Moscow Travel Guide: Gingerbread Cathedrals, Subterranean Palaces and Immovable Bells

We spent a few whirlwind days before hopping on our train to Mongolia. You know you're in Russia when even the subway stations look like they belong in a tsar's palace. We visited , which apparently isn't actually red - the name comes from 'krasny' meaning 'beautiful' in Old Russian. Who knew?

Moscow has a population of about 13 million residents within the city limits, making it the most populous city entirely in Europe. The Kremlin and Red Square were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1990. So yes, our drizzle - soaked wandering came with a side of world history.

Vagabond Tip Get a Troika card instead of single metro tickets. It reduced the per - ride fare in 2017 and saved time. Stand on the right. Walk on the left. Moscow commuters take this very seriously.

Vagabond Tip Red Square is open day and night unless closed for official state events. Early morning gives the cleanest views before the tour buses roll in.

Reaching the Aeroflot check - in at Washington Dulles felt like the opening scene of a Cold War spy movie. The agent examined our Russian visas with the intensity of a security services officer looking for microfilm. She disappeared with our passports for fifteen minutes that felt like fifteen years, returning with a manager who looked equally puzzled.

Turned out they were hunting for a flight reservation out of Russia. We explained we were leaving via train at the Mongolian border on the Trans - Siberian Railway. The manager's eyebrows nearly hit the ceiling. "Train? To Mongolia?" We presented our electronic train tickets like they were diplomatic immunity papers. After what felt like a serious discussion, they finally stamped our boarding passes with visible skepticism.

The full Trans - Siberian Railway from Moscow to Vladivostok runs about 9,289 km. Nonstop services take about seven days, depending on the train. Yaroslavsky Railway Station is the classic Moscow departure point. Long tracks. Longer stories.

Our Aeroflot flight finally touched down at Sheremetyevo Airport, where we discovered that Russian baggage handlers have a talent for making luggage look like it survived a minor plane crash. The taxi ride to our hotel gave us our first glimpse of the - wider than expected and frozen at the edges despite it being July.

The banks were among the first settled areas in the region for a boring reason: water. Over the centuries, dredging, embankments and reservoirs changed the river’s depth and flow, so old descriptions don’t always match what we see today. If you want the short version: Moscow reshaped its river the way it reshaped its skyline - repeatedly and with confidence.

|

|

Moskva River, Moscow The river doing its best impression of not being frozen. This stretch used to host medieval fishing competitions. |

The Moskva River symbolized tsarist power so much that Peter the Great ordered special "pleasure barges" just for floating parties. During Soviet times, they built restricted reservoirs along its banks for Politburo members' restricted facilities. The river played a key role in Moscow's industrialization, providing water power for factories that mostly produced more factories.

Our Moscow Travel Crash Pad

We checked into Katerina City Hotel, which seemed to be where all the international tourists who couldn't afford the Four Seasons but didn't want Soviet - era plumbing ended up. The place had that peculiar Russian hospitality - efficient, slightly grim, but with surprisingly good wifi.

The hotel occupied that sweet spot between "central enough to be convenient" and "not so central you hear traffic all night." It was in the Paveletskaya District, an area that during Soviet times manufactured train parts and now manufactures overpriced hotel breakfasts.

|

|

Katerina City Hotel Bar, Moscow The hotel bar where modern hospitality provides universal familiarity. $15 for a vodka that costs $2 outside. But the free peanuts almost made it worth it. |

What's interesting about Paveletskaya District is that it was named after the Paveletsky Railway Station, which itself was named after the town of Pavelets. The town's main claim to fame? Not much that most travelers would recognize. It's like naming something after your most boring relative.

The hotel was just a short walk from Paveletskaya Metro Station, which meant we could reach faster than you can say "perestroika." The nearby Paveletsky Railway Station provided express trains to , in case you needed to escape quickly - a feature many tourists have appreciated over the years.

Vagabond Tip Central Moscow metro signage is usually bilingual (Russian and English). Step outside the tourist core and English fades fast - offline maps with Cyrillic names help a lot.

|

|

2-Y Shlyuzovoy Most Peshekhodnyy Bridge, Moscow The bridge with the name no tourist can pronounce twice. Built in 1997. Locals call it 'that metal thing near the hotel.' |

That shiny beast in the background of the Moscow skyline nearby is the Novospassky Monastery, a historic 14th - century fortress - monastery that served as the burial place for the Romanov ancestors before they became Tsars. It features brilliant domes and thick white walls that historically protected the southeastern approaches to the city. While it isn't the Kremlin, its imposing presence over the river provides a heavy dose of Russian architectural drama without the massive queues.

Those big Soviet - era apartment blocks come with endless Moscow folklore, including the usual “security services lived there” rumors. What’s real (and well known in the Soviet context) is that many ministries and big state employers had their own housing allocations, with access and privileges tied to job and rank. The rest is often street - corner storytelling - entertaining, but not the kind of thing we’d bet a metro pass on.

Housing in the Soviet system could be deeply hierarchical and the higher your status, the better your odds of getting a nicer place in a better spot. Beyond that, we stuck to what we could actually see: a river bend, a wall of concrete balconies and a neighborhood that has gone from heavy industry to “please scan this QR code to buy coffee.” Moscow changes fast. Soviet rumors travel even faster.

Speaking of that industrial complex visible from our window, many Moscow factories during the Cold War operated with dual - use capabilities. A factory producing tractors or household goods could, theoretically, be retooled to produce military hardware in the event of a conflict. It was a pragmatic, if slightly paranoid, approach to urban industrial planning that ensured the city was always functionally prepared for the worst.

|

|

Moskva River evening view from hotel, Moscow Evening lights make everything look less Soviet. Those cranes are building luxury condos for oligarchs. The river looks almost clean from this distance. |

After checking in, we hit the Alex Bar off the lobby for breakfast. The place had that post - Soviet aesthetic: lots of chrome, uncomfortable chairs and a menu that featured both borscht and cappuccino. We ordered what turned out to be surprisingly expensive hash browns.

Vagabond Tip Most mid - range restaurants accepted cards in 2017, but smaller cafés sometimes preferred cash. Carry some rubles. It saves the awkward card - reader stare - down.

|

|

Breakfast at Alex Bar, Moscow Breakfast: where capitalism meets communism on a plate. The sausages were probably 50% sawdust, 50% nostalgia. But the coffee was surprisingly not terrible. |

Moscow Travel Underground: Metro Palaces

We walked to Paveletskaya Metro Station, which is less a subway station and more an underground palace that happens to have trains running through it. The was Stalin's pet project to show the world that Soviet workers deserved beautiful things too. Each station was designed by different architects competing for Stalin's approval - a high - stakes commission during an era when falling out of official favor carried severe consequences.

|

|

Paveletskaya Metro Station, Moscow Descending into Stalin's underground kingdom. These escalators are longer than some subway lines. No pushing - it's practically a law here. |

Paveletskaya Station has been hauling Muscovites around since 1950, when it opened as part of the first segment of the Koltsevaya line. It’s classic Soviet Metro: marble, chandeliers and heroic vibes turned up to eleven. Early décor included a platform - end medallion showing Lenin and Stalin together. During de - Stalinization in the early 1960s, that imagery was removed and today you’ll see Pavel Korin’s artwork featuring the Soviet coat of arms held by a worker and a peasant woman.

We took the train to Okhotnyy Ryad station, which translates to "Hunter's Row" - named after the 18th - century market where hunters brought in poultry and game to trade. It later became a bustling, somewhat chaotic commercial hub before the Soviets cleared it for monumental development.

|

|

Red Square, Moscow Where history happens and tourists get lost. That building on the left used to be the Upper Trading Rows. Now it's just another place to buy overpriced souvenirs. |

Moscow City Center: Where Past Meets Present

Downtown Moscow around Manezhnaya Street is where 19th - century architecture collides with 21st - century capitalism. The street gets its name from the Moscow Manege, a massive riding school built in 1817 for Alexander I's cavalry. The building was constructed specifically to commemorate the victory over Napoleon five years earlier.

|

|

Central Moscow around Manezhnaya Ulitsa Moscow's version of 'old meets new.' The monumental Four Seasons Hotel is a modern replica of the historic Hotel Moskva. Now it sells luxury to oil executives. |

The architecture here is what you'd get if a tsar, a communist and a capitalist had a building design competition. Neoclassical 19th - century mansions stand next to Stalinist wedding cakes, which stand next to glass skyscrapers built by people who made fortunes in the 1990s aluminum trade.

The area buzzes with wide boulevards where luxury cars navigate around babushkas selling pickles from coolers. It's Moscow's version of "trickle - down economics" - the Mercedes drivers might not notice the pickle sellers, but at least they share the same sidewalk.

|

|

Moscow City Center streets Moscow's answer to Fifth Avenue or Champs-Élysées. Those cafes charge $10 for coffee that costs 50 rubles elsewhere. But the people-watching is worth every overpriced kopek. |

Nearby stands the State Historical Museum, which looks like a red brick fairy tale castle. During the late 1940s and 1950s, Soviet museums often hosted exhibitions intended to prove Russian primacy in global inventions, from the radio to the lightbulb. The State Historical Museum itself has survived numerous regime changes, adapting its vast collection of Russian artifacts to fit the prevailing historical narrative of the era.

In the evening, the area transforms as lights illuminate buildings that have seen everything from tsarist balls to Soviet parades to capitalist shopping sprees. The magical atmosphere almost makes you forget you're paying $20 for a sandwich.

Kremlin and Red Square: Russia's Beating Heart

"Kremlin" simply means "fortress inside the city," which is like calling the Pentagon "that office building in Virginia." The Moscow Kremlin has been the official residence of Russian rulers since Ivan the Great decided wooden walls weren't intimidating enough. Today, "the Kremlin" is shorthand for the Russian government, which is fitting since both are hard to get into.

St. Basil's Cathedral is Russia's architectural equivalent of a fever dream. Officially called the Cathedral of the Intercession of the Most Holy Theotokos on the Moat (catchy, right?), it's the building that says "Moscow" in movies, much like the Eiffel Tower says "Paris" or a traffic jam says "Los Angeles."

Vagabond Tip St. Basil’s Cathedral needs a separate interior ticket. Check opening schedules around Orthodox holidays when closures can happen.

|

|

St. Basil's Cathedral, Red Square Up close, it's where geometry gets religious. The patterns were inspired by medieval Russian embroidery. Or maybe Ivan just really liked colorful hats. |

Ivan the Terrible commissioned it between 1555 and 1561 to celebrate beating the Khanate of Kazan. The architects were Postnik Yakovlev and Barma. While the legend of their subsequent blinding is well - known, historical records suggest they remained gainfully employed and fully sighted for years afterward, proving that even 16th - century Tsars had to contend with viral misinformation.

|

|

St. Basil's Cathedral, Red Square The cathedral's 'organized chaos' design philosophy. Each chapel commemorates a different battle victory. Ivan wanted to make sure God knew exactly who won. |

The architecture is what happens when Russian medieval design, Byzantine influences and wooden folk architecture have a party and invite too many colors. The vibrant onion domes are the main attraction - each representing a different church inside. The central tented roof is surrounded by eight smaller chapels, giving it that "exploding cupcake" look.

The asymmetric layout and brilliant colors were added in the 17th century, because apparently the original white stone version wasn't trippy enough. Inside, it's a labyrinth of narrow corridors and small chapels that make you feel like you're exploring a religious hedge maze.

St. Basil's survived Napoleon's plans to blow it up in 1812 (rain as the story goes extinguished the fuses) and the Soviet era when officials wanted to tear it down for military parades. A popular story says when architect Lazar Kaganovich removed the cathedral from a scale model of Red Square to show Stalin how much more room there would be for tanks, Stalin simply grumbled, "Lazar, put it back."

Today, St. Basil's stands as a museum and UNESCO World Heritage site, attracting millions of visitors who take millions of nearly identical photos. It represents the fusion of religious, political and architectural history, or as the Russians call it, "Tuesday."

To the northwest of St. Basil's looms Spasskaya Tower, the Kremlin's main entrance and the tower with the famous clock. Built in 1491 by Italian architect Pietro Antonio Solari, it was originally called Frolovskaya Tower until they stuck an icon of Jesus above the gate and renamed it "Savior's Tower."

| Tower | Built | Height (with Star) | Star Installed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spasskaya Tower | 1491 | ~71 m | 1937 |

| Nikolskaya Tower | 1491 | ~70 m | 1937 |

| Troitskaya Tower | 1495 | ~80 m | 1937 |

|

|

Spasskaya Tower, Moscow Kremlin Spasskaya Tower: Russia's fanciest doorbell. The clock has survived fires, revolutions and bad timekeeping. The star on top replaced a double-headed eagle in 1937. |

The icon led to the tradition of men removing their hats while passing, which was basically 16th - century Russia's version of "no shirt, no shoes, no service." Tsars, foreign dignitaries and now tourists all enter through this gate, though the tsars probably didn't have to go through metal detectors.

|

|

Saint Basil's Cathedral, Red Square Moscow's dynamic architectural duo. One says 'pray here,' the other says 'power here.' Together they say 'tourist photos here.' |

During Soviet times, Spasskaya Tower became the backdrop for military parades where they showed off missiles that may or may not have actually worked. The clock chimes every 15 minutes and plays the Russian national anthem on the hour, which is either patriotic or annoying depending on how close you're trying to sleep.

Standing at 71 meters tall, Spasskaya Tower is crowned with a ruby - red star added during the Soviet era. The star replaced the double - headed eagle, because nothing says "workers' paradise" like a giant illuminated star hoisted up by heavily sweating steeplejacks.

The Kremlin’s ruby stars replaced the imperial double - headed eagles in 1935, with illuminated ruby - glass versions installed in 1937. Each star uses layered ruby glass panels on a metal frame with internal lighting. The replacement of the imperial eagles with Soviet stars is well documented in official historical records.

The tower's design merges medieval Russian defensive elements (thick walls, arrow slits) with Italian Renaissance aesthetics (ornate spires, detailed brickwork). It's basically a fortress that went to art school.

Spasskaya Tower has witnessed everything from Napoleon's invasion to World War II victory parades. Today it stands as a historic gem that represents Russian endurance, mostly endurance of really long lines to get into the Kremlin.

Lenin's Not-So-Final Resting Place

Further along the Kremlin wall stands Lenin's Mausoleum, where Vladimir Lenin has been on display since 1924. The mausoleum is made of red granite, porphyry and black labradorite, which sounds like materials for a villain's lair but was actually quite fashionable in 1930s funeral architecture.

Lenin's body has been preserved through a secret Soviet embalming process that involves baths in special chemicals roughly every 18 months. The exact formula is still a state secret, though rumor says it involves equal parts science and stubbornness. During World War II, they evacuated Lenin's body to Tyumen in Siberia for safekeeping, which must have been awkward for everyone involved.

Next to the mausoleum stands Senatskaya Bashnya (Senate Tower), built in 1491 by the same Italian architect as Spasskaya Tower. It's named after the nearby Senate Palace, which is now the Russian President's office. The tower represents traditional Russian defensive architecture, which basically means "thick walls, small windows and don't even think about invading."

Standing there, showed us a city of layers - medieval walls next to Soviet monuments next to capitalist shops. It felt like a historical lasagna, if lasagna was made of brick, slogans and extremely confident vodka.

But our Moscow travel adventure was just beginning. We still had to check out the metro system properly, try real borscht and figure out how to buy a metro ticket without accidentally purchasing a dacha. We soon descend into Moscow's underground palaces and discover that Russian subway stations are fancier than most people's houses. But before that, we could not help but check out a few more places.

Continuing our drizzle - soaked stroll along Red Square for our Moscow sightseeing, we reached the Nikolskaya Tower, which guards the Kremlin's eastern flank with the quiet dignity of a bouncer who's seen too many invasions to be impressed anymore. Built in 1491 by Italian architect Pietro Antonio Solari, the tower got its name from the nearby St. Nicholas Monastery that apparently couldn't afford better real estate.

The red brick walls of the modern Moscow Kremlin were rebuilt between 1485 and 1495 under Ivan III, with several Italian architects including Pietro Antonio Solari involved in the project. Renaissance engineering met Russian ambition and the result still runs the skyline.

Here's a piece of history most guidebooks skip: During the intense fighting of the 1917 October Revolution, the tower took severe artillery damage. When the smoke finally cleared, Moscow discovered that the mosaic icon of St. Nicholas above the gate had miraculously survived the bombardment largely untouched, peering out from a heavily blasted brickwork frame.

The tower's 70 - meter height makes it perfect for spotting tourist groups before they become your problem. It survived everything from Polish incursions to renovations, proving that good Italian architecture is like a well - made pasta - it holds up under pressure.

Just past the tower at Red Square's northern end stands the State Historical Museum, which looks like a tsar's fever dream of what a museum should be. Founded in 1872 and completed in 1883, it was Russia's way of saying, "We have history too and we're putting it all in one very red building."

Peter the Great didn't trust dentists. He'd yank teeth himself - sometimes from his own mouth, sometimes from his courtiers for practice. He even kept a personal collection of extraction tools that looked more suited for medieval torture than dental work. Those instruments eventually ended up in the Kunstkamera museum in St. Petersburg, where visitors can still see 'teeth pulled out by Peter the Great himself' on display.

Inside, they've crammed everything from Scythian gold to Soviet propaganda posters. One obscure exhibit features 19th - century merchant account books showing they spent more on tea than on building maintenance. Some things never change.

The collection spans 4 million items, including Ivan the Terrible's actual throne (reportedly uncomfortable) and Catherine the Great's coronation carriage (reportedly very comfortable). The Soviet section has the original draft of the Five - Year Plan with handwritten notes like "add more steel" and "fewer holidays."

On Red Square's east side stands GUM, the shopping mall that makes your local mall look like a sad garage sale. The name stands for "Glavnyi Universalnyi Magazin," which translates to "Main Universal Store" or "Place Where Your Rubles Go to Die."

Built between 1890 and 1893 by architect Alexander Pomerantsev, GUM became engineering wizard Vladimir Shukhov's structural masterpiece. His glass roof design was so revolutionary that other architects accused him of witchcraft. The roof uses 20,000 glass panes and apparently zero bird deterrents, based on the evidence.

Here's a grounding piece of reality: When the foundations were dug for the building, construction workers unearthed the ancient remains of Moscow's original commercial trading rows. This real estate has essentially functioned as the city's marketplace for centuries. Some things are simply eternal in Russian commerce.

GUM has more historical identities than a Cold War spy. It opened as a department store, became Stalin's office space (imagine buying socks where five - year plans were drafted) and returned to retail after the USSR collapsed. The 1990s renovation cost $200 million, which is approximately one million Soviet - era Lada cars.

Today, GUM houses luxury brands that cost more than the average Russian annual salary. You can buy a Gucci bag where Soviet citizens once queued for basics. Historical irony comes with free air conditioning.

While most visitors ogle the glass roof, the operational history of GUM during the Soviet era is a a sign of bureaucratic endurance. Rather than running like a precise military operation, it functioned under the vast, lumbering apparatus of the Ministry of Trade. Behind the grand façade, store managers constantly wrestled with the same supply shortages that plagued the rest of the command economy, making the presence of goods on the shelves a minor daily miracle.

|

|

Inside GUM, Moscow More GUM interior views. Those glass canopies have seen more economic systems than a university textbook. The perfect place to practice looking rich while being tourist-broke. |

During the decades of chronic shortages, GUM also harbored one of Moscow's worst - kept secrets: Section 200. This was a completely unmarked, closed - door department store hidden within the main building, exclusively serving the highest echelons of the Soviet elite. While everyday citizens queued for basic boots, the nomenklatura shopped for imported French perfume and tailored suits out of public view. You didn't just need money to shop there; you needed a very specific Communist Party card.

Beyond shopping, hosts cultural exhibitions that have included everything from fashion retrospectives to modern art installations. For us tourists, it was more than a mall - it was a time machine with exceptional heating. We wandered beneath that glass canopy, marveling at how history and commerce have learned to coexist.

Red Square Panoramas: Because One Angle Wasn't Enough

We captured some 360 - degree panoramas of Red Square because regular photos weren't sufficiently immersive. These stitch jobs show the square in all its rainy glory.

|

|

Red Square 360 panorama, Moscow Red Square panorama that required standing in the rain for 10 minutes. Shows everything from Lenin's Tomb to tourist umbrellas. |

Creating wide panoramas of carries its own modern bureaucratic irony. While tourists freely snap wide - angle photos on smartphones, attempting to use professional photographic equipment - specifically a tripod - requires a formal permit from the Federal Protective Service (FSO). We made do with handheld sweeps, contending only with the drizzle and the odd pigeon.

The resilience of these stones is a point of local pride. While they look like they’ve been there since the dawn of time, they are actually a 1930s upgrade designed to handle the crushing reality of Soviet parades. They provide a reliable, if somewhat unforgiving, surface for everything from military hardware to the millions of tourist footsteps that wear down everything except the stones themselves.

|

|

Red Square west panorama, Moscow Western view showing the Kremlin wall practicing its stoic expression. The State Historical Museum trying to out-red everything else. |

Moscow Metro Sightseeing: Where Stalin Meets Subway

Next morning, our second day in Moscow before boarding the Trans - Siberian Railway, we returned to Moscow's Metro system. Because when in Russia, do as Russians do: go underground and marvel at socialist realism.

The Moscow Metro opened on 15 May 1935 with 13 stations. As of January 2026, it has 304 stations and is the busiest metro system in Europe. It moves millions daily and somehow still finds time to look like a palace.

The streets radiating from Red Square carry their own political baggage. Nikolskaya Street, right off the square, was rebranded as "Street of the 25th of October" in 1935 to honor the Bolshevik Revolution. Meanwhile, the famous Tverskaya Street was renamed after writer Maxim Gorky. Eventually, both reverted to their historical names after the Soviet collapse. The moral? You can rename a street, but you can't rename the people's memory.

The Moscow Metro opened on May 15, 1935, with exactly 13 stations and has since expanded to a massive subterranean network carrying roughly 9 million people daily. It was Stalin's pet project to prove that socialism could build prettier, grander transit hubs than capitalism.

We started at Metro Paveletskaya, conveniently located near our hotel and a Czech brewery. Because nothing says "Russian subway experience" like starting with European beer.

|

|

Metro Paveletskaya station entrance, Moscow Paveletskaya station entrance with a bonus Czech brewery. Because Russian subways apparently need beer accompaniment. |

Little - known fact: The early Metro was not built by prisoners in secret, as is often rumored. It was a highly publicized prestige project utilizing enthusiastic Komsomol (Communist Youth) volunteers, specialized miners imported from the Donbas and highly paid laborers. It was the absolute centerpiece of 1930s Soviet propaganda.

The 's deepest station is Park Pobedy, which goes an astonishing 84 meters underground - deep enough to qualify as geological exploration. While that specific station was built in 2003, many of the older, deeper central stations were designed with a dual purpose in mind: to double as massive bomb shelters during the Cold War. Because nothing says "surviving nuclear war" like waiting it out beneath marble columns.

Trains arrive every 90 seconds during peak hours, which is more frequent than most people's good ideas. The system is so punctual that Muscovites set their watches by it. Late trains are considered unpatriotic.

If you’re wondering why the “mind the closing doors” voice suddenly changed gender, it’s not the Metro gaslighting you. The Moscow Metro uses male voices for trains heading toward the city center and female voices for trains heading out toward the suburbs. On the circular Koltsevaya line, the masculine voice announces the clockwise route, while the feminine voice handles the counter - clockwise. It’s a handy navigation cue - and a gentle reminder that Moscow always has a plan for where you should be going.

Paveletskaya Station Sightseeing: Where Lenin Took the Train

Paveletskaya Metro Station opened in 1943, right in the middle of World War II. Because when Nazis are at your gates, what you really need is a beautifully decorated subway station. Priorities.

The station serves both the Zamoskvoretskaya and Koltsevaya lines, making it a hub for people who can't decide which line to take. Its tall white marble pillars were quarried from the Urals.

Paveletskaya station was built during World War II and the marble for its columns was taken from a church that had been damaged in the war. The Soviet authorities saw it as recycling; the church saw it as sacrilege. The columns still bear faint traces of Orthodox crosses, which the station cleaners were ordered to scrub off but never quite managed to erase.

The station was designed by renowned Soviet architects Alexey Dushkin and Nikolai Knyazev. The design is genuinely Soviet, specifically representing a transition between Art Deco and the heavier Stalinist Empire style that would come to dominate later constructions.

The mosaics at Paveletskaya were created by artists utilizing the same ideological techniques and color palettes found in prominent propaganda posters. The figures in the mosaics look like they're about to march off the wall and start a revolution, rendered with strictly accounted - for materials under intense state supervision.

Paveletskaya hooks directly into the Paveletsky Rail Terminal, making it a transit hub for anyone catching trains south toward the Volga region.

Taganskaya Station Sightseeing: Military Parade Underground

Taganskaya Metro Station opened in 1950 and looks like what would happen if a military parade had a baby with a palace. Located on the Circle Line, it's Stalinist architecture at its most confident.

The station features arched niches with reliefs of soldiers from different branches - infantry, navy, air force and cavalry. They all share the same determined expression, perfectly suited for the rigid demands of Stalinist architecture.

|

|

Taganskaya Metro Station interior, Moscow Taganskaya interior where marble meets military precision. Architecture designed to make waiting feel historically significant. |

The real drama during Taganskaya's construction wasn't archaeological, but geological. Engineers had to battle intense subterranean water pressure and complex soil conditions to hollow out this massive underground space, relying on advanced deep - level freezing techniques to stabilize the earth before they could even begin laying the marble.

|

|

Taganskaya Metro Station interior details, Moscow More Taganskaya architectural overachievement. The majolica panels were crafted with steady hands and ideological commitment. |

Taganskaya station takes its name from the Taganka district, which historically housed craftsmen making tagany (iron trivets used for cooking over open fires). The area was famous later for the notorious Taganka Prison, but the prison was several blocks away and wasn't demolished until 1958, meaning it posed zero obstacle to the station's 1950 construction.

Those ornate chandeliers hanging above the platform are purely decorative, crafted from ornate brass and glass. They are not military - grade hardware designed to withstand shockwaves, despite the station's depth and structural integrity.

|

|

Taganskaya Metro Station architecture, Moscow Final Taganskaya view before moving to the next underground palace. The architecture whispers "Soviet power" while shouting "look at these tiles!" |

Komsomolskaya Station: The Underground Palace

Komsomolskaya Metro Station is what happens when you give an architect unlimited marble and tell them to impress visiting foreigners. Opened in 1952, it's Stalinist Baroque at its most baroque.

Designed by architect Alexey Shchusev, the station connects three major railway stations: Leningradsky, Yaroslavsky and Kazansky. It's essentially Grand Central Station's more dramatic Russian cousin.

Vagabond Tip For long - distance trains at Yaroslavsky Station, arrive early. Passport checks and platform screenings are routine. Build in buffer time.

The intricate mosaics adorning the ceiling do contain actual gold leaf, fused between layers of glass to create the brilliant smalt tiles. This immense attention to luxurious detail was specifically intended to project the power and triumph of the Soviet state to the thousands of travelers arriving from the regions every day.

The artwork, designed by Pavel Korin, depicts Russian military heroes like Alexander Nevsky and Dmitry Donskoy looking appropriately heroic. Historical accuracy regarding armor and weaponry was largely ignored in favor of dramatic lighting and maximum patriotic impact.

|

|

Komsomolskaya Metro Station interior, Moscow Komsomolskaya's vaulted ceilings practicing their dramatic curves. Perfect for looking upward while avoiding eye contact with other commuters. |

The red granite and light marble that forms the backbone of the station's massive colonnades were transported from the Ural Mountains, requiring an immense logistical effort utilizing the standard Soviet industrial rail network to bring the raw materials to the capital for finishing.

Komsomolskaya

The station's massive chandeliers are a product of changing times. They were originally designed to be lit by gas, but the plan was switched to electricity late in the process. The obsolete gas pipes were simply capped off inside the ceiling infrastructure, serving as a hidden reminder of the era's rapid technological shifts.

The story of workers cleaning the ceiling frescoes with a mixture of vodka and distilled water is a delightfully Russian myth. In reality, the Soviet maintenance crews relied on standard, entirely un - drinkable industrial conservation materials to keep the artwork pristine.

Another popular piece of Cold War paranoia suggests the marble columns are hollow to hide security services listening devices. The reality of physics dictates otherwise: these columns are solid structural necessities holding up thousands of tons of earth and concrete. Surveillance existed, but it didn't compromise the structural integrity of public transit hubs.

The flooring is dominated by red and pink granite originally sourced from the Shoksha quarry. Rumors that Ukrainian granite had to be hastily replaced by slightly mismatched Ural granite after the 1991 Soviet collapse are unfounded; the floor's color palette was a deliberate design choice from day one.

|

|

Komsomolskaya Metro Station interior, Moscow More Komsomolskaya views from different angles because one wasn't enough. The station design makes utilitarian transportation feel like a cultural event. |

Komsomolskaya was the final masterpiece of architect Alexey Shchusev. He was not, as some guides claim, fired for going 200% over budget and defending "beauty." In fact, Shchusev was a highly decorated architect who died in 1949. The station was completed posthumously in 1952, standing as a final monument to his vision.

The station takes its name from the Komsomol, the All - Union Leninist Young Communist League. During the grueling manual construction of the first Metro lines in the 1930s, thousands of young Komsomol volunteers provided the essential labor. The name remains an enduring tribute to them.

There is a persistent myth that the station's clocks were originally set permanently to the time of the October Revolution. They were not. From day one, the clocks were calibrated to standard Moscow time, ensuring the relentless punctuality of the Soviet commuting machine.

|

|

Komsomolskaya Metro Station interior, Moscow More Komsomolskaya architectural excellence for your viewing pleasure. The mosaics depict Russian military history with artistic interpretation. |

The materials utilized to build Komsomolskaya were sourced via the standard, albeit massive, industrial supply lines of the Soviet Union. The wood, marble and granite arrived not through poetic coincidence, but through highly coordinated state extraction efforts.

Looking at Komsomolskaya, you’d think it was built slowly and politely. In reality, engineers were dealing with tricky ground and heavy city load above. They used a “pioneer trench” approach: carve narrow side corridors first, brace them, then dig out the big central hall. It’s basically building the closets first and hoping the roof stays friendly while you add the living room.

While the deeper stations in the network were heavily reinforced to function as civil defense shelters during the Cold War, the massive air circulation systems were primarily installed for a much simpler reason: keeping millions of commuters from suffocating on stale, subterranean air.

Komsomolskaya stands exactly as its architects intended: a subterranean cathedral of marble and light, engineered to assure the Soviet citizen that the state possessed both the power to move them and the wealth to awe them.

KomsomolskayaSovietMoscow sightseeing

As we emerged from each of 's underground palaces, we realized the isn't just transportation - it's the city's subconscious, decorated with marble mosaics of its aspirations. Each station tells a story of a nation that believed even subway stops should be extraordinary, making our experience truly unforgettable. But we still have a couple of more metro stations to check out and continue on.

Novoslobodskaya: Moscow's Underground Stained-Glass Cathedral

We rolled into Novoslobodskaya station and immediately felt underdressed. This isn't a subway stop; it's a subterranean art gallery that forgot to charge admission. Opened in 1952 on the Circle Line, it was the pet project of Alexey Dushkin, who apparently decided that commuters deserved more than just damp tunnels and flickering lights.

The stunning stained glass windows were designed by Russian artist Pavel Korin but were manufactured in Riga by Latvian artisans. This wasn't a sneaky workaround; Riga possessed a centuries - old tradition of master glasswork, making it the only logical place within the Soviet sphere to execute such intricate designs. The panels are set into heavy, elaborate brass frames that anchor the station's aesthetic.

|

|

Novoslobodskaya Metro Station, Moscow Each panel portrays idealized figures of Soviet society - architects, musicians, agronomists - framed by complex floral and geometric motifs. |

The word "МИР" (Peace/World) glows at one end of the platform. It's a nice sentiment, though the original 1952 plan was less about peace and more about a certain mustachioed leader. That end - wall mosaic originally featured a prominent profile of Joseph Stalin. After his death and the subsequent de - Stalinization campaigns, the mosaic was quietly reworked. The dictator was erased, replaced by soaring white doves and the word 'Peace'. Thank goodness for small mercies.

Architecturally, this Moscow metro station is a masterclass in illusion. It is a deep - level pylon station, meaning massive, thick columns hold up the earth above. To counteract the heavy, oppressive feeling of these structural necessities, the architects used the illuminated stained glass and high, arched ceilings to trick the brain into perceiving airy, cathedral - like space. The circular, conical light fixtures suspended from the ceiling were designed to cast a diffuse, forgiving glow.

The layout, with two rows of columns holding up the sky - or at least several tons of soil and infrastructure - is meant to impress and intimidate and it succeeds wildly. You half - expect a choir to start singing every time a train arrives.

|

|

Novoslobodskaya Metro Station, Moscow Close-up of one of the Latvian-made stained glass panels. The glass is layered, creating a depth and richness of color that demands close inspection. |

The panels were painstakingly crafted in Riga by artists E. Veylandan, E. Krests and M. Ryskin. They utilized colored glass that had been sitting unused in the stores of the Riga Cathedral. By repurposing this high - quality material based on Korin's strict Soviet ideological sketches, they achieved the brilliant, luminous effect that defines the station.

|

|

Novoslobodskaya Metro Station, Moscow Another panel, featuring complex geometric patterns framing the central figures. The heavy brass frames complete the illusion of heavy, opulent antiquity. |

The brass frames themselves require significant upkeep. While not polished daily, the maintenance crews carefully manage the metal to ensure it retains its characteristic dull, golden gleam without tarnishing completely under the damp subterranean conditions.

Novoslobodskaya station

|

|

Novoslobodskaya Metro Station, Moscow Detail of the white Ural marble cladding on the pylon columns. The natural veining of the stone provides a subtle counterpoint to the bright colors of the glass. |

The construction of deep - level stations like Novoslobodskaya was a monumental engineering feat, relying heavily on the grueling labor of thousands of workers to excavate the earth and pour the concrete before the fine marble finishing could even begin.

Like all major Soviet transit hubs, the flooring was designed with practicality in mind from the beginning. The honed, slip - resistant finish of the granite was a vital safety requirement to prevent the station from turning into a dangerous ice rink during the brutal Moscow winters.

Korin's dedication to quality is evident in the materials used for the end - wall mosaic. He utilized high - grade, traditionally fired smalti (glass paste colored with metallic oxides) to ensure the mural's brilliance would not fade over the decades, creating a piece of state propaganda built to outlast generations.

The lighting fixtures were specifically engineered by the Metro Design Bureau to combat the gloom of deep - level transit. The frosted glass panels were custom - manufactured to diffuse the harsh electric bulbs, bathing the station in a softer, more even light that complements the glowing stained glass rather than competing with it.

|

|

Novoslobodskaya Metro Station, Moscow The junction where marble wall meets granite floor, demonstrating crisp Soviet craftsmanship. |

The structural integrity of these deep stations is immense. Far from slowly sinking into the earth, as urban legends sometimes claim, the massive concrete and cast - iron tubings forming the station's shell are rigidly locked into the stable geological strata far beneath the Moscow water table.

Belorusskaya: A Moscow Metro Station That's Basically a Palace for Belarus

|

|

Belorusskaya Metro Station, Moscow Belorusskaya's Circle Line platform, opened in 1952. The design is a monumental love letter to the Soviet Republic of Belarus. |

If Novoslobodskaya is a cathedral, then Belorusskaya station is the royal palace. This station on the Circle Line is a monument to Soviet Belarus, primarily because it sits directly beneath the Belorussky Railway Station, the historical gateway for trains heading west to Minsk and Europe.

Designed by the husband - and - wife architectural team of Ivan Taranov and Nadezhda Bykova, the station opened in 1952. They went all out. The ceiling is a masterwork of plaster that would give a Renaissance artisan pause. The massive chandeliers are custom - designed statements of imperial weight, assembled from heavy crystal and brass specifically to anchor this grand subterranean space.

|

|

Belorusskaya Metro Station, Moscow The ornate ceiling stucco work, featuring heavy floral and agricultural motifs. |

The ceiling stucco work in the Belorusskaya metro heavily utilizes traditional Belarusian national patterns, intertwining geometric borders with lush wreaths of wheat and flora, intended to symbolize the agricultural abundance of the republic.

|

|

Belorusskaya Metro Station, Moscow One of the decorative panels depicting Belarusian folk life. The abundant wheat sheaves are a classic staple of Soviet pastoral fantasy. |

The panels lining the ceiling vault are executed in the classic Soviet realist style, deliberately emphasizing healthy, smiling faces and massive harvests to project an idealized vision of the collective farming system across the Soviet republics.

|

|

Belorusskaya Metro Station, Moscow A mosaic panel showing an idealized Belarusian scene. The vibrant colors are achieved using smalti glass tiles, a technique dating back to Byzantine times. |

In recognition of its intense historical and artistic value, Belorusskaya - along with several other masterwork stations on the Circle Line - was eventually added to Russia's Unified State Register of Cultural Heritage Sites, cementing its status as a nationally important architectural monument.

|

|

Belorusskaya Metro Station, Moscow The grand central hall with its soaring, structural arches supporting the station box. |

The white marble pillars lining the hall are clad in stone from the Koelga quarry in the Urals, a primary source for many of the most important Stalin - era monuments and buildings across the capital.

|

|

Belorusskaya Metro Station, Moscow A final detail of the massive chandeliers, custom-designed to bring imperial weight and warm light to the deep-level platforms. |

The intricate wiring of these fixtures ensures the station is never plunged into darkness, a critical safety feature built into all deep - level stations operating far from natural light.

|

|

Belorusskaya Metro Station, Moscow A bas-relief celebrating Belarusian industry. The workers look determined and vaguely happy, as was the mandated artistic style at the time. |

The central hall feels like a ballroom. The arches are tall enough to fit a double - decker bus and the floor is a mix of red and grey granite. It's a space specifically scaled to make the individual feel small and the state feel overwhelmingly large. We half - expected to see a red carpet and a receiving line.

The darker Zamoskvoretskaya Line platform is a study in architectural contrast. Opened before the war, it features heavy columns clad in deep red Shrosha marble quarried in Georgia, accented with black gabbro. It lacks the flamboyant, triumphant agricultural themes of the 1952 Circle Line hall, standing instead as a more somber, serious predecessor.

|

|

Belorusskaya Metro Station, Moscow Dark red Shrosha marble columns on the older platform. The brass accents are minimal but perfectly polished, reflecting a more austere pre-war design aesthetic. |

Belorusskaya (Circle Line) opened on 30 January 1952 and it briefly served as a terminus before the Ring Line was completed in 1954. We love a station that can move commuters and flex at the same time.

|

|

Belorusskaya Metro Station, Moscow A final look at the majestic Circle Line hall. It's a transport hub, an art gallery and a political statement all in one. |

The Koltsevaya (Ring) Line opened in stages from 1950 to 1954 and the 1952 expansion brought the ring up to Belorusskaya. We appreciated the design logic: fewer center - city transfers, less human pinball.

|

|

Belorusskaya Metro Station, Moscow The exit towards Belorussky Railway Station. The signage is classic Soviet metro style - clear, bold and no-nonsense. |

Belorusskaya station

Belorussky Train Station: Where the Imperial Era Meets the Rails

|

|

Belorussky Train Station, Moscow The grand facade of Belorussky Station in its green-and-white imperial livery. It was built between 1909 and 1912, just before the Romanov dynasty crumbled. |

Emerging from the metro, we were greeted by the Belorussky Railway Station, a neoclassical confection in green and white. This isn't just a transit hub; it's a time capsule from the last days of the Russian Empire. Designed by architect Ivan Strukov, it was built in a style meant to project the enduring power of an empire that was, in reality, on the brink of collapse.

Historically the gateway to Smolensk, Minsk, Warsaw and Berlin, the station served as a crucial hub for military transport during World War I. In the Soviet era, it was renamed "Belorussky" to emphasize the connection to the Belarusian SSR. The station has watched Tsars depart, Soviet armies march to the front and modern tourists arrive.

.JPG)

|

|

Belorussky Train Station, Moscow The exterior architecture features prominent Empire-style elements, with the green facade providing a stark contrast to the heavy stonework. |

Inside, the main hall is a vast, vaulted space designed to handle massive flows of international and domestic passengers. The station also houses a small, dedicated museum of railway history, preserving artifacts from the golden age of Russian rail travel.

|

| Belorussky Train Station |

Kievskaya: A Moscow Metro Station Built on Friendship (With Benefits)

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow The grand entrance to Kievskaya station on the Circle Line. Opened in 1954, it was heavily championed by Nikita Khrushchev to celebrate Russo-Ukrainian unity. |

Our next stop was Kievskaya station, another Circle Line beauty. Opened in 1954, its lavish design was intended to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the 1654 Treaty of Pereyaslav, which brought Ukraine under Russian protection. This Moscow metro station is a stunning example of late Stalinist Empire style, designed by a team of architects including Yevgeny Katonin.

The station is a visual feast of marble, mosaics and gold. The central hall is flanked by heavy pylons, each adorned with a large mosaic panel set within an ornate, gilded stucco frame. The color scheme is warm beige and gold, creating a deliberately opulent feel meant to project agricultural and cultural wealth.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow One of the 18 main mosaic panels depicting idealized scenes of Ukrainian life, agriculture and historical unity with Russia. |

The vibrant mosaics in Kievskaya were executed using high - quality smalti glass. The artists utilized hundreds of distinct shades to achieve the painterly realism and rich, varying hues required by the strict dictates of the Socialist Realism style.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow The ornate white and gold arches framing the mosaics. The intricate stucco borders feature genuine gold leaf applied to emphasize the station's importance. |

The intricate ornamentation surrounding the mosaics represents a deliberate stylistic shift. While earlier stations focused on sleek lines or raw industrial power, Kievskaya embraces a heavily decorated, almost baroque aesthetic intended to project total national prosperity.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A mosaic of a Ukrainian woman holding wheat, a classic symbol of Soviet agricultural abundance. |

The mosaic artists relied on rigorous preliminary sketches to capture the idealized forms required by Socialist Realism. The goal was never strict photographic accuracy, but rather the projection of a healthy, triumphant and fully integrated citizenry.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow Another mosaic panel showing Cossacks, the legendary warriors of the steppe, represented here to emphasize historical ties to Moscow. |

The station features floral patterns explicitly inspired by traditional Ukrainian folk embroidery, a subtle nod to the culture woven throughout the broader political messaging. It was named using the standard Russian spelling of the era, standing as a permanent record of 1950s geopolitical staging.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow The coffered ceiling, an ancient architectural technique used to significantly reduce the weight of the massive vault overhead without compromising structural strength. |

The ceiling design serves a highly practical function. By recessing large sections of the plaster vault (coffering), the engineers reduced the dead load pressing down on the station's supporting columns, a technique dating back to the Roman Pantheon.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A mosaic depicting the heavy industrialization of Ukraine. Factories, dams and determined workers - the Soviet dream executed in smalti glass. |

Kievskaya station is a masterpiece of Soviet design, but it's also an inescapable political artifact. It represents a highly specific era in the USSR's internal relations. Today, that symbolism carries a heavy historical weight, but the artistic craftsmanship required to build the station remains undeniable. We admired the execution while pondering the complexities of history.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow The grand arches and columns of the central hall. The floor pattern, executed in highly durable granite, provides visual guidance through the massive transit space. |

The granite flooring was installed with extreme precision, designed to withstand the daily abrasion of millions of commuters over decades of continuous use without losing its structural integrity or visual appeal.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A mosaic framing traditional floral motifs. These decorative borders are essential in tying the disparate historical scenes together into a cohesive visual narrative. |

Every visual element in the station was vetted by a central artistic committee. They ensured that traditional cultural symbols, like specific floral arrangements or embroidery patterns, were appropriately aligned with the state's broader secular and ideological messaging.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow Another view of the mosaic gallery along the platform. The repeating arches create a steady architectural rhythm that draws you down the length of the station. |

Because smalti glass is incredibly tough and non - porous, the mosaics require very little specialized maintenance. Standard cleaning procedures are sufficient to remove the accumulation of brake dust and subterranean grime.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A mosaic showing an idealized Soviet cityscape. The architecture in the background reinforces the narrative of continuous, state-driven progress. |

Every scene was meticulously planned by the artistic committee to ensure it aligned perfectly with the overarching theme of Russo - Ukrainian historical unity, leaving nothing to individual artistic interpretation.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A detail of the ceiling stucco and one of the smaller chandeliers. |

The stucco relief work required an immense amount of skilled labor to complete before the station's grand opening. Utilizing specialized plaster mixtures, artisans worked continuously on scaffolding high above the platform floor to sculpt the intricate borders that frame the station's central mosaics.

The lighting system in this Moscow metro station was designed to overcome the inherent gloom of deep - level transit. The use of elaborate, multi - tiered chandeliers rather than utilitarian industrial fixtures was a deliberate choice to elevate the space from a mere tunnel to a public reception hall.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A mosaic capturing the dynamic movement of a traditional Ukrainian folk dance, celebrating the cultural heritage of the republic. |

The artists employed by the state architectural bureau worked from carefully composed preliminary sketches to ensure that every aspect of the mosaics - from the folds of the traditional clothing to the expressions on the dancers' faces - met the strict ideological requirements of the era.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow The geometric floor pattern constructed from highly durable red and grey granite, designed to withstand the wear of millions of daily footsteps. |

The flooring was sourced from various active quarries across the Soviet Union. The primary goal was to lay down a surface that could handle the immense, grinding foot traffic of a major transit hub without cracking or requiring constant replacement.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A close-up of the gold leaf detailing on the stucco arches framing the mosaics. The ornamentation was considered a necessary expense for a showcase station. |

The application of gold leaf in these stations wasn't an afterthought; it was a fundamental part of the design philosophy. The state was willing to expend significant resources to ensure the architecture projected an image of absolute, unshakable prosperity to its citizens.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A mosaic depicting a historical meeting commemorating the Treaty of Pereyaslav, the central theme of the station's artwork. |

This particular mosaic serves as the historical anchor for the entire station. It illustrates the 1654 treaty that brought the Cossack Hetmanate under the protection of the Russian Tsar, a defining moment utilized by 1950s Soviet leadership to emphasize an unbroken lineage of unity.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A detail showing the intricate stucco rosettes decorating the ceiling vault. The sheer scale of the plasterwork required immense skilled labor. |

The artisans responsible for the stucco work labored extensively to cast and install these heavy decorative elements. The repetitive, intricate patterns serve to draw the eye upward, reinforcing the grand, airy illusion of the deep subterranean hall.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A mosaic heavily emphasizing agricultural abundance, reinforcing Ukraine's historical role as the breadbasket of the USSR. |

These depictions of overflowing harvests were a central tenet of Socialist Realism. They were designed not to reflect the immediate reality of the era's collective farms, but rather to project the state's vision of an inevitable, bountiful socialist future.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow The exit escalator hall, featuring a more restrained but still elegant design compared to the main platform. |

The massive escalators required to reach these deep stations are engineering marvels in their own right. Moving thousands of passengers an hour up to the surface requires heavy - duty mechanical systems that are continuously maintained and periodically completely rebuilt.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow A final mosaic showing an idealized vision of harmony. The artwork remains a beautiful, highly polished fossil of a specific political era. |

Every piece of art in the station was executed to meet the exacting standards of the state. The artists operated within strict thematic boundaries, utilizing their mastery of the smalti medium to fulfill the ideological commissions assigned to them.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow One last look down the majestic platform of Kievskaya station. It's a place where monumental art, high politics and public transit collide spectacularly. |

We spent a long time at Kievskaya station, just as we did at the other Moscow metro stations. The network isn't just a way to get around; it's a massive, deeply ideological subterranean museum. Every station tells a story of the era in which it was built. With our feet tired and our camera cards full, we finally headed back to the surface, ready for the next chapter of our Moscow travel adventure.

|

|

Kievskaya Metro Station, Moscow The station name sign, a classic of Soviet typography. The heavy, backlit brass lettering was designed to project permanence, outlasting the ideology that put it there. |

Ploschad Revolyutsii: Moscow's Bronze Hall of Heroes

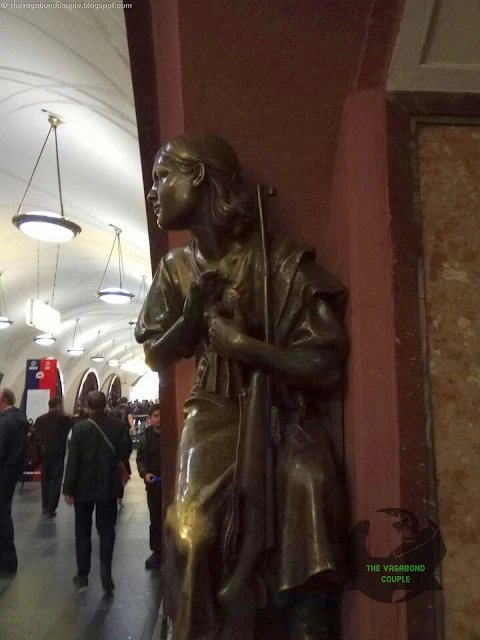

We descended into what felt like a Soviet - era sculptural fortress. Isn't just a transport hub - it's a 1938 time capsule where 76 bronze statues judge your commute. Architect Alexey Dushkin designed the sleek red and black marble arches, but he reportedly hated the statues, feeling they crowded and compromised his clean architectural lines. The political committee overruled him, demanding the space serve as a gallery of the new Soviet citizen.

The station opened on March 13, 1938, a masterpiece of subterranean engineering. Like all deep - level stations in central Moscow, it required massive, active drainage systems to keep the surrounding water table at bay, ensuring the bronze heroes remained dry.

|

|

Ploschad Revolyutsii Metro Station, Moscow Soviet realism up close and personal. This student looks like he's about to ace his exams on dialectical materialism. |

During World War II, this deep station served a vital secondary purpose as an air - raid shelter. Thousands of Muscovites slept on the platforms between these bronze heroes while the city was bombed above. The statues themselves represent a deliberate political timeline, charting the evolution of the Soviet citizen from the armed revolutionaries of 1917 to the peaceful students and farmers of the late 1930s.

|

|

Ploschad Revolyutsii Metro Station, Moscow The red marble arches create perfect frames for the Soviet heroes. Each niche feels like a stage waiting for its bronze actor to begin a speech. |

Sculptor Matvey Manizer, backed by a massive state commission, created the statues at the Leningrad Monumental Sculpture Factory. Because the niches Dushkin designed were relatively low, Manizer had to pose his figures sitting, kneeling, or crouching, which paradoxically gave them a sense of coiled, dynamic energy.

The most famous statue features a frontier guard with his dog. For decades, a superstition has held that rubbing the dog's nose brings good luck, particularly for university students facing exams. The nose is now burnished to a bright, golden shine by millions of hopeful hands. It has become such an ingrained Moscow tradition that transit officials actively maintain the polished state of the bronze.

There are only 20 distinct designs among the 76 statues; the figures repeat as you move down the platform. This repetition was deliberate, reinforcing the idea of a unified, collective mass rather than celebrating unique individualism.

|

|

Ploschad Revolyutsii Metro Station, Moscow The proletariat in permanent bronze overtime. This worker's hammer has also been highly polished by thousands of passing commuters. |

The black marble forming the base of the arches provides a stark contrast to the red. Material sourcing was a major logistical operation for the Ministry of Railways, coordinating shipments of specific stone types from quarries deep in the Urals and Karelia to fulfill the rigid architectural demands of the capital.

|

|

Ploschad Revolyutsii Metro Station, Moscow The station's massive structural columns. Every architectural choice carried ideological weight in 1938, designed to project permanence and strength. |

We spent an hour wandering this underground gallery. The statues are highly detailed, capturing specific uniforms, weapons and tools relevant to the late 1930s. The sailor's uniform matches the fleet designs of the era and the athlete's pose echoes contemporary Soviet sports posters. Manizer succeeded in creating a literal time capsule of Stalinist ideals.

|

|

Ploschad Revolyutsii Metro Station, Moscow A Red Army soldier standing eternal guard underground. The base has worn smooth from decades of subway vibrations and foot traffic. |

As we rode the escalator up, we realized Ploschad Revolyutsii represents a fascinating contradiction. It celebrates revolution through rigid permanence and people's power through top - down state control. The station has long outlived the Soviet Union it glorifies and the bronze heroes continue their silent vigil as Muscovites rush past, pausing mostly just to rub a lucky dog's nose.

Emerging into rainy Moscow felt like time travel from 1938 to 2017. We walked down Nikolskaya Street, which has its own deep history. Beneath the modern boutiques lies the old road leading toward the Nikolsky Monastery area. The street was historically a center of education and printing and it later became part of Moscow’s early push into gas and electric street lighting. Revolution Square above us has seen everything from medieval markets to revolutionary speeches to modern protests.

We passed over the - or rather, where it flows underground. In medieval times, this open waterway acted as a moat for the Kremlin but eventually became an open sewer for the city's tanners and butchers. Following the devastating 1812 fire, Alexander I's urban planners enclosed the river in a three - kilometer brick tunnel to create the Alexander Garden. Modern Muscovites can still occasionally hear the rushing water through grates during heavy rains, a ghost river reminding them of what flows beneath.

|

| Ploshchad Revolyutsii Metro Station, Moscow |

Resurrection Gate: Moscow's Rebuilt Memory

Voskresenskiye Vorota

The gate survived the 1812 French occupation but couldn't survive Soviet modernization. In 1931, Stalin's planners demolished the entire structure because military parades needed wider access into Red Square. The irony? Those parades celebrated revolutionary victory while destroying revolutionary - era architecture.

|

| Ploshchad Revolyutsii Metro Station, Moscow |

The 1995 reconstruction faced a problem: nobody had complete original blueprints. Architects used pre - 1931 photographs, paintings and architectural surveys. The new gate isn't identical - it's slightly narrower because modern utilities run beneath. But it captures the spirit. The double - headed eagles were recreated using 17th - century patterns found in museum archives.

|

| Ploschad Revolyutsii Metro Station, Moscow |

Iverskaya Chapel: Moscow's Spiritual Doorman

The original Iveron icon arrived from Mount Athos in 1648. For centuries, it was customary for anyone entering Red Square - including the Tsars - to stop and pray before it. The Soviet demolition of the chapel in 1929 wasn't simple vandalism; it was a calculated move to erase religious focal points while clearing space for military parades. The original icon was confiscated by the state and its current location remains unknown.

|

| Ploshchad Revolyutsii Metro Station, Moscow |

Today's chapel is a 1994 reconstruction. The new icon is a 1995 copy, freshly painted and blessed on Mount Athos to replace the lost original. Purists may note it's not the 17th - century artifact, but most Muscovites are simply glad to have their spiritual doorman back.

|

|

Proyezd Voskresenskiye Vorota Passage, Moscow The passage where medieval met modern Moscow. Rain makes the cobblestones shine like they're freshly laid. |

We watched pilgrims and tourists mingle at the chapel. An old babushka crossed herself three times before entering Red Square. A Japanese tour group snapped photos. The gate and chapel create a perfect Moscow microcosm - faith, history, commerce and tourism all squeezed into one rain - dampened space.

|

|

Resurrection Gate and Iverskaya Chapel, Moscow The perfect Moscow postcard view, stitched from multiple shots. Resurrection Gate frames the chapel like a jewel in an architectural setting. |

Resurrection Gate (also called the Iberian Gate) is the only surviving gate of old Kitay - gorod. The Soviet government demolished the gate in 1931 and it was rebuilt in 1994–1995, which is Moscow’s way of saying, “Fine, we missed it.”

Manezhnaya Square: Where History Gets a Makeover

We turned toward Manezhnaya Square, named for the Moscow Manege riding school built in 1817. The square has been rebuilt so many times it's basically Moscow's architectural Etch A Sketch. The original 19th - century square held markets and public gatherings. Stalin added grandiose plans that never fully materialized. The 1990s reconstruction created the massive underground shopping mall that locals call "the bunker."

|

|

Resurrection Gate and Iverskaya Chapel, Moscow The gate's perfect symmetry satisfies obsessive-compulsive architects. Raindrops collect on the eagles like tiny liquid jewels. |

The square's modern centerpiece is the World Clock Fountain, a massive glass dome that slowly rotates to indicate the time across the Northern Hemisphere. It sits atop the massive Okhotny Ryad underground shopping mall, a multi - level subterranean labyrinth built in the 1990s as Moscow aggressively embraced modern capitalism.

|

|

Manezhnaya Square toward Red Square, Moscow Manezhnaya Square spreads out like Moscow's living room. The massive Hotel Moskva (now a Four Seasons) dominates the left side of the frame. |

Marshal Zhukov's monument commands the space in front of the State Historical Museum. The 1995 statue shows the famed Soviet commander on horseback, mirroring the iconic imagery of the 1945 Victory Parade. The monument's location sparked intense debate at the time of its installation; some wanted it placed directly on Red Square, while others felt an equestrian military monument was too aggressive for the immediate shadow of the Kremlin walls.

Zhukov's legacy is complicated, spanning absolute triumph over Nazi Germany to his controversial role in suppressing the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. The monument deliberately captures him at his absolute zenith in 1945. Local guides have started a tradition of telling tourists that rubbing the horse's hoof brings luck, a practice that has noticeably polished the bronze over the decades.

|

|

Manezhnaya Square Overview, Moscow Manezhnaya Square's vast, open expanse, dominated by the World Clock dome marking the subterranean entrance to the Okhotny Ryad mall. |

Looming over the square is the Four Seasons Hotel, a modern hotel that reopened in 2014 behind a facade that echoes the old Soviet - era Hotel Moskva. The original Hotel Moskva was demolished in 2004 and the current exterior keeps the famous “two different wings” look. A popular Moscow legend blames that asymmetry on Stalin signing between two design options; in real life, the story is debated, but the lopsided look is very real.

Alexander Garden: Moscow's Green Drawing Room

Aleksandrovsky Sad feels like Moscow's front lawn. Architect Osip Bove designed it as part of the massive reconstruction effort following the 1812 fire and the expulsion of Napoleon's army. To create the park, Bove had the heavily polluted Neglinnaya River diverted into an underground pipe and used soil from the Kremlin moat excavations to level the ground. He embedded subtle monuments to the victory over the French throughout the park, including a grotto built from the rubble of Moscow buildings destroyed during the occupation.

|

|

Kremlin Walls in Rain, Moscow The formidable red brick walls of the Kremlin provide a stark, dramatic backdrop for the meticulously manicured gardens below. |

The garden is traditionally divided into three sections: Upper, Middle and Lower. It was designed primarily as a public promenade for Moscow society, giving citizens a structured, elegant green space directly beneath the seat of imperial - and later Soviet - power.

|

|

Alexander Garden, Moscow Alexander Garden's manicured perfection. Every flower bed is arranged with absolute precision, maintained by a dedicated army of city landscapers. |

Beneath the manicured lawns of the Alexander Garden flows the Neglinnaya River, which was forced into a brick tunnel in 1819 to prevent it from flooding the Kremlin walls. The river, once a vital defense moat, now exists as a subterranean rumor, audible only through the occasional manhole cover to those with particularly sensitive ears or a lack of better hobbies.

"The Bolshoi Theatre was rebuilt after the fire of 1853 by the architect Alberto Cavos... He was particularly concerned with acoustics and used resonant pine for the walls."

Caroline Brooke, Moscow: A Cultural History (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 158. ISBN 978-0195309522.

The massive bronze horse fountain dominating the edge of the park is part of the artificial Neglinnaya River installation created by sculptor Zurab Tsereteli in the 1990s. The four horses represent the four seasons, galloping powerfully through the engineered waterway.

|

|

Four Seasons Fountain, Alexander Garden, Moscow Tsereteli's horses gallop through the artificial riverbed. The water splashes mimic hooves striking the earth in heavy, bronze slow motion. |

The “Four Seasons” fountain on Manezhnaya Square/Alexander Garden is a modern landmark: the horse sculpture is by Zurab Tsereteli and the fountain opened in 1996. We watched it do its thing and understood why Moscow likes its public art with extra horsepower.

|

|

Four Seasons Fountain Alternate View, Moscow The horses seem to leap from the water. Each season represented is cast with a distinct muscular tension. |

Kremlin's Middle Arsenal Tower: The Watchful Guardian

Srednyaya Arsenal'naya Bashnya (The Middle Arsenal Tower) has the grim distinction of being bombed by Napoleon's troops. In 1812, retreating French soldiers exploded the Kremlin's nearby Arsenal building, severely damaging the tower in the process. Reconstruction took until 1819. The tower's current appearance dates to that repair, though its foundations remain rooted in the 15th century. It earns its straightforward name because it stands squarely between the Corner Arsenal and Trinity Towers.

|

|

Four Seasons Fountain Details, Moscow Water and bronze in perpetual motion. The massive sculptures are a modern addition to a park deeply rooted in 19th-century history. |

Nearby, housed within the building, lies the Diamond Fund, a staggering collection of state jewels initiated by Peter the Great. It houses artifacts of immense historical weight, including the famed 189.6 - carat Orlov Diamond. Count Grigory Orlov purchased the legendary gem - which was as the story goes stolen from a Hindu temple in India - and presented it to Catherine the Great in a futile attempt to win back her romantic favor. It now sits permanently in the Imperial Scepter.

Vagabond Tip In 2017, the Kremlin Armoury ran timed entry tickets. Buying online or arriving at opening time reduces the chance of sold - out midday slots.

|

|

Srednyaya Arsenal'naya Bashnya and Grotto Ruins, Moscow The grotto's deliberate, romantic decay contrasts sharply with the Middle Arsenal Tower's sheer defensive solidity. |

Lining the walls of the nearby Arsenal building are rows of captured cannons, silent trophies of failed invasions. The collection includes hundreds of French pieces abandoned during Napoleon's disastrous 1812 retreat, as well as older Swedish guns captured by Peter the Great during the Great Northern War, serving as a heavy metal timeline of Russian military history.

|

|

Kremlin Arsenal Building, Moscow The Arsenal's severe, utilitarian facade. Captured cannons line up like metallic trophies, a visual warning to anyone eyeing the Kremlin walls. |

Grotto Ruins: Moscow's Most Romantic Rubble

Joseph Bove's 1821 Grotto Ruins is a classic example of romantic 19th - century landscaping. Rather than importing fresh stone, Bove deliberately utilized actual fragments from Moscow houses destroyed in the 1812 fire, embedding genuine historical trauma directly into the city's new pleasure garden.

|

|

Grotto Ruins, Alexander Garden, Moscow Artfully arranged destruction as a garden feature. The grotto stands as a monument to Moscow's fiery resilience. |

During the 19th century, the grotto wasn't just a quiet spot to reflect; the structure above it frequently served as a bandstand where military orchestras played for the strolling public, blending imperial military culture seamlessly with civic leisure.

Romanov Obelisk: History's Footnote

The Romanovskiy obelisk has had a severe identity crisis. Originally erected in 1914 to celebrate 300 years of the Romanov dynasty, it lasted barely four years before the Bolsheviks stripped the imperial names and replaced them with a list of socialist thinkers and revolutionary leaders in 1918. It stood as a Soviet monument until 2013, when it was dismantled and entirely rebuilt to restore its original 1914 imperial design.

|

|

Romanovskiy Obelisk, Alexander Garden, Moscow The obelisk stands tall, a physical manifestation of Russia's rapidly shifting historical narratives over the last century. |

Nearby stands the modern monument to Patriarch Hermogen, erected in 2013. The statue honors the religious leader who famously starved to death in a Kremlin dungeon rather than submit to occupying Polish forces during the Time of Troubles in 1612. The monument represents modern Russia's concerted effort to resurrect and celebrate pre - Soviet orthodox figures.

.jpg)

|

|

Monument to Patriarch Hermogen, Moscow Hermogen stands defiant in bronze. His cross faces the Kremlin as both a challenge to invaders and a historical blessing. |

After his death in 1612, Hermogenes' body remained in the Chudov Monastery until 1652, when Patriarch Nikon moved it to the Dormition Cathedral with full honors. There it rested undisturbed until 1913, when workers accidentally uncovered his original crypt during repairs at the Chudov Monastery. The timing coincided perfectly with the Romanov Dynasty Tercentenary, leading to his canonization that same year.

|

|

Monument to Patriarch Hermogen Alternate View, Moscow Details reveal the modern sculptor's skill. Hermogen's robes fall in heavy, realistic bronze folds, anchoring the figure to the base. |

Kutafiya Tower: The Kremlin's Chubby Gatekeeper