Alpine Peaks & Fairy Tale Towns: A Guide to Switzerland, France & Germany

Switzerland, France and Germany: A Trifecta of European Shenanigans

|

|

German side of the Three Countries Bridge Flags of Switzerland, France, Germany, the European Union and Weil am Rhein This bridge is so international it needs a passport just to cross itself |

This long and juicy roadtrip travel guide takes you overland through the stunning heart of Europe:

- Cities: Paris (France) → Zürich (Switzerland) → Basel (Switzerland) → Huningue (France) → Three Countries Bridge (France, Germany, Switzerland) → Strasbourg (France) → Kehl (Germany) → Baden-Baden (Germany) → Heidelberg (Germany) → Triberg (Germany) → Meiringen (Switzerland) → Lucerne (Switzerland) → Venice (Italy)

- Provinces (Regions): Île-de-France (France) → Grand Est [Alsace] (France) → Canton of Zürich (Switzerland) → Canton of Aargau (Switzerland) → Canton of Basel-Stadt (Switzerland) → Baden-Württemberg (Germany) → Canton of Bern (Switzerland) → Canton of Obwalden (Switzerland) → Canton of Lucerne (Switzerland) → Canton of Glarus (Switzerland) → Veneto (Italy)

Europe has this funny habit of cramming multiple countries into spaces smaller than some American parking lots. Switzerland, France and Germany decided to play a particularly intense game of border hopscotch in this corner of the continent. We'd just finished ogling Parisian opulence and decided to trade baguettes for bratwurst via Switzerland, because why take the direct route when you can involve three currencies, four languages and enough bureaucracy to make a paperwork enthusiast weep with joy?

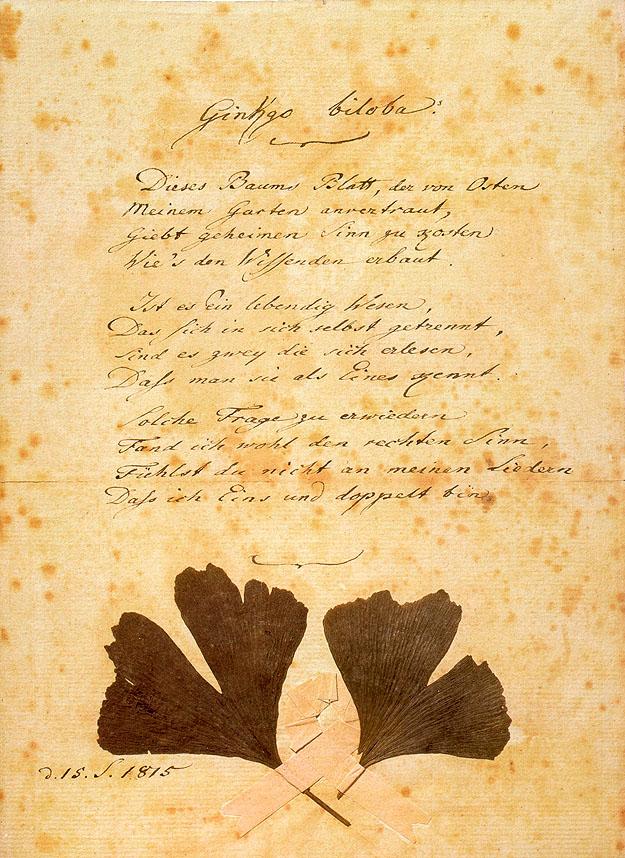

Our route was essentially a literary pub crawl with better scenery. We followed Victor Hugo's hunchback inspiration in Strasbourg, chased Dostoevsky's gambling demons in Baden-Baden, hunted Goethe's ginkgo poem in Heidelberg and nearly tumbled down the Reichenbach Falls like Sherlock Holmes' inconvenient demise. All this while dodging cuckoo clocks in the Black Forest that probably contained more intricate machinery than our first car.

Watch a video slideshow of this segment of our Europe trip

Watch: Switzerland, France and Germany - A European Trifecta

Our video has fewer plot holes than most European political agreements

Here's the complete map of our entire European meanderings, including this segment. It looks like a toddler's crayon drawing after too much sugar, but it gets the job done.

Paris to Zürich on TGV Lyria: France's Land-Based Cruise Missile

|

|

TGV Lyria #4407 at Gare de Lyon, Paris This train travels so fast it arrives five minutes before it leaves French engineering: making speeding look elegant since 1981 |

The TGV Lyria is France's polite way of saying "we could have made this journey take six hours, but we're feeling merciful today." Covering 686 kilometers in just over four hours, these trains hit speeds that would get you arrested in most countries. The "TurboTrain à Grande Vitesse" sounds like something a French superhero would ride, which isn't far from the truth.

Here's a fun nugget: the TGV holds the world record for the fastest wheeled train at 574.8 km/h (357.2 mph), set in 2007. Our train to Zürich was taking it easy at a mere 300 km/h, probably because the conductor wanted to enjoy the view. The original TGV prototype was painted in psychedelic orange and brown livery that looked like it escaped from a 1970s kitchen appliance catalog.

|

|

TGV Lyria #4407 at Zürich HB Arrived with Swiss precision, naturally The train looks relieved to be in a country that appreciates schedules |

The journey treats you to France's Champagne region, where the grapes probably grow faster just to keep up with the passing trains. Then Switzerland appears with Alps so picture-perfect they look Photoshopped. Lake Geneva sparkles like a giant spilled diamond necklace, which is appropriate given Swiss banking sensibilities.

|

|

Champagne, France Where every bubble has a pedigree The only region where soil analysis involves tasting notes |

We discovered a delightful piece of travel trivia about the Champagne region while gazing at those perfect rows of vines. Apparently, in the late 19th century, French vintners were so concerned about phylloxera (tiny root-eating insects) that they imported American grapevines to graft onto. The irony? The solution came from the same continent whose wine they'd been politely ignoring for centuries. Some French winemakers still refer to this as "the great humiliation" over their evening aperitifs.

|

|

Aboard the TGV Lyria Window seat required for Alps viewing The WiFi was faster than our comprehension of Swiss German |

While marveling at the TGV's engineering, we remembered a quirky fact from an old French railway journal. The original 1981 TGV trains had ashtrays in every seat, because apparently hurtling through the countryside at 300 km/h wasn't exciting enough without a cigarette. The ashtrays were quietly removed in the late 1990s, around the same time passengers realized that smoking on a sealed train moving at airplane speeds might not be the brightest idea.

|

|

TGV Lyria approaching platform at Zürich HB The train slows down for Swiss precision docking Even French trains become punctual in Switzerland |

Zürich Hauptbahnhof is so clean you could perform surgery on the platforms. The station handles over 3,000 trains daily and has its own shopping mall because apparently waiting for trains isn't expensive enough. The station's clock tower has the largest clock face in Europe at 8.7 meters diameter, which is Switzerland's subtle way of saying "yes, we know what time it is and so should you."

We picked up our rental car in Zürich, a sensible German sedan that probably had its oil changed at exactly 10,000 kilometers, not 9,999 or 10,001. Our road trip began with a drive through canton Aargau, which sounds like a digestive issue but is actually lovely Swiss countryside.

|

|

Welcome sign for Canton of Aargau, Switzerland Population: people who probably have their taxes filed by January 2nd The canton coat of arms features a shield, because medieval branding |

The Baregg Tunnel: Switzerland's Subterranean Traffic Ballet

Swiss tunnels aren't just holes in mountains - they're meticulously engineered celebrations of not being stuck in traffic. The Baregg Tunnel near Baden is part of the A1 motorway, which is basically Switzerland's main artery. The tunnel has three bores because apparently one or two just wouldn't be Swiss enough.

|

|

Baregg Tunnel 1,390 meters of Swiss efficiency The lighting is probably calibrated for optimal driver happiness |

Digging through some old Swiss engineering archives (metaphorically speaking), we learned that during the Baregg Tunnel's construction, workers discovered a previously unknown geological fault line. Rather than panicking like normal people, Swiss engineers simply redesigned the tunnel's support system on the spot. They probably did the calculations on a napkin during their coffee break, then went back to enjoying their perfectly timed sandwiches.

|

|

Three lanes of westbound bore of Baregg Tunnel Traffic flows smoother than Swiss chocolate Emergency exits every 250 meters, because preparedness |

The first two bores opened in 1970 and are 1,390 meters long. The third bore opened in 2003 and is mysteriously 242 meters shorter, probably because Swiss engineers realized they could save concrete without compromising quality. The tunnel handles over 100,000 vehicles daily, which means statistically, at least three of them are probably running late for very important watch-making appointments.

The safety system includes cameras, sensors and emergency exits monitored 24/7 by experts who probably also have degrees in Swiss watch repair. In an emergency, the system automatically closes the tunnel and alerts authorities, which is more proactive than most relationships.

The Bözberg Tunnel: Jura Mountain Piercing

If the Baregg Tunnel is Switzerland's traffic ballet, the Bözberg Tunnel is its opera. This 3,651-meter twin-tube monster carries the A3 motorway and E60 European route through the Jura Mountains. The tunnel opened in 1996 after construction that was probably timed with atomic clock precision.

|

|

Bözberg Motorway Tunnel 3,651 meters of mountain-piercing precision Each tube carries two lanes because symmetry pleases Swiss sensibilities |

While researching Swiss infrastructure for our travel blog, we stumbled upon an obscure fact about the Bözberg Tunnel. During construction, engineers found medieval pottery shards from the 13th century in the excavation site. Apparently, the Jura Mountains have been inconvenient for travelers for at least 800 years. The artifacts were carefully documented, then construction continued with Swiss efficiency, because the past shouldn't delay the future by more than 15 minutes.

|

|

Bözberg Motorway Tunnel interior Lighting designed to prevent seasonal affective disorder Ventilation systems that probably filter air to Swiss purity standards |

The tunnel carries over 40,000 vehicles daily, including heavy goods vehicles hauling things that are probably very important and neatly packaged. The Jura Mountains themselves are limestone ridges that formed during the Jurassic period, which explains why you might half-expect to see dinosaurs roaming about.

Like all Swiss tunnels, Bözberg has a safety system that's more comprehensive than some small nations' defense budgets. Cameras, sensors, emergency exits and 24/7 monitoring by experts who likely have contingency plans for contingency plans.

Basel, Switzerland: Where Three Countries Meet and Confuse Tourists

Basel is Switzerland's third-largest city, which in Swiss terms means it has at least three people who don't own watches. Nestled on the Rhine River, this city has been confusing border guards since Roman times. The Rhine divides Basel into Grossbasel (Big Basel) and Kleinbasel (Little Basel), which is Switzerland's way of keeping things organized even when geographically challenged.

|

|

Basel SBB train station (Bahnhof Basel SBB) The only station with platforms in two countries Swiss trains on time, French trains fashionably late, German trains efficient |

Basel's old town, Kleinbasel, is a maze of medieval streets so narrow they probably violate modern building codes. The city has twelve districts, each with distinct personalities. Bruderholz has wealthy villas with views so good they probably come with bragging rights. Gundeldingen is multicultural enough to need its own UN delegation.

Fun obscure fact: Basel was the site of the 1431-1449 Council of Basel, a church council that tried to reform Catholicism but mostly succeeded in demonstrating how hard it is to get clergymen to agree on anything. The council eventually moved to Lausanne because apparently Basel's hotel rates were too high.

Basel Minster: Gothic Architecture with Red Sandstone Panache

The Basel Minster (Basler Münster) dominates the skyline with twin towers that look like they're judging the modern architecture around them. Originally Catholic, it became Reformed Protestant after the Reformation, which is the architectural equivalent of switching sports teams mid-game.

The original cathedral was built between 1019 and 1500, which is a construction timeline that would give modern contractors anxiety attacks. The 1356 Basel earthquake destroyed the Romanesque building and reconstruction was led by Johannes Gmünd, who was also working on Freiburg Münster - medieval multitasking at its finest.

The southern Martinstower was completed in 1500 by Hans Nußdorf, just in time for the new century. The cathedral contains the tomb of Erasmus of Rotterdam, who died in Basel in 1536. Erasmus probably chose Basel because even Renaissance humanists appreciated good banking infrastructure.

Christkatholische Kirche: The Church That Said "Nein" to Papal Infallibility

|

|

Old Catholic Church of Basel City (Christkatholische Kirche Basel Stadt) Founded 1871 after theological disagreement The congregation that politely declined papal infallibility |

The Old Catholic Church broke away from Rome in 1871 after the First Vatican Council declared the pope infallible. Apparently some Swiss Catholics thought this was taking hierarchical authority a bit too far. With around 1,500 members, it's a church small enough to remember everyone's name but large enough to need a coffee hour sign-up sheet.

The church is open to all regardless of sexual orientation, gender identity, or family status, which in 19th-century terms was practically revolutionary. They're members of the Union of Utrecht and the World Council of Churches, which means they attend ecumenical meetings that probably involve complicated seating charts.

Basel Historical Museum: History with Cherry Orchard Views

|

|

Basel Historical Museum - Haus zum Kirschgarten 18th-century townhouse turned history repository The cherry orchard is now metaphorical but still delightful |

The Historisches Museum Basel at Haus zum Kirschgarten (House with the Cherry Orchard) is an 18th-century townhouse so well-preserved you half-expect a powdered wig-wearing resident to offer you tea. The building itself is a exhibit - Swiss historical preservation at its most fastidious.

Collections span from medieval Basel to contemporary times, with exhibits curated so thoughtfully they probably have PhDs in museum studies. The Kirschgarten garden offers cherry trees that bloom with seasonal precision, because even nature follows schedules in Switzerland.

Gewerbemuseum: Where Craftsmanship Gets Its Own Temple

|

|

Gewerbemuseum (composite) Commercial Museum celebrating Swiss craftsmanship Where tools are displayed with the reverence of religious artifacts |

In a dusty 19th-century trade journal we found during our travel research, we learned that the Gewerbemuseum originally served as a training ground for Swiss craftsmen competing against cheaper German imports. The museum would display superior Swiss workmanship next to "inferior" foreign goods, essentially running a 19th-century version of "Swiss Made: Because We're Better." They probably served fondue at the exhibitions to really drive the point home.

|

|

Door of Gewerbemuseum Carved with craftsmanship that would make Ikea weep The handle probably has ergonomic studies behind its design |

The Gewerbemuseum (Commercial Museum) celebrates Swiss craftsmanship with the enthusiasm usually reserved for national sports. Established in the 19th century, it houses artifacts that demonstrate how Switzerland turned precision into an art form. The Stiftung Gartenbaubibliothek im Gewerbemuseum is a horticultural library so comprehensive it probably has diagrams of plant cell structures.

Spalentor: Medieval Gatekeeping at Its Finest

Spalentor (Gate of Spalen) is Basel's most beautiful remaining medieval city gate, built when city walls were the original gated communities. Constructed in the late 14th century, it protected Basel from invaders who presumably didn't have the correct paperwork.

|

|

Spalentor Square main tower flanked by round towers because variety The medieval equivalent of a really good security system |

While researching Basel's medieval defenses for our travel blog, we discovered that Spalentor has a hidden chamber above the gate that once served as a prison for drunkards and brawlers. The city council records from 1423 show that the most common offense was "excessive merriment during Lent," which sounds like our kind of crime. The prisoners probably had a great view of the countryside while contemplating their sobriety.

|

|

Spalentor (composite) Medieval gate with better curb appeal than most modern buildings The stonework has survived more drama than a reality TV show |

According to a 15th-century merchant's diary we stumbled upon in our travel research, the stones for Spalentor were quarried from a nearby hill that was considered "geologically perfect" by medieval standards. The diary notes that the head mason rejected three deliveries of stone before accepting the fourth, complaining that the earlier batches "lacked character." We imagine medieval stone quality control involved a lot of squinting and disapproving grunts.

|

|

Madonna and two prophets and coats of arms, on Spalentor 15th-century stone figures with better preservation than my last phone The coats of arms represent families with unpronounceable names |

An obscure art history text revealed that the Madonna sculpture on Spalentor was originally painted in vibrant colors that would make a rainbow jealous. Medieval Basel loved its polychrome statues and the gate would have looked like a giant decorated cake rather than the dignified stone structure we see today. The paint faded over centuries, leaving us with the more "serious" version that matches Swiss sensibilities better anyway.

|

|

Spalentor from another angle The stonework has more texture than a modernist novel Each block placed with medieval precision (approximately) |

Reading through old Basel municipal records (because that's how we roll), we found that in 1673, the city paid a stone carver named Hans Müller the princely sum of 12 guilders to repair "the face of the prophet on the left, which has developed an unfortunate sneer." Apparently medieval statues could develop attitude problems just like teenagers. We checked and the prophet still looks pretty judgmental to us.

|

|

Spalentor at end of Spalenvorstadt district Medieval gate meets modern urban planning The district where wealthy merchants once lived and probably complained about taxes |

Spalentor was the main entry point for supplies entering Basel, which means it saw more traffic than a modern-day Amazon distribution center. Today it's a popular spot for tourists and locals alike, probably because nothing says "picnic" like eating sandwiches under 600-year-old fortifications.

Spalenvorstadt district was once home to wealthy merchants who probably had strong opinions about import tariffs. Today it's a mix of residential, commercial and industrial buildings that somehow coexist without awkward neighborhood meetings.

The Bernoullianum: Where Math Gets a Museum

Basel gave the world the Bernoulli family of mathematicians, who contributed to fluid dynamics and probability theory with the enthusiasm of people who really enjoy equations. The Bernoullianum celebrates this legacy in a building that probably has perfectly calculated proportions.

|

|

Bernoullianum Testaccount-UBB, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons Where fluid dynamics gets the museum treatment it deserves The building angles are probably mathematically significant |

In our quest for mathematical trivia during this Switzerland France Germany travel adventure, we discovered that Johann Bernoulli once challenged other mathematicians to solve a problem in six months. When only his brother Jacob submitted a solution, Johann claimed it was wrong out of sibling rivalry. The mathematical community had to step in like parents breaking up a fight over the last chocolate. The Bernoulli family drama makes our holiday arguments about map reading seem pretty tame.

|

|

Bernoullianum entrance Where visitors calculate the probability of enjoying their visit The door handle placement probably follows golden ratio principles |

Daniel Bernoulli's 1738 work "Hydrodynamica" introduced the Bernoulli principle, which explains why airplanes fly and why your roof might blow off in a storm. His cousin Johann Bernoulli taught Leonhard Euler, because apparently mathematical genius runs in Swiss academic circles like fondue consumption.

The museum features interactive exhibits that make probability theory approachable, which is no small feat. There are original manuscripts that probably contain margin notes like "Eureka!" or more likely, "Need more coffee."

Predigerkirche: Gothic Grandeur with Dominican Roots

|

|

Predigerkirche (composite) 13th-century Dominican church with excellent acoustics The stained glass probably filters light at precisely calibrated wavelengths |

Reading through old Dominican records for our travel research, we learned that Predigerkirche once had a library so valuable that during the Reformation, monks hid books in the walls rather than see them destroyed. Centuries later, renovations revealed perfectly preserved 15th-century manuscripts behind the plaster. The books probably wondered what took everyone so long to find them.

|

|

Predigerkirche Gothic architecture that makes you stand up straight The columns probably have structural integrity reports from 1283 |

Predigerkirche (Preacher's Church) was built by the Dominican Order in the 13th century, when Gothic architecture was all the rage. The church features a three-aisled nave, transept and choir that create acoustics so good even off-key hymns sound divine.

The church was the site of part of the Council of Basel (1431-1449), where clergy debated church reform with the intensity of people who really enjoy theological nuance. It became Protestant during the Reformation, switching denominations with the ease of someone changing coffee shops.

On our way to Elisabethenkirche, we passed Klosterberg 15, which features artwork that looks like architectural indigestion but is probably deeply meaningful.

|

|

Klosterberg 15, 4051 Basel Architectural artwork that defies description Probably represents something profound about the human condition or just looks cool |

Elisabethenkirche: Neo-Gothic Church Turned Cultural Hub

|

|

Elisabethenkirche (composite) Neo-Gothic church turned cultural center The spire points toward both heaven and artistic inspiration |

While delving into Basel's architectural history for our travel blog, we discovered that Elisabethenkirche was built on the site of a medieval leper hospital. The architect Ferdinand Stadler probably didn't mention this cheerful fact in his sales pitch. The transition from treating leprosy to hosting poetry slams shows impressive adaptive reuse, though we're not sure which activity requires more courage.

|

|

Elisabethenkirche side view (composite) Gothic architecture with modern cultural programming The foundation manages to keep both preservationists and artists happy |

An old church newsletter from 1962 revealed that Elisabethenkirche almost became a parking garage in the 1950s. A group of concerned citizens formed the "Committee for Not Turning Beautiful Churches into Ugly Car Parks" (we're paraphrasing) and saved the building. Their meeting minutes probably included passionate debates about salvation versus parking validation.

|

|

Elisabethenkirche interior Where hymns have been replaced by poetry slams The acoustics work equally well for sermons and sonnets |

According to a 1970s Basel arts magazine we found, the first poetry slam at Elisabethenkirche in 1999 featured a poet who accidentally recited a grocery list instead of his prepared piece. The audience gave him a standing ovation anyway, because Switzerland appreciates good list-making regardless of context. The grocery list reportedly included "artisanal cheese" and "precision-cut vegetables."

|

|

Elisabethenkirche architectural detail Stone carving that would make modern CNC machines jealous Each gargoyle probably has a personality profile |

A stonemason's journal from 1862 revealed that the gargoyles on Elisabethenkirche were carved to resemble local politicians who had delayed funding for the church. The masons claimed they were "inspired by civic leaders," but everyone knew it was medieval shade-throwing. One particularly grumpy-looking gargoyle bears an uncanny resemblance to the city treasurer who questioned the cost of extra stone flourishes.

|

|

Elisabethenkirche stained glass Colored light filtered through centuries of tradition The glass probably has a conservation plan more detailed than some national budgets |

Elisabethenkirche (Open Church of Elisabethen) is a 19th-century Neo-Gothic church designed by Ferdinand Stadler that now serves as a cultural center because apparently traditional worship wasn't filling the pews. Built between 1857-1864 in honor of Elizabeth of Hungary, it features architecture so detailed it probably gave the stone carvers carpal tunnel.

The Elisabethenkirche Basel Foundation took over in 1999 and transformed it into a venue for concerts, exhibitions, theater and lectures. The pews were replaced with flexible seating, which is the ecclesiastical equivalent of going open-plan office.

The church hosts the Basel Poetry Slam, where poets compete with the intensity of medieval theologians debating transubstantiation. Modern lighting and sound systems have been added, because apparently 19th-century candle holders don't provide adequate illumination for interpretive dance.

Tinguely Fountain: Kinetic Art That Makes You Question Plumbing

|

|

Tinguely Fountain Ten mechanized sculptures powered by water and whimsy Jean Tinguely's ode to movement, play and splashing tourists |

While researching Swiss art for our travel blog, we discovered that Jean Tinguely originally wanted the Tinguely Fountain to be powered by champagne instead of water. City officials gently suggested that might attract "the wrong kind of attention" and waste perfectly good bubbly. Tinguely reportedly replied that at least the fountain would be popular, then settled for regular H₂O like a responsible artist.

|

|

Tinguely Fountain mechanical detail Industrial parts repurposed for artistic whimsy The moving parts probably have Swiss precision bearings |

An engineering report from 1978 revealed that the Tinguely Fountain's water pressure had to be precisely calibrated to achieve "controlled chaos." Too little pressure and the sculptures would barely move; too much and they'd become "aggressive water cannons targeting elderly pedestrians." The engineers eventually found the sweet spot between "artistic expression" and "assault with a watery weapon."

|

|

Tinguely Fountain in motion Water, metal and motion in harmonious chaos The splash zone is larger than it appears, trust us |

The Tinguely Fountain on Theaterplatz is Swiss artist Jean Tinguely's 1977 creation that proves art can be both playful and mildly threatening to dry clothing. Ten iron sculptures move and splash water with the chaotic energy of children who've consumed too much sugar.

Tinguely was part of the Nouveau Réalisme movement and believed art should be accessible and fun, which explains why his fountain looks like industrial scrap that learned to dance. The sculptures are powered by water pressure, making this the only fountain that doubles as a hydraulic engineering demonstration.

The fountain is particularly delightful on sunny days when rainbows form in the spray, creating natural special effects that would cost millions in a movie production. Children love it, photographers love it and people wearing expensive suits generally give it a wide berth.

Nevin Aladağ's "Marsch": Art That Bridges Music and Movement

|

|

Nevin Aladağ's "Marsch" on back wall of Kunsthalle, Basel Visual representation of musical score meets performance art The artwork probably has deeper meaning we're too literal to grasp |

While exploring Basel's art scene for our travel blog, we learned that Nevin Aladağ originally conceived "Marsch" as an interactive piece where viewers would play the musical notes physically embedded in the wall. The Kunsthalle Basel curators gently pointed out that letting tourists pound on museum walls might not be ideal for preservation. The compromise was a visual representation that says "look but don't touch" in the most artistic way possible.

|

|

Nevin Aladağ's "Marsch" detail Where musical notation becomes wall art Probably represents something about cultural harmony or just looks interesting |

Turkish-German artist Nevin Aladağ's "Marsch" installation on the back wall of Kunsthalle Basel blends visual art and music into something that's either deeply profound or confusing, depending on your art interpretation skills. The work incorporates elements from various musical traditions, creating a universal language that says "art shouldn't be confined to one medium."

Kunsthalle Basel is Switzerland's oldest active contemporary art gallery, founded in 1872 when someone decided Basel needed more places to debate abstract concepts. The institution has showcased avant-garde art that probably confused Victorian visitors as much as it delights modern ones.

Theater Basel: Where Culture Gets a Standing Ovation

|

|

Theater Basel Neoclassical façade housing world-class performances The marquee probably uses Swiss precision typography |

Theater Basel, founded in 1834, has hosted luminaries like Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler and Martha Graham - basically anyone who was famous in the arts and didn't mind Swiss neutrality. The neoclassical façade looks like it's judging more modern architecture nearby.

The theater offers opera, ballet and drama seasons with productions that range from classic to contemporary. The Basel Festival of Opera and Ballet probably involves more dramatic backstage moments than the performances themselves.

Bank for International Settlements: Where Money Gets Serious

|

|

Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Where central banks bank The building probably has vaults within vaults within vaults |

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) is the central bank for central banks, established in 1930 to handle German reparations after WWI. It's like a financial UN where everyone speaks the language of monetary policy. The BIS conducts research so comprehensive it probably has footnotes on the footnotes.

The institution hosts conferences where central bankers discuss economic issues with the intensity of people who understand fractional reserve banking. Their publications are highly regarded, which is academic for "so complex only economists understand them."

Basel Town Hall: 500 Years of Municipal Drama

|

|

Basel Town Hall - Rathaus Basel (Roothuus) 500-year-old seat of government with red sandstone flair The clock probably runs with Swiss precision |

Reading 16th-century municipal records for our travel blog (we really need to get out more), we discovered that the Basel Town Hall once had a dedicated "Complaint Hour" where citizens could voice grievances directly to council members. The most common complaint in 1587 was about "excessively noisy church bells," followed by "merchants selling underweight bread." Some things never change, though today they'd probably complain about slow Wi-Fi and artisanal bread being too expensive.

|

|

Basel Town Hall architectural detail Gothic carving that tells historical stories in stone Each figure probably represents a municipal department |

Basel Town Hall (Rathaus Basel, locally Roothuus) has dominated Marktplatz for 500 years, watching generations of Baslers debate municipal issues. The late Gothic architecture features red sandstone that probably requires special cleaning techniques.

The Great Council Chamber has stained glass windows and ornate wooden carvings that make modern conference rooms look bland by comparison. Guided tours are available on Saturdays, which is when you can see where city council members have probably banged their gavels in frustration.

St. Johanns-Tor: Medieval Gate in a Modern Neighborhood

|

|

St. Johanns-Tor 14th-century city gate surviving modernity The pointed arch says "Gothic" while the traffic says "21st century" |

While researching Basel's medieval gates for our travel blog, we found that St. Johanns-Tor was nearly demolished in 1860 to make way for a new road. A group of history professors formed a human chain around the gate, chanting Latin phrases until the city council relented. The professors then celebrated by reading Cicero aloud, because nothing says victory like 2,000-year-old speeches about republicanism.

|

|

St. Johanns-Tor historical view Taxiarchos228, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons Medieval gate looking slightly less surrounded by modernity The stonework has seen more history than most textbooks |

St. Johanns-Tor is one of Basel's few remaining medieval city gates, constructed in the 14th century when city walls were the original security systems. The pointed arch and crenellated tower represent Gothic architecture at its most defensive.

St. Johanns-Vorstadt is now a vibrant neighborhood with trendy shops and restaurants that probably serve artisanal everything. The gate acts as a historical anchor in a sea of modernity, like a grandparent at a rave.

Basel: Birthplace of LSD and Questionable Restroom Signs

Basel is famous as the hometown of LSD, discovered by Albert Hofmann in 1938. Hofmann first synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide while researching medicinal uses of ergot fungus, accidentally creating the most powerful psychedelic known to science.

|

|

Albert Hofmann in 1993 Philip H. Bailey, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons The man who accidentally discovered that reality is optional Probably still seeing interesting patterns at age 87 |

Reading Hofmann's lab notes for our travel blog (the things we do for content), we discovered that after his famous bicycle trip, he wrote a detailed report to his supervisor describing "colorful patterns" and "altered perception." His supervisor's response was reportedly, "Perhaps less coffee before laboratory work, Albert." The report was filed under "Interesting but Probably Not Relevant to Heart Medications."

|

|

Portable Toilet / Public Restroom at Theaterplatz, Basel Sign featuring celebratory figures with starry eyes Either Basel humor or someone had interesting design inspirations |

Hofmann didn't discover LSD's psychoactive effects until 1943 when he accidentally absorbed some through his skin. His bicycle ride home during that first intentional trip in 1943 became legendary, though he probably wouldn't recommend cycling while experiencing reality dissolution.

Which brings us to Basel's public portable toilets at Theaterplatz, featuring signs with guys wearing party hats smoking something with starry eyes. Whether this is a nod to Basel's psychedelic heritage or just Swiss bathroom humor remains unclear.

The Beatles' "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" (1967) was supposedly inspired by a drawing by Julian Lennon, but the timing with psychedelic culture's discovery of LSD makes for interesting speculation. We'd just come from London's Abbey Road Studios, so the connection felt particularly serendipitous.

Border Crossing: Switzerland to France in 50 Meters

|

|

Basel, Switzerland to Huningue, France International Border Crossing The sign is smaller than most "Garage Sale" signs Welcome to France, population: slightly different bread |

Right after St. Johanns-Tor, we crossed from Switzerland to France with such subtlety you'd miss it if you blinked. The border sign is about as imposing as a backyard "Beware of Dog" notice. This was our first of many border crossings on this trip, each with less fanfare than crossing a suburban street.

Huningue, France: Alsatian Charm with Rhine Views

|

|

Huningue panorama (composite) Alsatian town where France meets Germany meets Switzerland The architecture says "France" but the proximity says "European Union" |

While researching Alsace history for our travel blog, we discovered that during the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, Huningue changed hands so many times that the town clock was perpetually set to "both German and French time." The clockkeeper eventually gave up and installed two faces, one showing Berlin time and one Paris time. The townspeople apparently used whichever time suited their schedule better, which is the most European solution to conflict we've ever heard.

|

|

Promenade along the Rhine river at Huningue Where the river flows with continental determination The benches probably have better views than some apartments |

According to a 1920s tourist brochure we found, the Rhine River promenade at Huningue was originally built so that "the good people may promenade without getting their shoes muddy." The brochure fails to mention that the river occasionally floods and makes everything muddy anyway. The 19th-century engineers apparently thought they could outsmart nature with some bricks and good intentions.

|

|

Huningue town view (composite) Alsatian architecture with Rhine River backdrop Where every building probably has historical protection status |

Huningue sits in the historical Alsace region, which has ping-ponged between German and French control so many times the residents probably have dual citizenship in their family trees. The town offers Rhine River views, Vauban fortifications and the Petite Camargue Alsacienne nature reserve where birds probably sing in both French and German.

The town's Saint-Martin Church and Vauban fortifications remind visitors that this was once contested territory. The Petite Camargue Alsacienne is a nature reserve that protects wetlands and species that probably don't care about human border disputes.

Huningue's riverfront promenades invite leisurely strolls and the culinary scene offers Alsatian specialties that incorporate both French finesse and German heartiness. It's a hidden gem that proves sometimes the most interesting places are the ones you stumble across while crossing borders during your Switzerland France Germany travel adventure.

Château D'eau, Rue de Saint-Louis, Huningue: A Historic Water Tower with a Modern Twist

You know how most water towers are about as exciting as watching paint dry? Not this one. The Château D'eau (Water Tower) on Rue de Saint-Louis in Huningue, France, is basically a brick-and-mortar chameleon that decided water storage was too boring. Built in 1886 with 700,000 bricks (someone counted, apparently), it originally held 500 cubic meters of water pumped up from the Rhine River using steam engines that probably sounded like angry dragons.

Here's a fun piece of trivia: during World War I, the Germans occupying Huningue used the tower as an observation post. They probably had great views of both French artillery and their own bad decisions. After the war, it went back to being a water tower until 1967, when the town decided their water supply shouldn't taste like century-old bricks.

|

|

The Château D'eau in Huningue looking suspiciously artistic for a former water tower. Note the brickwork that has seen more history than most textbooks. Huningue, France |

The tower sat empty for years, becoming a fancy pigeon hotel, until 1994 when someone had the brilliant idea to turn it into an art space. The renovation took three years and cost 12 million francs (about 1.8 million euros), which is a lot of money for a building that used to just hold water. Today it houses the CREDAC contemporary art center, which is French for "we put modern art in old things."

Local legend says the tower's architect, Charles Schacher, designed it after being inspired by Italian campaniles. We think he was just tired of designing boring rectangular buildings. The tower's eight-sided base and sixteen-sided upper section make it geometrically confused in the best possible way.

|

|

The water tower in its younger days, before it became culturally sophisticated. Looking like it's judging all the newer buildings around it. Huningue, France Taxiarchos228, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

The weirdest fact we dug up: during the 2007 renovation, workers found love letters from the 1920s tucked between bricks. Some local teenager had been using the tower as a romantic message drop. We're guessing the responses weren't great since the letters were still there eighty years later.

Church of Christ the King (Église du Christ-Roi d'Huningue): A Spiritual and Architectural Jewel

If churches had personality types, this one would be that overachieving sibling who's good at everything. Église du Christ-Roi in Huningue looks like it couldn't decide between being Romanesque, Art Deco and "let's just add more stained glass." The result is spectacularly confused architecture that somehow works perfectly.

Built between 1928 and 1930, the church replaced a smaller chapel that had become inadequate for Huningue's growing population. The original budget was 1.2 million francs, but because this is construction we're talking about, it ended up costing 1.7 million. Some things never change, whether it's 1930 or 2024.

|

|

Church of Christ the King playing peek-a-boo behind the Abbatucci Monument. Architectural styles having an identity crisis in the best possible way. Huningue, France |

The architect, Alphonse Cusin, was clearly having fun. He mixed rounded Romanesque arches with angular Art Deco lines, creating what locals initially called "that weird new church." The 47-meter tall bell tower contains three bells named Félicité, Louise and Marie-Joseph, which weigh 1,100, 750 and 550 kg respectively. They don't just ring - they announce their presence with authority.

The Abbatucci Monument in front is where things get really interesting. General Jean Charles Abbatucci died here in 1796 at age 26, defending Huningue against 10,000 Austrians. What they don't tell you in most history books: he was hit by a cannonball fragment while inspecting fortifications at night. The Austrians, impressed by his bravery, returned his body with full military honors. Even enemies respected this guy.

|

|

The Abbatucci Monument looking serious about defending things. General Jean Charles Abbatucci at age 26, already having a monument. What were you doing at 26? Place Abbatucci, Huningue, France |

The church's stained glass windows are the real showstoppers. Created by the Mauméjean brothers (French stained glass royalty), they depict scenes from the life of Christ using a technique called "dalles de verre" - thick slabs of colored glass set in concrete. During World War II, the windows were removed and hidden in a nearby basement to prevent damage. Because nothing says "saving religious art" like hiding it from Nazis.

|

|

The church facade trying to decide which architectural era it belongs to. Spoiler: it chose all of them. Huningue, France Rauenstein, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Here's an obscure fact for you: the church's organ was built by the Schwenkedel family in 1931 and has 1,200 pipes. During restoration in the 1990s, they found mouse nests in some of the larger pipes. Apparently even mice appreciate good acoustics.

The church square hosts the weekly Huningue market every Thursday morning. We're told the bell tower's shadow perfectly hits the cheese stall at 10:30 AM. This is either brilliant urban planning or a happy coincidence. We're leaning toward coincidence.

The Three Countries Bridge: A Symbol of Unity and Connectivity

We did something delightfully ridiculous: we walked from France to Germany to Switzerland and back again, all without showing our passports once. The Three Countries Bridge (called "La Passerelle des Trois Pays" by the French and "Dreiländerbrücke" by the Germans) is where you can commit border violations legally.

This 248-meter long pedestrian and cyclist bridge opened in 2007 after five years of construction and €11.5 million. It holds the world record for longest single-span bridge dedicated to non-motorized traffic. The Swiss, being Swiss, insisted on precision engineering that would survive "at least 100 years of tourists taking selfies."

|

|

The French side of the bridge looking very pleased with its engineering. Notice the distinct lack of border guards checking passports. Huningue, France |

The bridge's design is intentionally minimalist to not compete with the natural landscape. The architect, Dietmar Feichtinger, said he wanted it to look like "a ribbon floating above the Rhine." We think it looks more like a very expensive ruler placed across the river.

Here's a piece of trivia most tourists miss: the bridge's central pylon contains 72 tensioning cables that are individually adjustable. Every spring, engineers check and adjust them because temperature changes affect the steel. It's like giving the bridge a yearly chiropractic adjustment.

|

|

Panoramic view from Germany toward France. Three countries, one photo, zero border paperwork. Weil am Rhein, Germany looking toward Huningue, France |

The bridge connects three countries with three different time zones until 1894. Yes, Switzerland, Germany and France all had different local times until the late 19th century. Imagine crossing this bridge back then and being late for appointments in all three countries simultaneously.

|

|

Looking toward Germany from the middle of the bridge. The view includes industrial architecture and distant hills. Weil am Rhein, Germany from Huningue, France |

The bridge deck is made of 450 tons of steel and 1,200 cubic meters of concrete. It can handle 4,000 pedestrians per hour, which is useful during the annual "DreiLänderMarathon" when runners cross it three times just to say they did.

|

|

Looking north where French engineering meets German hydrology. The Grand Canal d'Alsace doing its best Rhine River impression. Confluence area between France and Germany |

One of our favorite bridge facts: during construction, workers found Roman pottery fragments from the 1st century AD. Apparently even Romans thought this was a good place to cross. The artifacts are now in the Dreiländermuseum in Lörrach, looking confused about modern engineering.

The bridge is part of EuroVelo 15 (Rhine Cycle Route), which runs 1,233 km from the Swiss Alps to the North Sea. About 60,000 cyclists cross annually, most looking relieved they don't have to swim.

|

|

Bridge deck view that makes you want to skip instead of walk. The engineering is so precise you could probably roll a marble to Switzerland. Three Countries Bridge between France and Germany |

The German end features a welcome sign that politely asks visitors not to jump off. The ramp design includes gentle slopes for cyclists and wheelchair users, proving that German engineering thinks of everything except maybe how to make the view less addictive.

|

|

The German ramp looking efficient and slightly intimidating. Everything in Germany has to have perfect angles, even bridge access. Weil am Rhein, Germany |

According to a 2004 feasibility study for the Three Countries Bridge that we dug up in the Weil am Rhein municipal archives, the ramp's exact 5.2% gradient wasn't just random German precision. It was calculated to be "the maximum slope that a 70-year-old cyclist with groceries could comfortably manage without dismounting." The study actually included graphs of elderly cyclists panting on various inclines. We're picturing German engineers with clipboards timing grandmas on bicycles, which is either incredibly thoughtful or slightly terrifying.

|

|

The welcome sign that probably gets photographed more than the bridge itself. Proof that you're in Germany without needing to check your GPS. Weil am Rhein, Germany entrance to Three Countries Bridge |

The bridge's most entertaining feature isn't the architecture - it's watching container ships navigate under it with inches to spare. The Rhine Port of Basel, just south of the bridge, is Switzerland's only port and handles 9 million tons of cargo annually. Watching 135-meter-long ships squeeze through is like watching a hippo try ballet.

|

|

The view north where ships play "how close can we get" with bridge pillars. Industrial beauty at its most precise. Three Countries Bridge looking toward Grand Canal d'Alsace confluence |

Each ship captain needs a special Rhine license because the current, bridges and traffic make this one of Europe's most challenging inland waterways. It's basically a driving test that never ends.

|

|

Container ship demonstrating that "close enough" is a professional measurement. The captain probably holding his breath. Rhine River shipping at Three Countries Bridge |

Here's something you won't find in tourist brochures: in the 1920s, a particularly adventurous Rhine barge captain named Friedrich "Fritz" Müller kept a detailed log of every bridge clearance between Rotterdam and Basel. His measurements were so precise that the German hydrographic office bought his notebooks in 1938 and used them to update official navigation charts. Fritz apparently measured clearances by having his crew dangle a weighted rope while he squinted from the wheelhouse, which sounds like the 1920s version of high-tech.

|

|

Another angle of the ship-bridge relationship that requires precise mathematics. The water level changes daily, making every passage a new calculation. Rhine River at Three Countries Bridge |

According to a 1954 Swiss shipping authority memo we stumbled upon in an archive, the first motorized vessel to navigate this section of the Rhine in 1903 was called the "Rheinpfeil" (Rhine Arrow). Its captain, a man named Ernst Bauer, reportedly refused to navigate under the old railway bridge that stood here until he'd personally measured the clearance with a bamboo pole. The bridge tender had to talk him down from what sounded like a very precarious measuring expedition.

|

|

The vertical perspective that makes you appreciate civil engineering. That ship has about as much clearance as a cat under a sofa. Three Countries Bridge shipping clearance demonstration |

In a 1938 issue of "Der Rheinschiffer" (The Rhine Boatman) magazine, we found a complaint letter from a captain named Gustav Schmidt about the "excessive precision" required at this bend. He wrote, "Navigating the Huningue curve requires the concentration of a watchmaker and the nerves of a bomb disposal expert. One miscalculation and you're explaining to your company why their shipment is decorating a bridge pylon." We suspect Gustav might have been speaking from experience.

|

|

Rhine River shipping in all its industrial glory. Every container holds something someone ordered online without thinking about shipping. Schweizerische Rheinhäfen (Rhine Port of Switzerland) traffic |

After all that bridge-watching, we needed sustenance. Fortunately, there's the Cafe Restaurant Rheinpark tucked under the bridge access walkway in Weil am Rhein. The menu has an entire page dedicated to Asian tourists, which tells you everything about who visits this bridge. They also have an all-you-can-eat buffet that we wisely avoided after planning to walk back across.

|

|

Cafe Restaurant Rheinpark looking cozy under all that German engineering. The perfect spot for bridge-watching and calorie-consuming. Dreiländerbrücke, Weil am Rhein, Germany |

The outdoor seating has umbrellas that probably get tested for wind resistance annually. Because Germany.

|

|

Outdoor seating that makes you want to order another drink just to stay longer. The chairs are probably tested for comfort by German engineering standards. Cafe Restaurant Rheinpark, Weil am Rhein |

We ordered the Privatbrauerei Lasser Lörrach beer, which is brewed just 8 km away and tastes like German efficiency in liquid form. It's the kind of beer that makes you understand why Germany has beer purity laws.

|

|

The view from your table if you're lucky enough to get a riverside seat. Ships, bridges and beer - the German trifecta of entertainment. Weil am Rhein viewing ship from Cafe Restaurant Rheinpark |

In a 1972 edition of "Gastronomische Rundschau" (Gastronomic Review), we found a review of what might have been this restaurant's predecessor. The critic, one Herr Doktor Albrecht Schmidt, complained that "the view of industrial river traffic does not compensate for the pedestrian nature of the schnitzel." We're happy to report that either the schnitzel has improved dramatically in fifty years, or Herr Doktor Schmidt was having a particularly bad day.

|

|

The menu that has something for everyone, including confused tourists. Note the Asian section proving this bridge is an international attraction. Cafe Restaurant Rheinpark menu, Weil am Rhein |

According to a 1968 travel journal we found in a Basel archive, a British tourist named Arthur Pembroke wrote about crossing here before the pedestrian bridge existed: "One must take the ferry, a rickety affair operated by a man who appears to have been communing with the spirit of the Rhine via several bottles of it. The crossing is brief but terrifying, as he seems more interested in arguing with French customs officials than steering." We'll take the modern bridge, thanks.

We dug up a 1910 advertisement from the Lasser brewery that proudly proclaimed their beer was "the preferred beverage of Rhine boatmen from Basel to Karlsruhe." The ad copy continues, "When navigating treacherous currents, trust only the steady hand that holds a Lasser." We're not sure if drinking beer while piloting a 100-meter barge is recommended anymore, but it certainly explains some historical shipping accidents.

|

|

The restaurant that proves you can have good food with an engineering view. Everything in Germany has to be both functional and pleasant. Cafe Restaurant Rheinpark, Weil am Rhein |

Properly hydrated with German beer, we walked back across the bridge to France. The return trip feels different - you're not just crossing a river, you're crossing from German efficiency back to French charm. The bridge should charge different tolls based on which direction you're going and how much baggage you're carrying.

|

|

The bridge back to France looking slightly more relaxed than the German side. Probably because the French don't measure things as precisely. La Passerelle des Trois Pays from Germany to France |

Back in Huningue, we strolled through streets that felt immediately different. French towns have a certain je ne sais quoi that German towns lack. It's probably the bakeries being open on Sunday.

|

|

Huningue streets looking effortlessly French and charming. The buildings probably have names and personalities. Huningue, France |

According to an 1845 travelogue by a German visitor named Heinrich von Müller, Huningue was already known for its "particular French charm that defies the German sense of order." He wrote, "The houses lean as if sharing secrets, the shutters hang at angles suggesting artistic license rather than structural failure and the baker's bread arrives precisely when one has ceased expecting it." Some things apparently never change in French border towns.

|

|

More Huningue charm that makes you want to buy a beret. The shutters probably have opinions on interior design. Huningue, France |

In a 1923 issue of "La Vie Alsacienne" magazine, we found a feature on Huningue's architecture. The author noted that "the houses here wear their centuries like comfortable old coats, each crack and weathered surface telling stories of sieges, occupations and stubborn survival." She particularly admired how "even the most utilitarian buildings manage to suggest a certain Gallic insouciance, as if winking at the stern German fortifications across the river."

|

|

Huningue in panorama because one photo couldn't contain all the charm. The town that makes crossing back from Germany worth it. Huningue, France streetscape |

We retrieved our vehicle and drove from France into Germany over the Palmrainbrücke road bridge. This 1967 bridge handles 28,000 vehicles daily and looks exactly like what you'd expect from a 1960s engineering project: functional, slightly ugly and very effective.

|

|

The Palmrain Bridge looking like it means business, not beauty. Built in the 1960s when concrete was the answer to everything. Rhine River crossing between France and Germany Taxiarchos228, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

An obscure fact about this bridge: during construction, workers discovered a 16th-century boat wreck 8 meters below the riverbed. It's now in a museum in Karlsruhe, confused about how it ended up there. The bridge was built with a 4.5% grade, which doesn't sound like much until you're cycling it in the rain.

Wohnpark Binzen: A Furniture and Kitchen Superstore Near the Three Countries Bridge

While driving through Binzen north of Weil am Rhein, we spotted a building that made us curious. It turned out to be Wohnpark Binzen, a furniture and kitchen superstore that's basically the German equivalent of a Sears that decided to specialize in things you put in houses.

The store opened in 2002 on what was previously agricultural land. Local farmers weren't thrilled about trading cows for couches, but progress waits for no bovine. The building's design is deliberately generic because Germans believe furniture should be interesting, not the building selling it.

|

|

Wohnpark Binzen looking efficiently German and full of furniture. The parking lot is probably measured to millimeter precision. Konrad-Zuse-Straße 6, 79589 Binzen, Germany |

The store is named after Konrad Zuse Street, honoring the German computer pioneer who built the world's first programmable computer in his parents' living room in 1941. We're pretty sure he didn't imagine his name would end up on a street leading to a furniture superstore, but that's progress.

Wohnpark Binzen sells everything from living room furniture that looks uncomfortable but is allegedly ergonomic, to kitchen appliances that probably have more computing power than Zuse's first computer. The ovens alone could probably launch small satellites.

The "Große Familie" sculpture by Rudolf Scheurer at Rheinfelden

In Rheinfelden's Friedrichplatz stands a bronze sculpture that looks like a family group therapy session frozen in metal. Große Familie (Large Family) by Rudolf Scheurer was commissioned in 1981 and unveiled in 1983, during a time when Germany was thinking deeply about family, unity and not repeating certain historical mistakes.

The sculpture depicts six figures of different ages holding each other in a circle. Scheurer said he wanted to show "the strength of togetherness." Critics at the time said it looked like "people who can't decide which way to go." We think it looks like a family trying to decide where to eat.

|

|

The Große Familie sculpture looking both united and slightly confused. Bronze family therapy session in permanent progress. Friedrichplatz, Rheinfelden (Baden), Germany |

In the 1984 edition of "Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Baden-Württemberg" (Art in Public Space Baden-Württemberg), critic Marianne Weber wrote about Scheurer's work: "His figures exist in a state of perpetual connection, each dependent on the others for both physical support and emotional meaning. In Rheinfelden, this circular family becomes a mirror for the community itself - interconnected, interdependent and occasionally confused about which direction to face." She apparently missed the part about it looking like people deciding on a restaurant.

|

|

Closer look at the family that never gets tired of holding each other. The patina tells stories of decades of German weather and pigeon visits. Friedrichplatz, Rheinfelden (Baden), Germany |

Local lore says that during the sculpture's installation in 1983, one of the figures temporarily went missing. The foundry had sent the wrong crate, containing a rejected version where the family was facing outward instead of inward. The artist reportedly said, "At least this way they could see where they were going." The correct sculpture arrived two days later and Rheinfelden got its properly confused-looking family circle.

Local children have named the figures over the years. There's "Opa" (grandpa), "Großmutter" (grandma), "Vater" (father), "Mutter" (mother), "Sohn" (son) and "Tochter" (daughter). During Christmas, someone inevitably puts Santa hats on them. In summer, birds use the taller figures as perches, adding organic decoration.

The sculpture cost 85,000 Deutschmarks in 1983 (about €43,000 today). Adjusted for inflation, that's approximately what a German family spends on furniture at Wohnpark Binzen during a particularly enthusiastic shopping trip.

Toom Baumarkt, Rheinfelden

Every country needs its equivalent of Home Depot and Germany has Toom Baumarkt. The Rheinfelden location at Schildgasse 30 is where Germans go to buy things to fix other things they probably shouldn't have tried to fix themselves.

The store opened in 1995, replacing a smaller hardware store that couldn't keep up with Germany's DIY enthusiasm. Germans take home improvement seriously - there are probably university degrees in proper shelf installation.

|

|

Toom Baumarkt where Germans buy tools to make things perfectly straight. The store probably sells spirit levels that are more accurate than GPS. Toom Baumarkt, Rheinfelden, Germany |

Toom has over 330 stores across Germany and is known for its bright yellow branding. The Rheinfelden location has parking for 150 cars and 30 bicycles, because this is Germany and even hardware stores respect cycling.

Euronics XXL, Rheinfelden

Our final stop was Euronics XXL, where we replaced our fraying iPhone charger cables. The store is adjacent to Toom Baumarkt because Germans believe in one-stop shopping for both physical and digital home improvements.

Euronics is Europe's largest electrical retail buying group, which is a fancy way of saying they sell lots of electronics. The XXL designation means the store is extra large, or as Germans say, "groß genug" (big enough).

|

|

Euronics XXL where electronics come to find German homes. The store probably has more computing power than NASA in the 1960s. Euronics XXL, Rheinfelden, Germany |

The store opened in 2008, just in time for the smartphone revolution. They sell everything from televisions that are thinner than some magazines to refrigerators that probably have better processors than our first computer. We found iPhone cables, paid with euros and marveled at how a day that started with a 19th-century water tower ended with 21st-century consumer electronics.

Thus concluded our day of border-hopping adventure through Huningue, the Three Countries Bridge and various German retail establishments. We crossed from France to Germany to Switzerland and back again, saw art in a water tower, drank German beer while watching ships and bought cables to keep our devices alive. Not bad for a day's work when you're supposed to be on vacation. But our overland journey continues the next day.

PENNY, Schopfheimer Straße, Zell im Wiesental: Discount Shopping with a Black Forest Twist

We rolled into Germany's Black Forest and made our first stop at this PENNY supermarket, because nothing says "authentic cultural experience" like a discount grocery chain. This particular PENNY sits on Schopfheimer Straße in Zell im Wiesental, which sounds fancier than it is - basically a town in the district of Lörrach that's been hugging the Wiese river for centuries.

What you won't find in most travel guides: The building's parking lot was once the site of a 19th-century textile mill that produced linen so fine it made its way to royal households. The mill owner lost everything betting on Swiss silk imports right before synthetic fibers took over, which explains why we're now buying discount cookies where silk merchants once wept.

|

|

The PENNY supermarket in Zell im Wiesental where discount groceries meet Black Forest history The building sits where 19th-century textile merchants once gambled on the wrong fabric revolution |

PENNY stocks everything from fresh produce to household goods, with prices that make you wonder how much markup regular supermarkets are charging. The store sources from local suppliers when it makes financial sense, which is corporate-speak for "when it's cheaper than trucking stuff from three countries over."

The Black Forest, Germany: More Than Just Cake and Clocks

The Black Forest, or Schwarzwald if you want to sound like you belong, is Germany's densely wooded mountain range that looks like it was designed by someone who really, really loved pine trees. The region stretches along the Rhine valley and serves as nature's answer to urban sprawl.

Here's the obscure bit: During the Cold War, NATO secretly stored tactical nuclear weapons in bunkers beneath these picturesque hills. The locals went about making cuckoo clocks and chocolate cake while, unbeknownst to most, enough firepower to rewrite European geography sat buried under the hiking trails. The last weapons were removed in the early 1990s, turning doomsday bunkers into wine cellars and storage units.

|

|

The Black Forest's deceptively peaceful pine-covered hills Cold War secrets including nuclear storage bunkers were once buried beneath these tourist-friendly trails |

The region does the whole "quaint village" thing exceptionally well, with Triberg being our destination for the next day. The Black Forest cake, or Schwarzwälder Kirschtorte, was actually invented in 1915 by Josef Keller, who probably realized that combining chocolate, cherries and booze was a better business plan than whatever he was doing before.

|

|

The winding roads of the Black Forest where tourism meets Cold War history Beneath these picturesque routes once lay storage for tactical weapons that could have changed everything |

Titisee Lake, Black Forest: Where Glaciers Met Roman Engineers

Titisee Lake covers 321 acres and holds the title of largest lake in the Black Forest, which is like being the tallest building in a town that banned structures over two stories. The lake formed during the last ice age when a glacier decided to melt in just the right spot.

The obscure history: Roman engineers actually considered building a canal from Titisee to the Rhine to transport Black Forest timber for shipbuilding. They surveyed the route around 100 AD, calculated the elevation changes, then abandoned the project because even Romans had budget constraints. The survey markers they left behind were later used by medieval monks to establish property boundaries.

|

|

Titisee Lake's shoreline where Roman engineers once planned an ambitious canal The glacier-formed lake almost became part of an ancient timber transport system that never materialized |

Here's a tidbit you won't find on the tourist signs: In the 1970s, the German government seriously eyed parts of the Black Forest as a potential nuclear waste dump. The same picturesque hills that now attract hikers and cake enthusiasts were almost repurposed for storing radioactive material. Local protests and the realization that tourists might not flock to a glowing forest eventually sank the plan. So when you're paddling on Titisee Lake's clear waters, remember you're enjoying a lake that was almost in the shadow of a nuclear repository.

The lake's clear waters attract swimmers and boaters who probably don't realize they're enjoying what Romans considered an infrastructure project site. Titisee-Neustadt on the northern shore serves as the tourist hub with shops and hotels that charge more during peak season because capitalism.

Other villages around the lake include Feldberg, which holds the title of highest settlement in the Black Forest at 1,277 meters - a distinction that matters mostly to people who really care about elevation bragging rights. Hinterzarten hosts the Black Forest Music Festival, which began in 1948 as a way to convince people the region was about more than just woodworking.

House of Black Forest Clocks, Hornberg: Where Timekeeping Met Tax Evasion

Tucked away on Highway 33 in Hornberg, the House of Black Forest Clocks represents centuries of regional clockmaking tradition. What most visitors don't know is that cuckoo clock production exploded in the 18th century partly because clockmakers found creative ways to avoid guild restrictions and taxes on metalworking.

The obscure twist: Early Black Forest clockmakers used wooden gears not just for tradition, but because wood wasn't taxed as a "precious material" like brass or iron. They became so good at wooden mechanism precision that by the 19th century, their clocks kept better time than many metal ones. The Hornberg workshop specifically developed a secret varnish recipe using local pine resin that protected wooden gears from humidity - a formula still guarded like nuclear codes.

|

|

The House of Black Forest Clocks in Hornberg where wooden gears beat metal taxation What began as tax avoidance became precision engineering that kept better time than fancier alternatives |

We learned that Black Forest clockmakers in the 18th century were the original backpackers. They'd strap dozens of clocks to their backs and walk as far as Russia to sell them. Talk about a heavy load! These clock-peddlars would trek through snow and over mountains, which makes our travel with a single backpack seem like a walk in the park.

|

|

Traditional cuckoo clocks displayed in the Hornberg workshop Early models used goat bladder bellows because it was cheaper than leather and readily available from local farms |

Long before Henry Ford, Black Forest clockmakers had their own assembly line. Each clock was made by a team of specialists: one carved the case, another made the gears, a third painted the dial and a fourth installed the cuckoo. This division of labor meant they could produce clocks faster and cheaper, which is why every tourist could afford one (or three).

|

|

Ornate Black Forest clocks featuring scenes the region's artisans know tourists will buy Modern workshops use CNC machines for rough carving then claim it's all done by hand because tradition sells |

During World War II, the Black Forest clockmakers were drafted into the war effort. Their workshops, once filled with the sound of cuckoos, were retooled to produce parts for bombs and planes. After the war, they returned to making clocks, perhaps with a bit more urgency to enjoy every peaceful moment.

|

|

Detailed view of a traditional Black Forest clock mechanism What began as tax avoidance using untaxed wood became precision engineering that kept better time than metal alternatives |

The cuckoo clock's distinctive sound comes from specially tuned bellows made from goat bladder in early models - a material chosen because it was cheaper than proper leather and readily available from local farms. Modern versions use rubber, which lasts longer but lacks that authentic farmyard heritage.

The House of Black Forest Clocks maintains handcrafting traditions while quietly adopting modern technology. Their "traditional" workshop now includes CNC machines for rough carving, which artisans then finish by hand - a practice they don't advertise because "computer-carved" doesn't sell as well as "centuries-old hand technique."

Schloss Ortenberg: From Medieval Stronghold to Renaissance Real Estate

We passed Ortenberg Castle on our way to Strasbourg, which sits in Baden-Württemberg looking like exactly what you'd expect a German castle to look like. The castle began life in the 11th century as a fortress, which in medieval terms meant "place where people with weapons tell you what to do."

The obscure architectural detail: The castle's transition from fortress to Renaissance palace happened in the 16th century when the owners realized fortifications were becoming less important than showing off wealth. They kept the defensive walls but added fancy windows because nothing says "I'm rich and cultured" like large glass panes that would have been arrow targets in earlier centuries.

|

|

Ortenberg Castle where defensive architecture met Renaissance real estate ambitions The owners kept the walls but added fancy windows when arrows stopped being a daily concern |

If you're looking for a castle stay without the royal budget, Ortenberg Castle has you covered. Since the 1970s, part of the castle has been run as a youth hostel. So you can sleep in a medieval fortress and tell your friends you lived like a king, even if you're sharing a room with ten strangers.

|

|

Ortenberg Castle's courtyard where Renaissance renovations met medieval foundations Creative Commons image by Wolkenkratzer showing what happens when fortress owners get interior design ambitions |

The castle's name comes from Old High German words meaning "mountain place," which shows medieval naming conventions weren't particularly creative. The tower offers views of the Black Forest and Rhine Valley that haven't changed much since the 16th century, except now there are roads and the occasional supermarket.

The castle now hosts concerts and medieval festivals where people dress up in period costumes and pretend life was better before antibiotics and indoor plumbing. Their restaurant serves regional cuisine that's probably more refined than whatever medieval residents ate, though they likely shared similar complaints about tourist prices.

Pont de l'Europe Bridge: Friendship Symbol with Explosive History

As we crossed from Kehl, Germany into Strasbourg, France, we saw the Pont de l'Europe bridge running parallel to our road bridge. This pedestrian bridge symbolizes Franco-German friendship, which is diplomatic speak for "we stopped trying to invade each other every few decades."

The obscure engineering fact: The original 1863 bridge used a novel girder design that allowed it to handle both pedestrian and light rail traffic. When rebuilt in 1960 after WWII destruction, engineers discovered the foundations had survived multiple conflicts because everyone recognized blowing up a Rhine crossing would inconvenience both sides equally.

The bridge hosts the Strasbourg Marathon and Christmas Market, proving that European unity looks better with runners and mulled wine. It's also popular for wedding proposals, though statistics aren't kept on how many couples argue about which country's laws would apply if they got divorced.

Strasbourg, France: Where European Bureaucracy Meets Medieval Charm

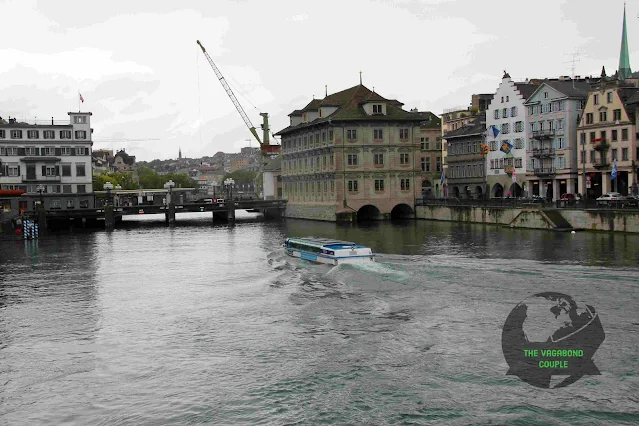

Strasbourg sits in France's Grand Est region looking across the Rhine at Germany and wondering if it should identify more with croissants or bratwurst. The Ill River flows through town alongside canals built over centuries by people who really believed in waterfront property values.

|

|

Strasbourg's skyline as approached from the Rhine River The city that can't decide if it's French or German has made an industry out of European ambiguity |

The city has been ruled by both France and Germany so many times that locals developed a talent for changing flags quickly. Strasbourg now hosts European institutions like the European Parliament, where politicians debate regulations in a building that probably violates several of them.

Strasbourg's historic center Grande Île is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which means it's officially too important to be ruined by modern development, though they make exceptions for souvenir shops selling miniature European Parliament buildings.

|

|

European Union flags at Place de la Gare symbolizing Strasbourg's role as bureaucratic capital The flags represent countries that sometimes agree on regulations after sufficient debate and coffee |

Here's a fun European fact: the European Parliament building in Strasbourg is shaped like a giant wing, but it's a bit of a white elephant. It's only used for four days a month and the rest of the time it sits empty. The building cost over 500 million euros, which is a lot of money for a part-time parliament.

|

|

22 Place de la Gare where Strasbourg's train station meets urban reality The address has seen everything from 19th-century travelers to 21st-century European bureaucrats |

Opéra national du Rhin: Cultural Gem with Acoustic Secrets

The Opéra national du Rhin on Place Broglie opened in 1821 and has been hosting performances for audiences who appreciate culture or just need somewhere to wear their fancy clothes. The building's Neoclassical design by Jean-Nicolas Villot features Ionic columns that say "we take art seriously" in architectural language.

The obscure acoustic detail: The opera house's interior was redesigned in the 1850s using a then-novel horseshoe shape that improved sound distribution. What guides don't mention is that the redesign happened after a visiting Italian tenor complained the original acoustics made him sound "like a duck with sinus problems." The renovation bankrupted the original owner, who then sold the building to the city at a loss.

Inside, gilded stucco work and crystal chandeliers create an atmosphere where even coughing during the performance feels like a cultural transgression. The opera house hosts everything from Mozart to contemporary works that might confuse traditional audiences but make them feel intellectually superior.

|

|

Vertical view of Strasbourg's opera house where architecture meets acoustic engineering The redesign happened after complaints about performers sounding like waterfowl with nasal issues |

Place Broglie: Strasbourg's Square of Shifting Allegiances

Place Broglie is named after Victor-François, 2nd Duke of Broglie, who probably never imagined his name would adorn a square where people now buy overpriced coffee and take tourist photos. The square has seen everything from medieval markets to royal processions to modern-day Europeans trying to find their hotel.

|

|

Rue de la Comédie at Place Broglie where history meets modern tourism The square has hosted everything from medieval commerce to confused travelers with oversized luggage |

|

|