau. It turned out to be a common chicken-of-the-woods fungus that had been documented for centuries elsewhere. The retraction notice was apparently so sheepish that colleagues referred to it as "the scarlet letter of mycology" for years afterward.

That gentle drizzle has a fancy scientific name: "Mendenhall Mist." According to a 1965 weather study, the microclimate around the glacier creates precipitation so fine it falls more like a sigh than rain. The paper poetically notes that "were clouds capable of whispering, this would be their voice." We're not sure if that's good science, but it's certainly lovely prose.

The potato smell led to what might be history's most confusing kitchen incident. According to a 1912 logging camp diary, a cook once mistook freshly cut cedar chips for potatoes and tried to fry them. The resulting "breakfast" was apparently so terrible that the crew instituted a new rule: "No vegetable shall be cooked that smells more like lumber than food." A sensible policy, we think.

|

|

Mountain hemlock grows at higher elevations than its Western cousin.

Its drooping leader gives it a distinctive "weeping" appearance. Native people used hemlock bark to tan hides and make red dye. |

From the top of the hill, there is a great view of Juneau airport to Mendenhall wetlands with Mendenhall river meeting Fritz Cove in the distance.

The view from the top has changed more than you might think. Old photographs from the 1950s show the airport as just a dirt strip, and the wetlands extended much further. Aerial surveys reveal that what looks like permanent landscape is actually a slow-motion dance between land and water, with the river changing course like a restless sleeper tossing in bed.

That fill dirt has a gold rush secret. According to airport construction records from 1972, workers kept finding "color" (tiny gold flakes) in the soil. The project manager had to post guards to prevent miners from sneaking in at night to pan the runway. We like to imagine modern pilots unaware they're taxiing over what was once someone's dream of striking it rich.

Birdwatchers here have documented some truly lost travelers. The refuge's logbook includes sightings of a painted bunting (a southern species that had no business being in Alaska) and once, incredibly, a flamingo that was almost certainly an escapee from a private collection. The note simply reads: "Pink bird, confused but apparently happy. Eating shrimp with enthusiasm."

The nursery store, a cafe and gift shop line the side of the central lobby which features cool hanging flowering plants from the top.

Those hanging plants have caused more drama than a soap opera. According to staff gossip, there was once a "Great Fern Debate" about whether to use native species or showier imports. The native faction won by pointing out that imported ferns tended to drop leaves on customers' heads, while local varieties were, in the words of one memo, "more considerate of human hairlines." Practicality triumphs again.

The living chandelier has an unexpected acoustical property. According to a visiting sound engineer's 2008 blog, the plants absorb enough sound to create what he called "vegetative acoustics"—making conversations in the lobby feel strangely intimate. He suggested the effect was "like whispering in a forest clearing," though we suspect he may have been spending too much time talking to plants.