72 Hours in Peru - The Land of the Inca | Cusco & Sacred Valley: Písac, Urubamba, Ollantaytambo, Machu Picchu

|

|

Manco Cápac: first governor and founder of the Inca civilization in Cusco

By Cusco School - Unknown source, Public Domain, Link

|

Let me tell you a story that's more epic than any Netflix series. Once upon a time, around 1200 AD (give or take a century), the Sun God Inti and Moon God Mama Quilla looked down from the heavens at the primitive humans living around Lake Titicaca. These folks were basically cave-dwelling hunter-gatherers with zero culture - no agriculture, no cities, not even decent pottery. The divine couple had enough of this uncivilized nonsense and decided to send their son Manco Cápac and daughter Mama Ocllo on a divine intervention mission. Their task? Bring law, order, and civilization to these hapless humans. Before sending them off, Inti gave Manco a golden staff called the tapac-yauri with instructions that sounded like ancient GPS: "Use this to find fertile land and set up a kingdom."

Now here's where it gets interesting - Manco and Ocllo didn't just appear out of thin air. They emerged from a netherworld cave called Pacaritambo, which according to legend was located at Tambotoco hill. Imagine their arrival - two divine beings showing up in what's now southern Peru, probably scaring the daylights out of the locals. But they came bearing gifts: civil order, education, arts, and religion (specifically worship of the Sun and fire as gods). They were basically the original cultural ambassadors, teaching people how to use fire (finally, cooked food!), tools, weapons for self-defense, cultivation techniques (bye-bye, hunter-gatherer lifestyle), and textile production (fashionably late to civilization).

Depiction of Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo, the legendary founders of the Inca civilization, teaching the people of the Andes.

The legend of Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo isn't just a bedtime story - it's what anthropologists call a "foundation myth." Similar to Romulus and Remus for Rome, this story gave the Inca Empire its divine right to rule. What's fascinating is how it reflects actual historical processes. Scholars believe this myth encodes the migration of the Inca people from the Lake Titicaca region to the Cusco Valley around the 12th century. The "golden staff" might symbolize advanced agricultural knowledge - finding land where crops would grow well in the challenging Andean environment.

While Mama Ocllo stayed to teach the women textile arts and domestic skills (she's basically the patron saint of ancient Peruvian homemaking), Manco embarked on an epic journey across the Andes. He trekked through mountains and valleys looking for the perfect spot to plant his kingdom. After what must have been months of hiking at altitudes that would leave modern tourists gasping for oxygen, he came across a remarkably beautiful valley. He thrust the tapac-yauri into the ground, and it sank easily - the divine sign he'd been waiting for. Right there, he built his city, calling it Cusco (or Qosqo in Quechua, meaning "navel of the world"). The Kingdom of Cusco was thus established with Manco Cápac as the first Sapa Inca (Supreme Leader).

Eventually, Manco and Ocllo had a son named Sinchi Roca who would become the Second Sapa Inca. Now here's a fun fact that sounds like something from Game of Thrones: Manco Cápac reportedly had 400 children to carry on his bloodline before he died. That's either divine fertility or some serious creative accounting by Inca historians! Cusco's Temple of the Sun called Coricancha (Temple with Golden Walls) marks the location of Manco's passage into the underworld. His mummified remains were later moved from Cusco to the Temple of the Sun on Isla del Sol by the outstanding 9th Sapa Inca Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui. A statue of Manco was instead erected in Cusco.

There are various, some of them incompatible, versions of this legend of origin of Manco Cápac and the kingdom of Cusco. Some versions say he emerged from Lake Titicaca itself. Others claim there were actually four brothers and four sisters who founded Cusco. It's even possible Manco Cápac didn't actually exist but is a product of mythology cooked up by later Inca rulers to legitimize their rule. But here's what's undeniable: the layers of stone walls at the bottom of buildings on narrow stone alleys still present in Cusco and the jaw-dropping ruins of Inca complexes that we visited away from the city remain a testament to the heights the Inca civilization reached in just over three hundred years before being snuffed out by invading and destructive Spaniards.

The 9th Sapa Inca Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui was another towering figure in Inca history. As we would learn in Pisac, Pachacuti was the emperor who annexed territory and people outside the Kingdom of Cusco to transform the kingdom to an empire. The city complexes of Pisac, Ollantaytambo and Machu Picchu are among those built by Pachacuti as he expanded the empire. It is believed Pachacuti is buried under the Temple of the Sun at Machu Picchu.

The theme of Spanish destruction of a people and civilization that was at the time far advanced and richer than their own resonated in our minds throughout our entire time in the incredible country of Peru. It's heartbreaking when you realize that the Spaniards melted down gold artifacts not for their monetary value but because they considered Inca art "idolatrous." They literally turned centuries of artistic achievement into boring gold bars.

A Country in Violent Socio-Political Unrest

Protesters gathering in Lima during the December 2022 political unrest in Peru.

The image above shows a scene that became all too familiar in late 2022 - thousands of Peruvians taking to the streets in what would become the most significant political crisis since the fall of Alberto Fujimori in 2000. The protests weren't just in Lima; they spread across the country, particularly in southern regions with large Indigenous populations. What started as political maneuvering in the capital quickly became a national uprising with deep roots in Peru's historical inequalities.

We traveled to Peru during a period of violent political protests. Tourists had to be evacuated by helicopter just two days ago as the country devolved into massive demonstrations, roadblocks, airport, train and road closures. Injury and death tolls of protestors in the forceful government response at the hands of riot police and military forces were mounting. There were news reports of stranded American tourists at Machu Picchu hiking over 32KM along rail tracks to reach helicopter extraction points.

On December 7, 2022, President Pedro Castillo was about to be impeached for the third time when he announced plans to dissolve Congress and install an emergency government, put the country under curfew, suspend and rewrite the constitution and hold fresh elections. Peru’s Ombudsman described this as an “attempted coup d’état.” (CNN). The Peruvian Congress responded by removing and arresting Castillo sentencing him to 18 months of pre-trial detention on rebellion charges. President Dina Boluarte took over with approval of the Congress. Supporters of ousted Castillo, especially among indigenous Peruvians in southern Peru with affiliation to the political left and far-left, felt disenfranchised and organized to protest against the ouster and detention of Castillo, demanding resignation of the new President Boluarte and Castillo's reinstatement. President Boluarte's government reacted by deploying armed forces and Peruvian police whose aggressive actions continue to result in injuries and death. As I write this, protestors are attempting to "take over" the capital city of Lima!

I was continuously in touch with Incarail and we owe our fortuitously successful visit to them. Their advice for us was that there would be a break in protests and trains would run over the Christmas and New Year holidays, that they had repaired the sabotaged tracks, and that our trip with Incarail on December 23-24 was on.

On the positive side, this meant we had the rare opportunity of being among only a handful of visitors and the only hotel guests at places that ordinarily draw 7,000 tourists every day! Imagine having Machu Picchu almost to yourself - that's like finding a parking spot in Manhattan during Christmas season!

During our brief stay in Peru (we left for Bolivia on December 25), we learned from multiple locals that the demonstrations would start back up on January 4, 2023. This indeed turned out to be true. As of Jan 13, 2023 Peru had officially declared emergency with curfews in effect and Cusco airport and train station closed with all tourism suspended.

Here is a complete map of our expedition to Peru.

December 21, 2022

We took a Uber to BWI and boarded a series of Delta and LATAM flights starting 19:39 to reach Cuzco the following morning (December 22) 10:05 with transfers at Atlanta and Lima.

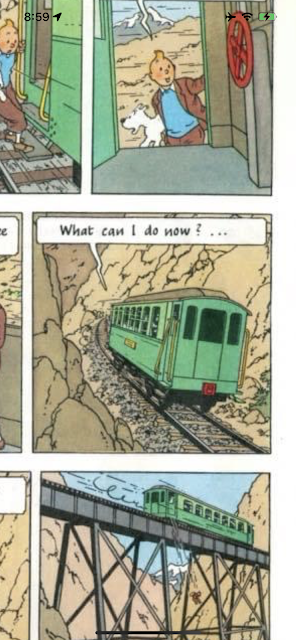

I put my new mobile phone camera stand to test at the BWI airport. It came with a bluetooth remote for remote triggering the camera. We were going to the land where Tintin's adventures of the Seven Crystal Balls and the Prisoners of the Sun were set, making a photo with Tintin comics imperative to mark the start of our journey!

BWI Airport terminal at the start of the journey to Peru.

Tintin comic book "The Seven Crystal Balls" open to a page showing Tintin boarding a train to Peru.

For those who didn't grow up reading Tintin like I did, "The Seven Crystal Balls" and "Prisoners of the Sun" form one of the most iconic adventure stories set in Peru. Belgian cartoonist Hergé (Georges Remi) published these in the 1940s, and despite never having visited Peru himself, he managed to capture the Western imagination of the country perfectly. The stories mix Inca mythology, mummies, and adventure in a way that inspired generations of Europeans to visit Peru. The comics are surprisingly well-researched for their time, drawing on published accounts of Inca civilization.

The flights were uneventful. The Starbucks at Lima airport with Inka chips and Inka corn were refreshing.

Starbucks coffee shop at Lima Airport.

Inka Fries and Inka Corn snacks purchased at Lima Airport.

Those "Inka chips" and "Inka corn" at Lima Airport Starbucks aren't just marketing gimmicks - they're part of Peru's incredible agricultural heritage. Peru is the birthplace of the potato (over 3,000 varieties!), tomatoes, peppers, and countless other crops. The "Inka corn" you see is probably choclo, the large-kernel corn that's been cultivated in the Andes for millennia. It's not as sweet as North American corn but has a unique flavor and chewy texture that's perfect for snacks.

December 22, 2022

Cusco, Peru (13.5° S, 71.9° W, altitude 11,152 feet)

Summer Solstice in Southern Hemisphere!

We landed at Alejandro Velasco Astete Cusco International Airport (CUZ) in a miraculous lull in the middle of Peru's political turmoil and violent demonstrations. The airport was closed only a couple of days before but was reopened with strong military presence just before we arrived. Peru's security forces in military fatigues and automatic weapons welcomed us to the baggage carousel at the eerily empty airport, from where we had to walk out to the outside gates at the boundary walls on Av. Velasco Astete. Only ticketed passengers were being allowed in and out, on foot, from the external gate.

Exterior view of Alejandro Velasco Astete International Airport in Cusco.

Baggage claim area at Cusco Airport with military personnel present.

Passengers walking from the airport to the external gate on Avenida Velasco Astete.

That altitude number isn't a typo - Cusco sits at a breathtaking 11,152 feet (3,399 meters) above sea level. To put that in perspective, that's higher than most ski resorts in the Rockies. The air has 30% less oxygen than at sea level, which explains why perfectly healthy people sometimes feel like they're having a heart attack after climbing a flight of stairs. The airport is named after Alejandro Velasco Astete, a Peruvian pilot who was the first to fly across the Andes - a feat that cost him his life when he crashed near Cusco in 1925.

The driver of our hotel-transfer minivan was standing with a placard outside on Av. Velasco Astete. We walked a couple of blocks pulling our luggage to an alley where he asked us to wait while he went away to fetch his minivan from wherever he was parked at.

Street scene in Cusco near the airport with Andean mountains in the background.

Those mountains in the background aren't just pretty scenery - they're the Andes, the world's longest continental mountain range, stretching over 4,300 miles along South America's western coast. What's geologically fascinating is that the Andes are still growing - they're being pushed up by the Nazca Plate diving beneath the South American Plate at about 2-3 inches per year. That might not sound like much, but over millions of years, it creates mountains that literally touch the sky.

He arrived with the minivan around 15 minutes later and we successfully checked in to Yawar Inka Hotel. I had carefully selected this hotel for its location: three minutes walk to Estacion Wanchaq from where the Perurail Titicaca train to Puno is boarded (though we would not get to board that train), and fifteen-minute walk along the arterial Av. El Sol to Plaza de Armas - the colonial central plaza of Cuzco.

We were the only guests at the hotel, that too on the first day of Santurantikuy!

View from the hotel room in Cusco showing traditional architecture.

Interior courtyard of Yawar Inka Hotel in Cusco.

Street view near the hotel in Cusco showing colonial buildings.

The architecture you see in these photos is a fascinating mix of Inca foundations and Spanish colonial style. After the Spanish conquered Cusco in 1533, they did something clever (or arrogant, depending on your perspective): they built their churches and palaces right on top of Inca temples and palaces. This served two purposes - it used the existing stonework (which was better than anything the Spanish could build), and it symbolically demonstrated Spanish dominance over Inca religion and culture. The red-tiled roofs are a Spanish introduction - the Incas used thatched roofs.

Coca Tea

We had the first of endless cups of Coca Tea at the hotel. Considered sacred from ancient times by folks of the Andes, Coca leaves induce biochemical changes that enhance physical performance at high altitude. Chewing Coca leaves is rampant in the Andes, and is considered addictive and responsible for long black hair common among indigenous people.

Cup of Coca tea, a traditional Andean drink for altitude acclimatization.

Let's talk about coca tea, because there's so much misunderstanding about it. First, it's not cocaine - it's tea made from the leaves of the coca plant. The cocaine alkaloid is just one of many compounds in the leaf, and you'd need to process kilograms of leaves with chemicals to get any significant amount of cocaine. What coca tea does contain is mild stimulants that help with altitude sickness - it dilates blood vessels, improves oxygen uptake, and gives you a gentle energy boost. The Incas considered coca sacred - they called it "the divine plant" and used it in religious ceremonies. Today, it's as common in the Andes as coffee is in America. And no, it won't make you fail a drug test unless you drink about 50 cups in an hour.

Yellow Fever Vaccination in Cusco, Peru

International Certificate of Vaccination for Yellow Fever obtained in Cusco.

Many countries require an International Certificate of Yellow Fever Vaccination for entry. Cusco is one the places where this vaccine is easily obtained. I had set up an appointment with Inmuno Farma for our family of four. They offer the convenience of coming to the hotel to vaccinate and issue official international certification. A very nice nurse and a gentleman arrived at our hotel punctually, vaccinated us with Stamaril, and gave us our certificates. It was a nice and smooth experience with no discernible side effects later. Even with the on-location service, the vaccines cost us a fraction of the money charged by travel clinics in the United States. Inmuno Farma are highly recommended (I am not affiliated with them, this is an independent opinion).

Yellow fever might sound like something from a 19th-century novel, but it's still very real in parts of South America. The vaccine is required because yellow fever can spread rapidly in tropical areas. Interestingly, the vaccine we got (Stamaril) is made using chicken embryos - a method developed in the 1930s that's still used today. The certificate we received is sometimes called the "yellow card" and is recognized worldwide. Without it, countries like Bolivia (our next destination) can deny entry or quarantine you.

Walking around Cusco

The location of Cusco has been continuously inhabited by humans for at least 3,000 years making it one of the oldest living cities in the Americas. The city flourised as capital of the Inca Empire of Cusco (c.1200 - 1533 CE) till the Inca civilization was destroyed when Spaniards invaded. The original main plaza was constructed by founding Inca emperor Manco Cápac. Unfortunately little of Cusco's original Inca complex survives, having been overlaid with typical Spanish architecture and cathedrals which I have little interest in. As we would see shortly, only a few stone foundations and streets built by the Incas are still visible in Cusco.

Our hotel doors lead out to the wide Av. Pardo Paseo de los Héroes - a wide boulevard with a median but with huge gaping utility construction holes allowing only pedestrians navigating carefully around the mostly unmarked excavations. There are statues along the median and important looking villas, one with security forces guarding it two houses down from the hotel. It will look awesome when all the construction is over.

Avenida Pardo Paseo de los Héroes in Cusco under construction.

Statue on the median of Avenida Pardo in Cusco.

That statue on Avenida Pardo is probably of a Peruvian hero from the War of the Pacific (1879-1884) or possibly from the struggle for independence. Peru has a complex history of statues - many Spanish colonial statues were torn down after independence, replaced by heroes of the republic. More recently, some statues have become flashpoints in political protests. The construction you see is part of Cusco's eternal struggle to modernize while preserving its UNESCO World Heritage status. Every time they dig, they find Inca ruins, which stops construction for archaeological assessment.

View down Avenida Pardo showing colonial-style buildings.

Another section of Avenida Pardo with utility work ongoing.

The first right on Av. Garcilaso gets us to the arterial Av. El Sol. Taking a left on El Sol, we crossed a post office (Serpost - Servicios Postales del Perú) to reach Jardín Sagrado (Sagrado Garden). It is a large green garden where events are held, at the time featuring a pretty Christmas tree with decorations. There is a convenient ATM at the corner of the post office from which I withdrew some Peruvian Sol cash.

Serpost (Peruvian Postal Service) office in Cusco.

ATM machine on Avenida El Sol in Cusco.

Pro tip for travelers: Those ATMs are your best friend in Peru. Credit cards are accepted in tourist areas, but cash is king everywhere else. The Peruvian Sol (PEN) has been surprisingly stable in recent years. When I visited, the exchange rate was about 3.8 Sol to the US dollar. And yes, those ATMs sometimes charge fees, but they're usually lower than currency exchange offices. Always choose to be charged in local currency rather than dollars to avoid dynamic currency conversion scams.

Avenida El Sol, one of the main arteries in Cusco.

|

| View down Avenida El Sol towards the city center. |

|

| Buildings along Avenida El Sol with Andean hills in the background. |

As a proud Hughes Network Systems alumnus, I was happy to see a HughesNET advertisement on Av. El Sol. I had no idea Hughes provides satellite internet services in Peru. There was also a facebook expresswifi advertisement, but I am not sure what that service is.

Advertisement for HughesNet and Facebook Express WiFi on a building in Cusco.

Internet in the Andes is a modern miracle. HughesNet provides satellite internet to remote areas where laying cables would be impossible (or prohibitively expensive) due to the mountainous terrain. Facebook's Express WiFi is a program that helps local entrepreneurs set up affordable WiFi hotspots in their communities. What's fascinating is how technology is leapfrogging in Peru - many remote villages have WiFi before they have reliable running water.

Behind Jardín Sagrado, noticing still-visible remnants of Inca stone structures below typical Spanish buildings, we make a right towards them on C. Arrayanniyoq (Route 3S). Crossing the Iglesia y Convento de Santo Domingo de Guzmán (Convent of Santo Domingo) we walk the narrow alley to Plazoleta Santo Domingo featuring Limacpampa.

Jardín Sagrado (Sacred Garden) in Cusco with a Christmas tree.

The current Santo Domingo plaza area was the grand central square of Inca capital Cusco where the Coricancha ("Golden Walls") temple stood representing full glory of the empire. It featured at the minimum walls covered with gold and a golden statue of Sun God Inti covered with jewels. Having set out but failed to destroy all of Coricancha, the Spaniards appropriated the stupendous volume of gold and jewels, even melting the statue of Inti. Then they built a Christian Convent of Santo Domingo on top of the remnants of Coricancha using material from the destroyed Coricancha. The original Spanish convent did not last long, falling apart in an earthquake in 1650. The current structure was then constructed to replace it, this one losing its bell tower and chapel in the earthquake of 1950 requiring re-rebuilding.

Convent of Santo Domingo, built on the foundations of the Inca Coricancha temple.

The earthquake history here is important. Peru sits on the Pacific Ring of Fire, where tectonic plates collide, causing frequent earthquakes. The Incas built their structures to withstand earthquakes using trapezoidal doors and windows, inward-leaning walls, and interlocking stones without mortar. Spanish architecture, with its straight walls and heavy roofs, didn't fare as well. It's poetic justice that the Spanish buildings kept falling while the Inca foundations remained intact.

The narrow alleys around the convent seem to continue the pattern of Spanish construction over older Inca foundations displaying a level of stone construction much beyond the capabilities of the Spaniards. The alleys themselves look like Inca pathways, perhaps with water channels in the middle.

Traditional Peruvian restaurant "Romeritos" in a Cusco alley.

Side view of the Convent of Santo Domingo showing Inca stonework at the base.

Narrow alley (Calle Arrayanniyoq) in Cusco with Inca stone walls visible.

That Inca stonework is mind-blowing when you really look at it. The stones fit together so perfectly that you can't slip a credit card between them. And they did this without metal tools, without the wheel, and without mortar. How? They used stone hammers (harder stones to shape softer ones), sand for polishing, and probably a lot of trial and error. Some stones have as many as 12 angles that all fit perfectly with neighboring stones. It's like a 3D puzzle that's survived earthquakes for 500+ years.

On reaching Plazoleta Santo Domingo, we make a right on Av Tullumayo.

Plazoleta Santo Domingo square in Cusco.

Avenida Tullumayo, a street in central Cusco.

Local shops and buildings along Avenida Tullumayo.

From a tiny Claro mobile phone store there, we buy a SIM with a ridiculously cheap prepaid data plan probably in the range of S/10.00 for 750MB for five days plus S/5.00 for the SIM itself! We were asked for our passport details to make the purchase. Fortunately I had a photo of my passport on my phone, which was sufficient.

Small Claro mobile phone store in Cusco.

Claro is one of Latin America's largest telecom companies, originally part of Mexico's América Móvil. The requirement to show your passport for a SIM card is Peru's attempt to combat crime and terrorism - all SIMs must be registered to a real person. This practice started after the Shining Path terrorist group used unregistered phones in the 1990s. Today, it's just a minor inconvenience for tourists that helps authorities track criminal activity.

We also picked up some toiletries (toothbrush, toothpaste, deodorant) for the boy from a small general store next to the mobile shop before heading back to Av. El Sol.

Small general store (tienda) in Cusco selling daily necessities.

These small family-run stores are called "tiendas" and are the backbone of Peruvian neighborhood commerce. They're usually just the front room of someone's house converted into a shop. You can find everything from snacks to toiletries to basic groceries. Unlike supermarkets, prices aren't marked, so you have to ask. They're great places to practice your Spanish and get a feel for local life.

In the evening, we headed out again towards Plaza de Armas. The streets were slightly less deserted and a few fellow tourists could be seen now. Holiday lights turned on at dusk. The majestic Palacio de Justicia, Consultorio Juridico Gratuito UNSAAC, Museo de Arte Popular and surrounding buildings along Av. El Sol leading to Basilica Menor de la Merced and Plaza de Armas looked festive indeed, though police in riot gear were guarding the steps of the Cusco Palace of Justice. We picked up cappuccino and ice cream on the way from one of the cafes along Av. El Sol.

Avenida El Sol in Cusco at dusk with holiday decorations.

Jardín Sagrado illuminated with Christmas lights in the evening.

Palacio de Justicia (Palace of Justice) in Cusco.

Close-up view of the Palacio de Justicia facade.

The Palacio de Justicia (Palace of Justice) is where Peru's judicial system operates in Cusco. The riot police presence during our visit was directly related to the political crisis. Courthouses became targets for protesters angry about what they saw as judicial persecution of Pedro Castillo. Ironically, the building itself represents the Spanish colonial legal system imposed on Peru, which has always had a complex relationship with indigenous concepts of justice.

Avenida El Sol at night with lit buildings.

Night view of Avenida El Sol with traffic and pedestrians.

Building along Avenida El Sol decorated with Christmas lights.

Evening scene on Avenida El Sol with historic architecture.

Colorful mantas (blankets) displayed near Basilica Menor de la Merced in Cusco.

Those colorful textiles aren't just for tourists - they're part of a weaving tradition that dates back thousands of years in the Andes. Each pattern, color, and design has meaning, often indicating the wearer's village, marital status, or social position. The "mantas" (blankets) are typically made from alpaca or sheep wool and dyed with natural colors from plants, minerals, and insects. What looks like simple geometric patterns often encodes complex cosmological concepts or stories from Andean mythology.

Santurantikuy - The Famous Arts and Crafts Fair at Plaza de Armas, Cusco

Panoramic view of the Santurantikuy arts and crafts fair at Plaza de Armas in Cusco.

From December 22 to 24 every year, Cusco's famous Plaza de Armas (Cusco Main Square) transforms into a giant arts and crafts fair called the Santurantikuy. A tradition from the 16th century, it is one of the largest fairs in Peru where local artisans set up rows of stalls selling authentic hand-crafted artefacts. In addition to bringing festive Christmas spirit, a mind-boggling array of hand-carved figurines of San José, Virgin Maria and Niño Manuelito along with Andean handicrafts were on sale. Vendors around also sold Christmas-special sweets and the warm rum punch called ponche. We were fortunate enough indeed to experience Santurantikuy.

The name "Santurantikuy" comes from Quechua and Spanish words meaning "saint for sale." It began after the Spanish conquest as a way for indigenous artisans to create Christian religious figures using their traditional techniques. Over time, it evolved into this massive festival. The figurines are particularly interesting - they blend Catholic iconography with Andean features and symbolism. The "Niño Manuelito" (Baby Jesus) often has indigenous facial features and is sometimes depicted with Andean animals.

I also got to play with an Alpaca!

Vendor stall at Santurantikuy fair selling traditional nativity figurines.

Alpaca next to artisan selling hand-carved wooden figurines at Santurantikuy.

Alpacas! These adorable camelids are more than just cute photo ops. They've been domesticated in the Andes for over 6,000 years. Their wool is lighter, warmer, and less itchy than sheep's wool. Alpacas come in 22 natural colors, which is why you see so many different shades in Peruvian textiles. They're also environmentally friendly grazers - they have soft padded feet that don't damage grasslands like hooved animals do. And yes, they do spit when annoyed, but usually at each other, not tourists.

Crowd browsing handicrafts at the Santurantikuy fair in Plaza de Armas.

Colorful textiles and crafts on display at a Santurantikuy stall.

Wide shot of Santurantikuy fair with stalls lining the plaza.

Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús (Church of the Society of Jesus), located in the Plaza de Armas in Cusco, Peru.

That magnificent church in the background is the Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús, built by the Jesuits in the 17th century on the palace of Inca Huayna Cápac. It's considered one of the best examples of Spanish Baroque architecture in the Americas. The Jesuits were expelled from Peru in 1767, but their church remains. During earthquakes, the plaza has been used as a refuge - its open space is safer than being near buildings.

Vendor arranging nativity scene figurines at her stall.

Traditional Peruvian dolls and toys for sale at Santurantikuy.

Petting an alpaca at the Santurantikuy fair in Cusco.

And then, back to the hotel.

Night view of Cusco's illuminated streets and buildings.

Cusco at night is magical. The city lights illuminate the colonial architecture while the surrounding mountains loom dark against the starry sky. At this altitude, the stars are incredibly bright - you can see the Milky Way clearly on moonless nights. The Incas were master astronomers who built their cities aligned with celestial events. Cusco itself was laid out in the shape of a puma, with Sacsayhuamán forming the head. At night, you can almost feel the ancient energy of the place.

December 23, 2022

The first of our memorable two-day one-night IncaRail Machu Pichu multimode (van, train, bus) tour from Cusco.

A nice gentleman representing the tour met us at 7:25 AM sharp at our Cusco hotel. We gulped down Coca tea, left all of our luggage at the hotel except a small bag for the overnight and walked around and across Estacion Wanchaq to a van parked in front of Inka Express Tours on Av. El Sol.

We were the first passengers in the van. As the driver went around Cusco picking up a couple of more people, we got a great look at the city. The van coincidentally started by picking an Australian couple up from around Plazoleta Santo Domingo which we had walked the day before.

We also got another glimpse of the residual Inca structure of Coricancha below the Convent of Santo Domingo:

View from the van of Cusco streets in the morning.

Plazoleta Santo Domingo square as seen from the van.

Colonial buildings and narrow streets in Cusco from the moving van.

Residential area of Cusco with traditional red-tiled roofs.

Those red-tiled roofs are actually a Spanish introduction. The Incas used thatched roofs, which were better insulated but flammable. The Spanish tiles (called "tejas") became standard after colonization. What's interesting is that the tiles are often held in place not with nails or mortar, but with the weight of other tiles - a clever system that allows for expansion and contraction during temperature changes and earthquakes.

View of Cusco's outskirts with mountains in the distance.

Local market street in Cusco as the van passes through.

Leaving Cusco city, view of the surrounding valley.

Traditional wooden balcony overhanging a street in Cusco.

View of a Cusco neighborhood with laundry hanging outside.

Those wooden balconies are called "balcones coloniales" and are another Spanish introduction. They served practical purposes - allowing people to see the street without being seen, and providing shade from the intense Andean sun. The laundry hanging outside isn't just for lack of dryers - in the thin mountain air, clothes dry incredibly fast, especially in the strong sunlight. Plus, electricity is expensive in Peru, so sun-drying makes economic sense.

Eventually a bilingual tour guide boarded our van in front of the SUNAT (Superintendencia Nacional de Aduanas y de Administración Tributaria - Customs and Tax) building before heading out of the city.

SUNAT building in Cusco where the tour guide joined the van.

SUNAT is Peru's tax authority, similar to the IRS in the US. Peru has a surprisingly efficient tax collection system for a developing country, with a VAT (Value Added Tax) of 18% on most goods and services. Tourists can get a refund on VAT for some purchases when leaving the country, but the process is complicated enough that most don't bother.

We then started going up Route 28G north of Cusco city. The panoramic Cusco valley gradually came into view receding as we climbed up towards the Inca complex archeological site of Saqsaywaman sitio arqueologico de Llaullikasa.

Panoramic view of the Cusco valley from Route 28G.

View of terraced hillsides in the Cusco valley.

Those terraces aren't just pretty landscaping - they're ancient agricultural engineering marvels. The Incas built terraces (called "andenes") to create flat growing spaces on steep slopes, prevent erosion, and maximize sun exposure. Different crops were planted at different elevations - potatoes at higher, colder levels; corn at middle elevations; fruits and coca at lower, warmer levels. Some terraces even had built-in irrigation systems and different soil types for different crops.

Scenic overlook of the Sacred Valley from the mountain road.

View of distant mountain ranges from the road to Pisac.

Roadside view of agricultural terraces in the Andes.

Small village along Route 28G in the Cusco region.

We continued across the town of Ccorao, Institucion Educativa Inca Ripaq college, Cochahuasi Amimal Sanctuary and the village of Huancalli.

The town of Ccorao along the route to the Sacred Valley.

Institucion Educativa I.E. Inca Ripaq college building.

Entrance to Cochahuasi Animal Sanctuary.

Scenery near Huancalli village with traditional houses.

Andean landscape with agricultural fields along the route.

View of the Urubamba River valley from the road.

The Urubamba River is the lifeblood of the Sacred Valley. It starts as the Vilcanota River near Lake Titicaca and eventually becomes the Ucayali, then the Amazon. The Incas called it Willkamayu (Sacred River) and considered it a reflection of the Milky Way on earth. The river carved the Sacred Valley over millions of years, and its waters irrigate the fields that have fed civilizations for millennia.

The Sacred Valley of the Incas

Just before reaching the city of Pisac, we stopped at Mirador Taray viewing point for our first look at the legendary Sacred Valley of the Incas - the fertile Urubamba river valley stretching from Pisac to Ollantaytambo. The rich soil has supported many civilizations from ancient times - Chanapata (800 BCE), Qotacalla (500 CE), Killke (900 CE) and Inca. (Ref: Wikipedia)

Panoramic view of the Sacred Valley of the Incas from Mirador Taray.

The Urubamba River winding through the Sacred Valley.

Terraced mountainsides and farmlands in the Sacred Valley.

View of the valley floor with scattered settlements.

The Sacred Valley isn't just a pretty name - it was literally sacred to the Incas. They believed it was the earthly reflection of the celestial river (the Milky Way). The valley runs east-west, which is unusual in the Andes (most run north-south), giving it more sun exposure and making it warmer and more fertile than surrounding areas. At an elevation of around 9,000 feet, it's lower than Cusco, which makes it more comfortable for growing crops (and for tourists to breathe).

Pisac

Women and alpacas in the town of Pisac in the Sacred Valley.

The current Pisac city sits on the banks of Vilcanota river (another name for Urubamba river in these parts) in the Sacred Valley of the Incas. Crossing the bridge over Vilcanota, we stopped a bit in the famous Pisac market on our way back from the ruins for a little while. The deserted streets were devoid of the usual throngs of tourists due to ongoing socio-political crisis in Peru.

Bridge over the Vilcanota River leading into Pisac.

That bridge is modern, but bridges have been crucial in the Andes for millennia. The Incas built suspension bridges from woven grass fibers that could span hundreds of feet. The most famous was the Q'eswachaka bridge, which is still rebuilt annually using traditional techniques. The Spanish introduced arch bridges, but many collapsed in earthquakes. Modern bridges like this one use reinforced concrete, but still follow the basic arch design that works well in earthquake-prone areas.

Street in Pisac with colonial-style buildings.

Empty streets in Pisac market area due to political unrest.

Normally, Pisac's market would be packed with tourists buying souvenirs, but the political crisis kept them away. This was bittersweet - great for us having the place to ourselves, but terrible for local artisans who depend on tourism for their livelihoods. Peru's economy gets about 4% of its GDP from tourism, and in places like Pisac, that percentage is much higher.

Traditional market stalls in Pisac, mostly empty.

Colorful textiles for sale at a Pisac market stall.

Handcrafted jewelry and souvenirs at Pisac market.

Local woman selling fruits at the Pisac market.

Street vendor with traditional hats and bags.

Those traditional hats are called "chullos" and are knitted from alpaca wool. They have ear flaps that can be tied under the chin. The patterns aren't random - they often represent animals, mountains, or other elements important to Andean culture. The pom-poms aren't just decorative; in some communities, they indicate marital status. A red pom-pom might mean single, while other colors indicate married, widowed, etc.

View of Pisac's main square with colonial church.

Colonial-era church in Pisac's central plaza.

That church was built in the 17th century, probably using stones from Inca structures. Like many colonial churches in Peru, it sits on what was likely an important Inca site. The Spanish deliberately built churches on Inca holy places to demonstrate the triumph of Christianity over "pagan" religions. Inside, you'd typically find artwork that blends European and indigenous styles - saints with indigenous features, or Christian symbols mixed with Andean motifs.

Narrow street in Pisac with stone walls.

Local bakery or food shop in Pisac.

View of Pisac valley with terraced hillsides.

Those terraces in the distance are the Pisac ruins, which we were about to visit. From down here in the town, you can appreciate how enormous the complex is. It's not just a few buildings - it's an entire city built into the mountainside. The Incas didn't just adapt to their environment; they transformed it on a massive scale.

Traditional Peruvian textiles displayed in Pisac.

Street musician playing traditional music in Pisac.

Local artisan weaving textiles in Pisac market.

That weaver is practicing a tradition that dates back over 2,000 years in the Andes. Andean textiles are among the most sophisticated in the ancient world. The Incas didn't have written language, so textiles served as a form of communication, recording history, genealogy, and even mathematical information. Different patterns represented different communities, social status, or religious concepts. The weaving technique shown here is probably backstrap weaving, where one end of the loom is tied to a post and the other to the weaver's body.

Traditional Peruvian hats (chullos) for sale.

Colorful hand-woven blankets at a market stall.

Pottery and ceramic goods for sale in Pisac.

Street food vendor in Pisac preparing local dishes.

Local woman selling fruits and vegetables.

View of Pisac's mountainous surroundings.

Traditional adobe houses in Pisac with mountain backdrop.

Those adobe houses are made from mud bricks dried in the sun. Adobe is an excellent building material for the Andes - it's cheap, readily available, and provides good insulation against both heat and cold. The thick walls keep interiors cool during the day and warm at night. Many adobe houses in Peru have survived for centuries, though they do require regular maintenance, especially during the rainy season.

Inca Ruins of Pisac

View of the Pisac Inca ruins from a distance.

Terrace walls of the Pisac Inca complex.

Emperor Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (1418 - 1472), ninth Sapa Inca of the Kingdom of Cusco, was a great conqueror who transformed the Kingdom to an Empire by annexation. Pachacuti conquered the area of Pisaq and constructed a great city complex starting c.1440 CE consisting of residences, citadel, astronomical observatory and religious sites. The wonder that is Machu Picchu was another estate of Pachacuti, as was Ollantaytambo, both of which we would visit next. (Ref: Wikipedia)

Portrait of Inca Emperor Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui.

Inca Emperor Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui

By Cuzco School - cuadro cusqueño, Public Domain, Link

Pachacuti was basically the Alexander the Great of the Andes. His name means "He who shakes the earth" or "Earthshaker," which gives you an idea of his impact. Before Pachacuti, the Incas were just one of many small kingdoms in the Cusco Valley. After Pachacuti, they controlled an empire stretching from modern-day Colombia to Chile. He didn't just conquer; he revolutionized Inca society, creating the administrative systems, road networks, and architectural styles that defined the empire.

Panoramic view of the Pisac Inca ruins showing multiple terraces.

Wide panorama of the Pisac Inca terraces and structures.

Pisac was a retreat for the royal family and entourage away from Cusco, a place to rest between wars, celebrate victories, perform rituals and religious ceremonies and take refuge in its safety when needed.

Francisco Pizarro and Spanish invaders destroyed the Pisac Inca complex (and numerous others) starting the 1530s. Such a remarkable city was not even chronicled by the Spaniards!

Close-up of Inca stone masonry at Pisac ruins.

That stonework is the signature of Inca architecture. The technique is called "ashlar masonry" - stones are cut to fit together perfectly without mortar. What's incredible is that they did this with stone tools (bronze was available but too soft for cutting hard stones). They likely used harder stones to shape softer ones, sand for polishing, and a lot of patience. The irregular shapes actually make the walls more earthquake-resistant than straight, regular stones would be.

View of agricultural terraces at Pisac ruins.

Pathway through the Pisac ruins with stone walls.

Ruins of residential structures at Pisac.

View of the valley from the Pisac ruins.

Stone steps leading through the Pisac complex.

Inca stonework showing precise fitting without mortar.

View of multiple terrace levels at Pisac.

Remains of Inca buildings on the mountainside.

Pathway through the ruins with valley view.

View of the ceremonial area at Pisac ruins.

Stone structures integrated into the mountain terrain.

View of Pisac's terraced hillside from below.

Detailed view of Inca stone masonry technique.

Remains of Inca walls with trapezoidal niches.

Those trapezoidal niches and doorways are another signature of Inca architecture. They're not just aesthetically pleasing - they're earthquake-resistant. The wider base and narrower top make the structure more stable. The trapezoidal shape also has astronomical significance - it frames certain celestial events at specific times of year. Many Inca doorways align with solstices or equinoxes.

View of the valley from a high point in the ruins.

Remains of ceremonial structures at Pisac.

The current town of Písaq in the Sacred Valley below the ruins of the Inca complex was built by Viceroy Toledo in the 1570s. However, it would not be till 1877 that the Inca city of Pisac would be documented. Ephraim George Squier, United States Commissioner to Peru first described Pisac in his book "Peru - Incidents of Travel and Exploration in the Land of the Incas". At the same time, Austrian-French scientist-explorer Charles Wiener also visited Písac and chronicled his explorations in 1880 in his book "Perou et Bolivie". (Ref: Wikipedia)

View of the Pisac valley from the ruins.

That view explains why the Incas chose this location. From up here, you can see the entire valley - perfect for spotting approaching enemies. The terraces provided food security. The high elevation offered natural defense. And the spiritual connection to the mountains and sun would have been powerful here. For the Incas, mountains weren't just geological features; they were deities called "apus." The highest peaks were the most powerful apus.

Inca Burial Caves with Mummies

Cliff face with Inca burial caves at Pisac.

Large burial sites in the form of numerous caves are seen on mountains behind agricultural terraces of Inca complexes including Pisac. It is estimated about 5,000 of those caves in Pisac have been plundered by Spaniards for the goodies, but at least 5,000 more remained undiscovered, possibly more even today. (Ref)

Close-up view of burial caves in the mountainside.

Multiple burial caves visible in the cliff face.

The Inca concept of death is unusually fascinating. Instead of saying their goodbyes and creating some sort of memorials to remember the dead by and move on, the Inca dead continued to participate in the affairs of the living.

Andean civilizations have been mummifying their dead from about 2,000 years before the Egyptians. The Incas mummified their dead in layers of cloth and put them in fetal positions inside cave burial chambers. Food, tools, utensils and other useful items were wrapped and placed with them to make their return to this world easier. Gold and jewelry were also placed with the mummies of upper classes and royalty, resulting in Spaniards often throwing the mummies out of the caves and grabbing the valuable.

The cave burial chambers remained accessible to the Incas to place more mummies. They would also take mummies out for participation in celebrations and special events. Mummified ancestors would be paraded behind living emperors, for example, their history and achievements adding to those of the living. Even today on Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) Peruvians gather around their ancestors' burial sites, sing and play music and have a meal with them before leaving them with food. (Ref: Smithsonian Magazine and Inkaterra)

Those burial caves are called "chullpas" and they're found throughout the Andes. The Incas believed in three worlds: Hanan Pacha (the upper world of gods and future), Kay Pacha (our world), and Uku Pacha (the inner world of the dead and past). By placing mummies in caves (openings to Uku Pacha), they maintained connection with ancestors who could influence the living world. The fetal position represents rebirth - the deceased was ready to be born into the next life.

Ollantaytambo Inca Ruins

View of the Ollantaytambo Inca ruins with terraces.

From Pisac, we drove north on Peru Route 28B crossing the city of Urubamba to Ollantaytambo Inca ruins on the other end of the Sacred Valley of the Incas.

The Sacred Valley at Ollantaytambo with mountains in background.

Another spectacular Inca complex with terraces leading up to a fortress and a temple, Ollantaytambo too was built by the 9th Sapa Inca - Emperor Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui. The especially strong walls of the complex were built of stone moved and lifted up from the opposite side of Urubamba river, a feat that required diverting the river itself! In addition, Llamas and Alpacas are not load-bearing animals, and all stone movement was accomplished with human labor.

Coffee shop at Ollantaytambo Inca Ruins: the logo looks familiar?

Later on, this is where Spanish invasion-era Inca emperor Manco Inca Yupanqui (1515 - 1544) famously defeated the invaders using a brilliant move of flooding the valley below via carefully engineered channels.

Though the Spaniards would return with greater force later and continue their destruction, the remains today are still a testament to the achievement of the Incas. (Ref: Lonelyplanet, Wikipedia)

Terrace walls of Ollantaytambo leading up to the temple.

View of the Ollantaytambo fortress from below.

Pathway through the Ollantaytambo ruins.

Stone structures at Ollantaytambo with mountain backdrop.

View of the agricultural terraces at Ollantaytambo.

Ollantaytambo is special because it's one of the few places where the Spanish actually lost a major battle during the conquest. In 1536, Manco Inca used the complex's sophisticated water channels to flood the plain below, trapping Spanish cavalry in mud. He also rolled boulders down on them from above. The Spanish retreated, though they would return with reinforcements. Today, Ollantaytambo is also the starting point for the Inca Trail trek to Machu Picchu.

Ollantaytambo Wall of the Six Monoliths: Temple of the Sun (Templo del Sol)

The Templo del Sol, also known as Wall of the Six Monoliths, at Ollantaytambo ruins is of special historical interest. It is hypothesized this wall was actually built by the much earlier Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) civilization whose central city was at over 13,000 feet at the Tiwanaku complex on southern basin of lake Titicaca far away in Bolivia, dated to c.110 BCE. We visited Bolivia including Tiwanaku a few days later, described in this post.

The Wall of the Six Monoliths is mind-boggling. Each pink granite stone weighs between 50-80 tons, and they were quarried from a mountain across the valley, 6 kilometers away. How did they move them? Probably with log rollers, ropes, and hundreds of workers. But here's the crazy part: they had to cross the Urubamba River. They may have built a temporary dam to divert the river, moved the stones across the dry riverbed, then removed the dam. That's infrastructure planning that would impress modern engineers.

Urubamba and Hotel San Agustín Monasterio de la Recoleta Boutique: Night Halt

Having completed a long day of marvelling at Inca complexes, we drove south on Rt. 28B back to Urubamba and checked into the remarkable San Agustín Monasterio de la Recoleta boutique hotel.

View of Urubamba town in the Sacred Valley.

Urubamba has a big mysterious "711 DIMA" sign etched on a hill. It turns out there is a school number 711 called DIMA. As a right of passage, students of that school climb up the hill and sculpt the number and name on the hillside. This is not easy and even dangerous. (Ref: Flickr)

"711 DIMA" sign carved into a hillside near Urubamba.

Traditional wooden balcony in Urubamba.

Street scene in Urubamba with local shops.

Railroad crossing in Urubamba.

Once again, we were the only guests checking in at the San Agustín Monasterio de la Recoleta monastery, and the only family dining at their luxurious restaurant. We had the entire monastery to ourselves! After dinner we hit luxurious beds in large comfortable suites of the monastery, tired and easily drifting off to sleep dreaming about the train to Machu Picchu and the wonder of the world planned for the next day.

Exterior of San Agustín Monasterio de la Recoleta hotel.

Courtyard of the monastery hotel.

Hotel room interior at the monastery.

Hotel hallway with colonial architecture.

Dining area of the hotel restaurant.

Hotel courtyard with fountain.

Architectural detail of the monastery building.

View of the hotel gardens.

This monastery-turned-hotel is typical of Spanish colonial architecture in Peru. The thick walls, central courtyard, and arched walkways are designed for the climate - keeping interiors cool during the day and warm at night. The fountain in the courtyard isn't just decorative; it provides fresh water and cools the air through evaporation. Many such monasteries were built in the 17th and 18th centuries as the Spanish consolidated their control over Peru.

December 24, 2022

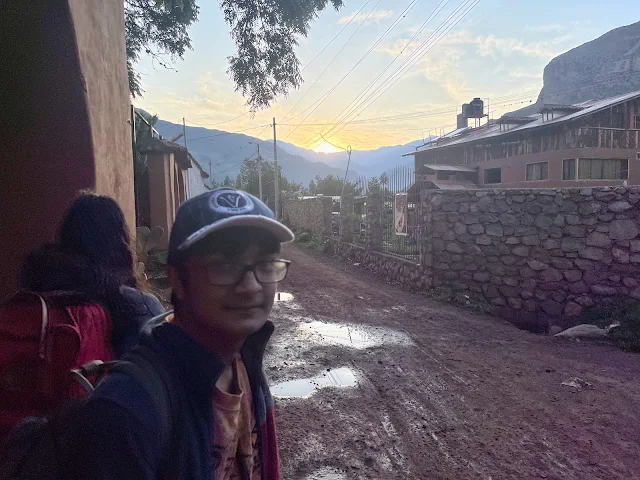

4:30 AM, rise and shine! Recuperated and rested, we check out of San Agustín Monasterio de la Recoleta monastery hotel, Urubamba and get back on the road: North Route 28B to Ollantaytambo Train Station.

Early morning view of the monastery hotel at checkout.

Sunrise over Ollantaytambo.

Incarail 360° Machu Picchu Train: The best scenic train in Peru

Illustration from Tintin's "Prisoners of the Sun" showing a train in Peru.

We reached the Incarail terminal at Ollantaytambo at 6:30 AM with ample time in hand for the 7:22 AM 360° Machu Picchu Train. We were early enough to watch the train before ours depart.

Incarail and Perurail train station at Ollantaytambo.

Train platforms at Ollantaytambo station.

There is a free and convenient Left-luggage service to the left of the ticket office across the street from the passenger waiting rooms. We deposited our overnight luggage there.

Left luggage service office at Ollantaytambo station.

Sign for left luggage service at the train station.

We grabbed some excellent coffee and pastries from Mayu Coffee Bar Station next to waiting rooms and settled down to wait to be called to board the train.

Mayu Coffee Bar at Ollantaytambo train station.

Interior of Mayu Coffee Bar.

Ollantaytambo isn't just a train stop; it's a living Inca town. While you sip your coffee at Mayu, you're sitting in a valley that was the royal estate of Emperor Pachacuti in the 15th century. The town's layout is original Inca urban planning – those narrow cobblestone streets and irrigation channels have been functioning for over 500 years. The name "Ollantaytambo" comes from a legendary Inca romance story about a general named Ollantay who fell in love with the emperor's daughter. Spoiler: it didn't end well for him at first. The station itself is the gateway to the Sacred Valley, where the Urubamba River carves through mountains that were once the spiritual and agricultural heartland of the Inca Empire. The coffee beans in your cup? Probably grown on the eastern slopes of the Andes, where the Amazon basin begins.

Passenger waiting room at Ollantaytambo station.

Another view of the station waiting area.

Passengers waiting in the station lounge.

The anticipation in these waiting rooms is a modern echo of ancient journeys. For the Incas, this valley was part of the Qhapaq Ñan, the immense road system that stretched from Colombia to Argentina. Ollantaytambo was a major administrative and religious center. The stones used to build the fortress here were dragged from a quarry 4 miles away, across the river and up the mountain – a feat that makes waiting for a 21st-century train seem pretty trivial. The geology here is dramatic: you're surrounded by sedimentary rocks that were pushed skyward when the Nazca Plate dove under the South American Plate, creating the Andes. The waiting area's large windows frame views of the Pinkuylluna mountain, which has ancient granaries (collcas) built into its face by the Incas to store food using natural ventilation. Those granaries are still there, watching over the station like stone sentinels.

When it was time, a group of happy Peruvians clad in bright traditional dresses arrived at the waiting room to usher passengers to the train with much singing, dancing and beating of drums along the short walk to the platform. We did not know this was part of the package and were pleasantly surprised!

There were only a handful of passengers due to political turmoil and violent social unrest in Peru. We shared our entire carriage with just one other family visiting from Australia (not the same Austrailian tourists we met on the van before).

Incarail 360° Machu Picchu Train at Ollantaytambo station.

Incarail train ticket for the journey to Machu Picchu.

That train ticket is your passport to one of the great railway journeys. The line itself is an engineering marvel, built in the early 20th century to connect Cusco to the newly "discovered" Machu Picchu. It climbs along the Urubamba River, which the Incas considered a sacred manifestation of the Milky Way on Earth (Mayu). The river's relentless flow has carved a deep canyon through granite and limestone over millions of years. As you board, you're following in the literal tracks of everyone from Hiram Bingham's expedition to generations of pilgrims, both ancient and modern. The train cars, with their panoramic windows, are designed to make you feel like you're flying through the valley – a nice touch, considering the Andean condor, a sacred bird, soars on these thermals.

At last we were on the famous Inca Rail 360° Machu Picchu Train that easily makes it to any list of most scenic railroads of the world! (Also see White Pass & Yukon Route Railway)

View from the train window showing the Urubamba River.

Scenic view of mountains along the train route.

Train winding along the river valley.

As the train snakes along the Urubamba, you're traveling through a geographic and spiritual transition zone. The mountains here are part of the Vilcabamba Range, a final stronghold of the Inca resistance after the Spanish conquest. The vegetation changes before your eyes: you start in the dry, high-altitude valley near Ollantaytambo and gradually descend into a lush, cloud-forest canyon. This is because you're moving from the Andean highlands (suni and puna ecological zones) down toward the Amazon basin (yunga). The Incas valued this route not just for its beauty, but for its access to diverse crops and resources. Every twist in the track reveals a new microclimate. Look for bromeliads and orchids clinging to the cliffs, and if you're lucky, you might spot a torrent duck riding the river's rapids.

|

| View of agricultural fields from the train. |

Train passing through a tunnel along the route.

Those agricultural fields you see are modern versions of an ancient practice. The Incas were master agriculturalists, and they built terraces (andenes) all over these slopes to grow potatoes, quinoa, corn, and hundreds of varieties of other crops. The tunnels the train goes through are reminders of the sheer difficulty of building this railway—blasting through solid rock to follow the river's path. Local folklore says that certain tunnels and bends in the river are guarded by apu spirits, mountain deities who demand respect. Travelers in Inca times would make offerings of coca leaves or chicha (corn beer) to ensure a safe passage. Maybe that's why the train staff serves you a drink—it's the modern, tasty version of a ritual offering!

View of the river and mountains from the train.

Scenic view of the cloud forest along the route.

The cloud forest is a magical place, where mist hangs like cobwebs in the trees. This humid ecosystem is a biodiversity hotspot, home to spectacled bears, cock-of-the-rock birds, and countless insects. For the Incas, this environment was rich in symbolic meaning. The clouds were seen as the breath of the earth, and the forest was a liminal space between the world of humans and the world of spirits. The river's roar is constant, a sound the Quechua people call huaycco. You're now deep in the canyon, and the air feels thicker, warmer. You've left the open valleys behind and entered the green, dripping embrace of the mountains on the final approach to Machu Picchu.

Midway through the train journey, an actor and actress in traditional Peruvian attire presented a little play, acting out a Peruvian love story of how a girl who first rejected a lover changes her mind when the lover does some special things.

Actors performing a traditional love story play on the train.

Close-up of actors in traditional costume during the performance.

Audience watching the play performance on the train.

This onboard theater is more than just entertainment; it's a living thread of Andean culture. The story they're performing likely has roots in oral traditions passed down for generations. Andean folklore is full of tales of love, trickery, and the intervention of nature spirits. The costumes are authentic: women often wear layered skirts (polleras), embroidered blouses (blusas), and distinctive hats that can indicate their specific village or region. The men's chullos (knit hats with ear flaps) and ponchos are not just for show—they're practical for the cold Andean nights. The play itself might be a gentle lesson in community values, where persistence and cleverness win the day, a theme as old as the mountains outside your window.

The one-and-a-quarter hour train journey ended with the train pulling into Machu Picchu station in Machu Picchu pueblo (town).

Incarail train arriving at Machu Picchu station.

Passengers disembarking from the train at Machu Picchu.

Machu Picchu train station building.

Aguas Calientes: Machupicchu Town / Pueblo / Village

Machupicchu town (sometimes called Machupicchu village) used to be called Aguas Calientes due to the hot springs around. It did not exist before 1920 when it started off as a hub for rail construction workers. It morphed into a tourist town on completion of the railroad in 1931. The only main street Av. Pachacutec runs between the natural hot spring baths and the main square next to the train station.

Main street of Aguas Calientes (Machu Picchu Pueblo).

Devoid of history and with the unmistakable vibe of a tourist town that sees 7,000 visitors pass through every normal day, Machupicchu town is still pretty enough for strolling around. Again, streets that overflow with tourists were empty due to Peru's political crisis.

From the station, a bridge across the Vilcanota river (Urubamba river) takes us into the main square and bus stand.

Bridge over the Vilcanota River in Aguas Calientes.

View of the river from the bridge in Aguas Calientes.

That river you're crossing isn't just water; it's the lifeblood of the Sacred Valley. The Urubamba/Vilcanota is considered a sacred apu (mountain spirit) in female form. Its waters originate from glaciers near the Ausangate mountain, one of the most sacred peaks in Inca cosmology. The bridge is your transition point from the utilitarian train town to the gateway of the ancient sanctuary. The roar you hear is the sound of the river cutting through the granite of the canyon, a process that's been ongoing for over 60 million years since the Andes first rose. The mist often hanging over the water adds to the mystical atmosphere—the Incas believed such places were portals (pacarina) to other worlds.

Main square of Aguas Calientes with tourist information.

Shops and restaurants along the main street.

Tourist shops selling souvenirs in Aguas Calientes.

Restaurants and cafes in Aguas Calientes.

The souvenirs in these shops tell a cultural story. You'll see replicas of Inca stonework, textiles with traditional patterns (tokapu), and figures of Pachamama (Earth Mother). The food in the restaurants is a fusion of Andean staples and tourist tastes. Try cuy (guinea pig) if you're adventurous, or stick with lomo saltado, a stir-fry that reflects Peru's Chinese immigrant influence. The town exists solely because of the ruins above, a classic example of "tourism geography." It's built on a precarious floodplain, and major floods in 2004 and 2010 reminded everyone of the river's power. The hot springs that gave the town its original name are geothermal features, heated by the same tectonic forces that built the Andes.

It is here we get on a bus to Machu Picchu. There is also a 6 KM / 3.7 mile trail that some people take instead of the bus.

Bus stop in Aguas Calientes for buses to Machu Picchu.

Machu Picchu (Quechua: "Old Mountain")

Panoramic view of Machu Picchu from the House of the Guardian.

Another panoramic view of Machu Picchu ruins.

That first glimpse is literally breathtaking, partly because of the altitude (2,430 meters / 7,970 ft), but mostly because of the sheer audacity of it. Machu Picchu sits on a saddle between two peaks: Machu Picchu (Old Peak) and Huayna Picchu (Young Peak). It's perched on a granite ridge, a rock type called "Vilcapampa granodiorite," which the Inca stonemasons expertly split and shaped. The site was likely built around 1450 CE as a royal estate for Emperor Pachacuti. It was abandoned about 100 years later during the Spanish Conquest, but because it was never found by the Spaniards, it remained remarkably preserved. The jungle crept in and hid it for centuries, which is why it's often called the "Lost City," though local Quechua people always knew it was there.

Our bus goes up the zigzagging Hiram Bingham road to the entrance of the ruins. The road (and the Perurail train) are named after American archaeologist and United States senator Hiram Bingham who exposed Machu Picchu to the world with his superhit book "Lost City of the Incas" after his travels in early 20th century. However, Bingham was unlikely to be the first westerner to have reached Machu Picchu. (Ref: Britannica)

Hiram Bingham Road winding up to Machu Picchu.

House of the Guardian to the Funerary Rock at Machu Picchu

We hike up to the Casa del Guardián de la Roca Funeraria to meet llamas and take a couple of foto tipica of the man-made wonder of the world! As luck would have it, we were there on a clear sunny day with just a couple of hundred visitors across the sprawling complex for the entire day.

View of Machu Picchu from the House of the Guardian viewpoint.

Classic view of Machu Picchu with Huayna Picchu in background.

The House of the Guardian is the perfect spot for that iconic photo because the Incas designed it that way. This hut likely housed the caretakers of the site. The view isn't accidental; it frames the entire city with Huayna Picchu as a dramatic backdrop, demonstrating the Inca principle of integrating architecture with the natural landscape. The llamas wandering around aren't just cute photo-bombers; they're descendants of animals crucial to Inca life, providing wool, meat, and serving as pack animals. They also act as natural lawnmowers, keeping the grass trim. Huayna Picchu isn't just a pretty peak; it was a site of important temples and residences, possibly for the elite. The climb is notoriously steep, involving stone steps and cables—not for the faint-hearted.

Machu Picchu with clear skies and few visitors.

View of the agricultural terraces at Machu Picchu.

Those agricultural terraces are a masterpiece of engineering. They're not just steps for farming; they're a complex drainage system. Each layer has a base of crushed stone for drainage, followed by gravel, sand, and topsoil. This prevented waterlogging and erosion, allowing the Incas to grow crops on incredibly steep slopes. They grew corn, potatoes, quinoa, and even coca (for ritual and medicinal use). The terraces also stabilized the mountain side, preventing landslides. This is "landscape architecture" on a grand scale, turning a precarious cliff into a productive garden. It's a testament to how the Incas didn't just occupy land; they sculpted and improved it.

Panoramic view of Machu Picchu complex.

Llamas grazing at Machu Picchu near the viewpoint.

The llamas are more than scenery; they're a living link. In Inca mythology, llamas were created by the god Viracocha from clay and brought to life. A black llama was sometimes sacrificed in ceremonies to ensure rain and good harvests. Their presence on the terraces today is wonderfully symbolic—they're grazing on lands that once fed the empire. Their wool was used for clothing and their dung for fuel. They're also incredibly sure-footed, perfectly adapted to the steep terrain. They seem to pose regally, knowing they're the true heirs to this place.

Visitor photographing Machu Picchu from the viewpoint.

Llamas at the House of the Guardian viewpoint.

Close-up of a llama at Machu Picchu.

Getting up close with a llama is a classic Machu Picchu experience. They're camelids, related to alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos. The Incas domesticated llamas over 4,000 years ago. They can't carry huge weights (about 40-60 lbs), but they were the trucks of the empire, moving goods along the steep trails. Their wool comes in various natural colors, which the Incas used to create intricate textiles without dye. They're also surprisingly vocal, making a humming or clucking sound. Just don't try to hug one; they might spit if they feel annoyed—a defense mechanism involving regurgitated stomach contents. Not the souvenir you want.

View of the ruins with mountainous backdrop.

Mountains of Machu Picchu complex.

The mountains aren't just a backdrop; they're central to the site's purpose. The Incas revered mountains as apus, powerful spirits that protected people and provided water. Machu Picchu is aligned with key astronomical events and sacred peaks. On the winter solstice, the sun rises directly through a notch in the mountains as seen from the Intihuatana stone. The surrounding peaks—Machu Picchu, Huayna Picchu, Putucusi, and the distant Salcantay—were all considered deities. The site's location, hidden high in the clouds, was likely chosen for its spiritual potency and defensive position. It feels remote today; imagine how mystical it felt 500 years ago.

Stone structures of Machu Picchu against green mountains.

View of Machu Picchu's terraces and structures.

The stonework is what truly boggles the mind. The Incas were master stonemasons without using iron tools, the wheel, or mortar. They used harder stones and sand to grind and shape granite blocks so precisely that a knife blade can't fit between them. This technique, called ashlar masonry, made buildings incredibly earthquake-resistant. The stones could move slightly during tremors and then settle back into place. The different styles of masonry indicate social hierarchy: finely cut stones for temples and royalty, rougher stones for commoners' homes. It's like reading a social map in rock.

Llama at Machu Picchu complex.

View of the main ruins area from a higher vantage point.

From above, you can appreciate the urban planning. The city is divided into agricultural, residential, and religious sectors. The layout reflects Inca cosmology and social order. The peak of Huayna Picchu acts as a giant sundial at certain times of year. The Incas used a sophisticated system of canals and fountains to bring fresh water from a spring on the mountain. They also had an intricate drainage system to handle the heavy rains. This wasn't just a random collection of buildings; it was a carefully engineered masterpiece designed to function in harmony with the extreme environment.

Detail of Inca stonework at Machu Picchu.

Llamas among the ruins.

View of Machu Picchu with surrounding mountains.

Another view of the iconic Machu Picchu scene.

Machu Picchu Complex Map and Tour Route

Map of Machu Picchu showing Circuit 2 tour route (source).

Old City Gates to Machu Picchu

We then headed down to Puerta de la Ciudad - the old city gates to Machu Picchu.

The old city gates (Puerta de la Ciudad) at Machu Picchu.

View through the city gates into Machu Picchu.

Passing through the gates, you're entering the urban sector. This was a controlled entry point, emphasizing that Machu Picchu was a special, possibly restricted, place. The gates would have had wooden doors that could be secured. Inside, you move from the agricultural outskirts into the heart of the administrative and residential areas. The change in stonework marks the transition: inside the gates, the masonry is finer, indicating more important buildings. You're walking the same path that Inca nobles, priests, and royalty would have used.

Stone doorway at the city entrance.

Pathway leading from the city gates.

View of residential structures near the gates.

There are ruins of residences - big houses to the left of and below the El Templo del Sol (Temple of the Sun). Streets with spacious multi-storied houses on both sides are easily identified.

Residential houses below the Temple of the Sun at Machu Picchu.

These residences were likely for the elite—nobles, administrators, or important artisans living close to the Temple of the Sun, the most sacred structure after the Intihuatana. The size and quality of construction indicate high status. Inca society was highly stratified, and your proximity to sacred spaces reflected your social rank. The houses often have trapezoidal doors and niches, a signature Inca architectural style that's stronger than rectangular shapes. The niches likely held idols or precious objects. Life here would have been privileged but also regimented, governed by religious ceremonies and the demands of the imperial estate.

We headed to the Quarry Group from where building material for the city of Machu Picchu was extracted. There is still unfinished stone lying around. Transporting stone was a human endeavor for the Incas who neither used wheeled vehicles nor load-carrying animals. Llamas are incapable of carrying more than about 40 pounds anyway.

The Quarry Group at Machu Picchu where stones were extracted.

Unfinished stones left at the quarry site.

The quarry is a fascinating workshop frozen in time. You can see the techniques: workers would hammer wooden wedges into natural fractures, then pour water on them. The wood would expand, splitting the rock. Then, they'd shape the stones using harder river rocks as hammers. The unfinished stones show that work stopped abruptly, perhaps when the site was abandoned. Moving these multi-ton blocks without wheels or beasts of burden is mind-blowing. They likely used log rollers, levers, and earthen ramps, with hundreds of men pulling with ropes. It was a massive communal effort, a testament to the power of the Inca state to mobilize labor. Some myths suggest the stones were softened by a magical plant juice—a fun story, but the reality of sweat and engineering is even more impressive.

View of the quarry area with cut stones.

Stone extraction marks in the quarry.

Oh - hi there! We met our first Chinchilla - the native rodent of the Andes - on our way to the Agricultural sector.

Chinchilla spotted at Machu Picchu.

That chinchilla is a living piece of Andean ecology! These fluffy rodents are native to the Andes and were highly valued by the Incas for their ultra-soft fur. So valued, in fact, that only royalty was allowed to wear chinchilla pelts. They almost went extinct due to overhunting for the fur trade. Seeing one in the wild at Machu Picchu is a lucky sign—it means conservation efforts are working. They're crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), so spotting one during the day is extra special. In local folklore, they're sometimes seen as good luck charms or messengers from the mountain spirits (apus).

Agricultural Sector and Terraces

The iconic farming terraces of Inca complexes had to be cut into the solid rock of the mountains. The Incas cultivated over 100 kinds of food and medicinal plants, including corn, squash, tomatoes, peanuts, and cotton. Inca farmers were the first to grow potatoes. (Ref: Britannica)

Agricultural terraces at Machu Picchu.

View of multiple terrace levels for agriculture.

Walking among these terraces, you're in the Inca's grocery store and pharmacy. They practiced advanced agronomy, using different terrace levels to create microclimates. Lower, warmer terraces grew corn and coca. Higher, cooler ones grew potatoes and quinoa. They also used companion planting and natural fertilizers like guano from coastal islands. The terraces are a form of landscape sculpture that prevented erosion, conserved water, and maximized arable land in a vertical environment. It's a sustainable farming system that modern permaculturists still study. The Incas didn't fight the mountain; they worked with it, turning a steep slope into a productive, beautiful, and stable foundation for their city.

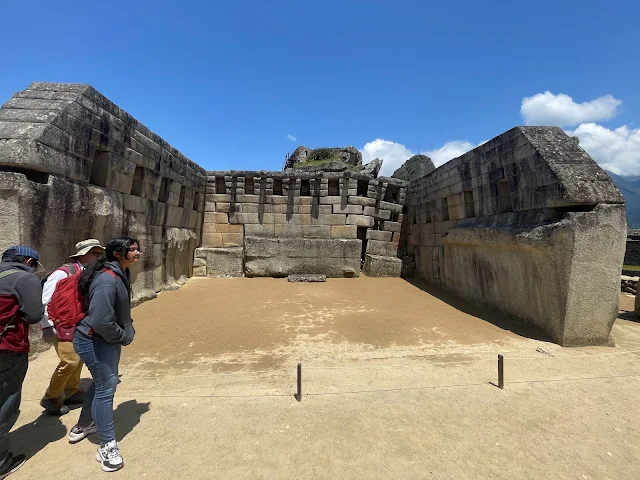

Sacred Plaza and Temple of the Three Windows

With great views of snow-capped mountains and the Vilcanota (Urubamba) river below, Plaza Sagrada has the main temple in the north (featuring another happily sunbathing Chinchilla) and various temples around. The house of high priest is to the south of the plaza. The famous Templo de las Tres Ventanas (Temple of the Three Windows) marks the East. Inti Raymi (Festival of the Sun) and various rituals were held here. The sun dial and degree of precision construction with polished stone continues to amaze!

The Sacred Plaza (Plaza Sagrada) at Machu Picchu.

Stone structures around the Sacred Plaza.