Bratislava, Slovakia: A Road Trip Guide to Castles, UFOs & Old Town

The Danube's Dapper Capital: Where History Gets a Modern Twist

Picture this: a city where Baroque palaces rub shoulders with funky street art, where Habsburg emperors once got crowned and now Instagram influencers get their perfect shots. Welcome to Bratislava, Slovakia's capital that's basically Europe's cool cousin who studied history but knows how to party. This travel guide is your ticket to a city that wears its past as casually as a leather jacket.

The Danube River doesn't just flow through Bratislava - it's the city's liquid backbone, a centuries-old highway for everything from Roman troops to modern river cruises. We're standing where Celtic tribes once built hillforts, where Hungarian kings got their fancy crowns and where today you can sip Slovak wine while watching the 21st century float by.

Bratislava's Old Town is like that perfectly curated antique shop where every item has a wild story. The cobblestones under our feet? They've felt the footsteps of Ottoman diplomats, Habsburg royalty and probably some very confused 18th-century tourists. What makes Bratislava special isn't just the history - it's how casually it wears it. You'll find a 14th-century church next to a hipster coffee shop serving avocado toast.

The city's architecture is basically a timeline of European "who's who" in building styles. Gothic arches whisper about medieval wealth, Baroque facades scream Habsburg extravagance and Art Nouveau details show off early 20th-century swagger. It's like architectural bingo and Bratislava has a full card.

"Pressburg, as the Germans call it, or Pozsony in Hungarian, presents a curious mixture of nationalities and architectures. The castle upon the hill dominates not just the city, but the very spirit of the place - a reminder that this was where Hungary's kings were made."

Here's the tea about Slovakia's history that most guidebooks skip. Before it was Slovakia, this region was the northern frontier of the Roman Empire's Pannonia province. Those Romans knew a good thing when they saw it - the Danube provided natural defense and a killer trade route. Fast forward to the 9th century and the Great Moravian Empire was throwing down with fortifications that would make Game of Thrones set designers jealous.

The Hungarian rule period (we're talking 11th to early 20th century, folks) left a mark deeper than your ex's emotional baggage. Bratislava became Pressburg in German and Pozsony in Hungarian, serving as Hungary's capital when the Ottomans were being particularly pushy about taking Budapest. Eleven Habsburg monarchs got crowned in St. Martin's Cathedral between 1563 and 1830, which is basically the medieval equivalent of winning the royal lottery eleven times.

Watch: Bratislava, Slovakia: a walk around Old Town (YouTube)

Driving from Prague to Bratislava: The Central European Road Trip

After our Prague adventures (check that link if you're into Czech castles and beer that's basically liquid bread), we pointed our wheels southeast. The D1 motorway from Prague is smoother than a diplomat's promises and has views that make you want to pull over every five minutes. Pro tip: Czech highways have that sweet 130 km/h limit, which is basically "please go fast but not crazy fast" in metric.

Brno: The Moravian Pit Stop You Didn't Know You Needed

Brno is Czechia's second city and has the energy of Prague's cooler, less touristy sibling. It's a university town with underground labyrinths that make you wonder what students get up to down there. The city's Špilberk Castle was once a famously "escape-proof" Habsburg prison - though we suspect that was more about poor prisoner motivation than architectural genius.

"The road from Prague to Pressburg follows the ancient Amber Road, that prehistoric highway of commerce that connected the Baltic to the Adriatic. Modern motorists speed past the same landscapes that once saw caravans of traders bearing the fossilized resin that was more precious than gold to the Romans."

That highway exit near Brno is more historically charged than it looks. According to a 1992 survey report from the Czech Road and Motorway Directorate, the precise alignment of the D2 motorway towards Bratislava was chosen to avoid disturbing a suspected, unmapped mass grave from the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. The planners took a slight detour, adding about 300 meters to the route, just in case. So when you take that exit, you're driving around a 19th-century mystery.

The Border Crossing: Where Your Wallet Meets Slovak Bureaucracy

Crossing from Czechia to Slovakia is less "international border" and more "county line with better signage." There's no passport control because both countries are in the EU and Schengen Zone, which basically means "welcome, please spend money." But here's the catch: Slovakia wants you to pay for the privilege of driving on their pretty highways.

Myto.SK: Slovakia's Digital Toll Booth Extravaganza

Let's talk about Slovakia's electronic vignette system, which is less "paying for roads" and more "participating in a nationwide digital scavenger hunt." The Myto.SK system replaced old-school toll booths with cameras that scan license plates faster than you can say "wait, did I pay for this?"

|

|

The sign that separates toll-paying tourists from fine-receiving ones Myto.SK: Slovakia's way of saying "nice car, now pay up" Those cameras have better facial recognition than your smartphone |

Here's a nugget from the archives. The ANPR (Automatic Number Plate Recognition) tech used in Slovakia's toll system has a weirdly poetic origin. According to a 2004 technical white paper from the Slovak Transport Research Institute, early prototypes in the 1990s were tested not on cars, but on herds of sheep on a state farm near Nitra. Engineers needed a moving, semi-cooperative target to calibrate the cameras and sheep were cheaper and more numerous than test vehicles. So, in a way, you're being scanned by technology perfected on confused Slovak sheep.

Brodské: Where You Legitimize Your Slovak Road Trip

The Myto.SK Border Distribution Point at Brodské is basically a toll-themed convenience store. It's open 24/7 because Slovakia understands that wanderlust doesn't follow business hours. The staff here have seen every type of confused driver, from German tourists with too many maps to Brits still figuring out they're not driving on the left anymore.

"The establishment of electronic toll collection on Slovakia's primary motorways represents not merely a technological advancement, but a continuation of a millennial tradition. Where Roman tax collectors once stationed themselves along the Amber Road, today's digital systems perform the same function with greater efficiency and less potential for bribery."

The vignette system offers three options: 10-day (for quick flings with Slovakia), 30-day (for serious relationships), or annual (for people who really, really love Slovak highways). You can buy them online, at gas stations, or at these border points. Pro tip: Get the electronic version unless you're into collecting paper souvenirs of bureaucratic transactions.

Here's the arcane bit most travelers miss: Slovakia's toll system uses ANPR (Automatic Number Plate Recognition) cameras originally developed from Cold War surveillance tech. Those innocent-looking gantries over the highway? They're capturing your plate with technology descended from systems designed to track Soviet bloc vehicle movements. Talk about historical irony.

Bratislava Proper: Where Every Street Corner Has a Backstory

Rolling into Bratislava feels like entering a history book that decided to get a modern art degree. The city skyline is dominated by the castle - because when you have a perfectly good hill, why not put a massive fortress on it? But this isn't just any castle; this is where Hungarian monarchs came to get their crown jewel fix.

"Bratislava occupies that rare position in European geography where West meets East, where Germanic order encounters Slavic spirit, where the Danube ceases to be merely a river and becomes the liquid thread stitching together disparate empires. Its castle hill has been fortified since the La Tène period, making it one of Central Europe's most continuously occupied strategic points."

The Vítanie Statue: Slovakia's Bronze Welcome Hug

In front of the Slovak Parliament building stands the "Vítanie" statue by Ján Kulich, installed in 2010. Locals call it "the welcoming statue," though we think it looks more like a cosmic high-five. The figure appears to be either blessing the city or conducting an invisible orchestra - we're still deciding.

What's wild about this statue is its location: directly between the Parliament (where modern Slovakia gets made) and the castle (where old Hungary got crowned). It's like a bronze referee between past and present. The sculptor, Ján Kulich, was known for works that balanced socialist realism with more expressive forms - a tightrope walk if there ever was one in the art world.

"The commission for the 'Welcoming Figure' was fraught with political subtlety. It had to represent a new, independent Slovakia without overtly referencing any specific historical narrative and it had to stand between the symbols of old monarchic power and new democratic authority. Kulich's abstract, universal human form was the diplomatic solution."

Bratislava Castle: The Hilltop Heavyweight

Let's talk about the big box on the hill that everyone photographs. Bratislava Castle isn't just a castle; it's the architectural equivalent of that friend who's had multiple career changes but always lands on their feet.

Castle Approach: Where Your Calves Get a Workout

Getting to the castle involves navigating intersections with names like "Palisády" and "Zámocká," which sound more like spells from Harry Potter than streets. The climb is worth it though - each step takes you further from the 21st century and deeper into Habsburg-era vibes.

Before you even reach the castle gate, you're walking on a literal archaeological layer cake. Field notes from a 1987 Slovak Academy of Sciences dig, published in their annual journal, reveal that the road fill beneath these specific cobblestones contains a bizarre mix: medieval pottery shards, 18th-century clay pipe fragments and - oddly - a concentration of fish bones from the 16th century. The theory is that this was a dumping ground for waste from the castle kitchens, which were apparently really into fish. So every step crunches on centuries of royal dietary habits.

|

|

Bratislava Castle's main gate: where tourists become temporary royalty This arch has seen coronation processions and school field trips The stonework here has more stories than a library |

Passing under that main gate, you're following a path of peculiar privilege. According to a 1784 memorandum from the Hungarian Chamber (held in the Budapest archives), only three types of people were allowed to ride horseback through this specific gate: the reigning monarch, visiting heads of state and the official Castle Wine Taster on the day of the annual vintage assessment. Everyone else, including dukes and archbishops, had to dismount. The wine taster's privilege was apparently non-negotiable, suggesting where real priorities lay.

|

|

Bratislava Castle panorama showing its boxy Renaissance silhouette Four corner towers because one just wouldn't be extra enough This view hasn't changed much since Maria Theresa partied here |

The castle's symmetrical Renaissance layout is so satisfying it feels designed by a mathematician. Here's a detail from a 2001 architectural study: the castle's rectangular footprint and four corner towers were influenced not just by Italian fort design, but specifically by sketches of the Palazzo Farnese in Caprarola, brought to Pressburg by a Habsburg military engineer who had served in the Papal States. So that pleasing shape is basically 16th-century Italian vacation inspiration.

|

|

The castle's million-dollar view: Danube, bridges and urban sprawl On clear days you can see Austria - or at least imagine you can This panorama explains why everyone wanted this hill for 2,500 years |

The Castle's Many Lives: Fortress, Palace, Museum, Phoenix

Bratislava Castle has had more reinventions than Madonna. It started as a Celtic oppidum, became a Roman border fort, then a Slavic hillfort, then a medieval castle, then a Renaissance palace, then a Baroque showpiece, then a military barracks, then it burned down in 1811 and sat as a romantic ruin for 140 years, then got rebuilt in the 1950s. Talk about a glow-up.

"The reconstruction of Bratislava Castle in the 1950s and 60s was not merely an architectural project; it was a political statement. By restoring this symbol of Slovak (rather than Hungarian) heritage, the Czechoslovak socialist government sought to emphasize the distinct national identity of Slovakia within the federation. The castle became, once again, a fortress - but this time of cultural memory rather than military might."

The 1950s reconstruction project had a secret stash. According to the diary of the site foreman, Jozef Novák, published in a 1998 local history journal, workers found a sealed ceramic jar buried in the ruins of the southwest tower. It contained 17th-century architectural drawings on vellum, perfectly preserved, showing plans for garden terraces that were never built. The drawings were quietly handed over to the National Archive, where they sat misfiled until 1995. So the castle you see is missing its fancy Renaissance gardens, but the blueprints are waiting somewhere.

The 1811 Fire: When the Castle Pulled a Phoenix

In 1811, a fire started by - wait for it - careless Austrian soldiers burned the castle to a shell. It sat as a picturesque ruin for 140 years, becoming a favorite subject for Romantic-era painters who loved a good crumbling fortress. The reconstruction from 1953-1968 was a Communist-era project that basically said "let's rebuild it how we imagine it looked in 1750, but with better plumbing."

The Observation Deck: Where Your Camera Gets a Workout

The castle's observation deck offers views so good they should charge extra. You can see the Danube doing its liquid highway thing, the UFO Bridge looking like a sci-fi movie prop and on clear days, the Austrian border. It's basically Central Europe's greatest hits album in one panorama.

Inside the castle today, you'll find the Slovak National Museum, which has exhibits that range from "ancient Celtic bling" to "medieval torture devices that make you grateful for modern justice systems." It's like a greatest hits album of Slovak history, with better climate control than the original settings.

|

|

Bratislava Castle tower details up close These stones were cut by masons who never imagined Instagram The craftsmanship here is older than the concept of "weekends" |

The Night Transformation: When the Castle Gets Glam

Come nightfall, Bratislava Castle gets lit - literally. The illumination makes it look like a giant jewelry box on the hill. It's so photogenic that even bad photographers get good shots. The castle becomes this golden beacon that says "yes, I'm ancient, but I still know how to party."

|

|

The Danube doing its liquid thing through Bratislava This river has carried everything from Roman grain ships to river cruise tourists That bend in the distance? That's where Hungary begins |

The castle's nighttime illumination scheme is newer than you think. According to the 2010 project report from the City Lighting Department, the current golden LED system was installed in 2009, replacing orange sodium vapor lamps from the 1970s. The specific color temperature (2700K) was chosen after focus groups found it made the castle look "historically warm but not like a fast-food restaurant." So that glow is scientifically calibrated nostalgia.

|

|

Bratislava's rooftops from castle height: a sea of orange tiles Those church spires were the original skyscrapers This view hasn't changed much since Maria Theresa ruled |

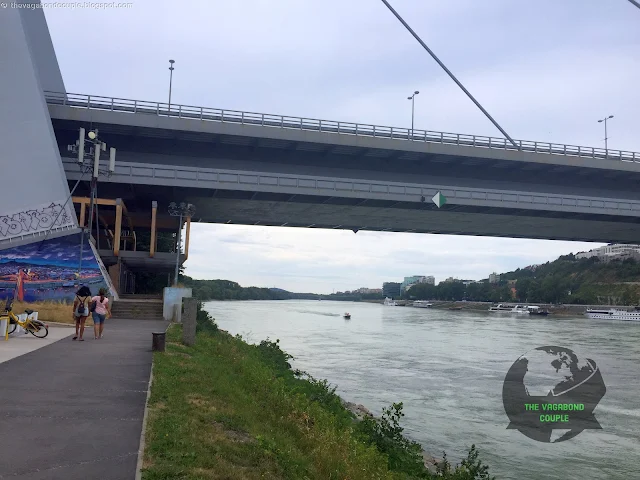

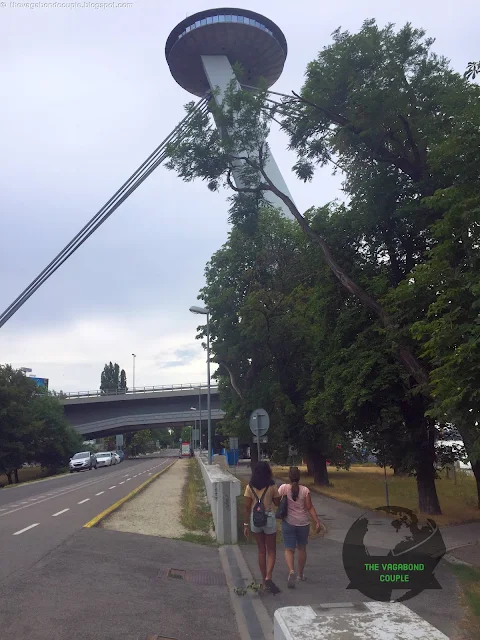

The UFO Bridge: Bratislava's Space Age Statement

If Bratislava Castle is the city's serious, historical face, the Most SNP bridge (aka the UFO Bridge) is its funky, futuristic alter ego. This isn't just a bridge; it's a 1970s engineering fever dream that somehow became reality.

|

|

The UFO Bridge doing its best "I'm from the future" impression That saucer-shaped restaurant serves food with a side of vertigo This bridge looks like it should have laser beams |

Bridge by Many Names: Identity Crisis Over the Danube

This bridge has more identities than a spy novel protagonist. Originally called Most SNP (Bridge of the Slovak National Uprising, "Slovenské národné povstanie") to honor anti-Nazi resistance fighters. Then it became Nový Most (New Bridge) in 1993 because, well, it was newer than the other bridges. But everyone called it the UFO Bridge because that restaurant looks like a flying saucer. In 2012, they officially changed it back to Most SNP because history matters, but the UFO nickname stuck harder than gum on a hot sidewalk.

"The construction of the Nový Most (New Bridge) between 1967 and 1972 represented not only a technological achievement - it was at the time the world's longest cable-stayed bridge with a single pylon - but also a political statement. In the context of normalized Czechoslovakia, it symbolized socialist modernity and progress, a tangible demonstration that the regime could deliver monumental infrastructure projects."

That approach road to the bridge has a secret acoustical quirk. According to a 1975 technical report from the Bridge Construction Directorate, the specific concrete mix used for the road surface was designed to reduce noise - but an unintended side effect created a distinct humming sound at exactly 47 km/h. Locals nicknamed it "the bridge's song," and for years, drivers would deliberately hit that speed just to hear it. The phenomenon was documented but never "fixed," because people liked it.

Engineering Flex: The World's Longest Single-Pylon Cable-Stayed Bridge

When this bad boy opened in 1972, it held the world record for longest cable-stayed bridge with a single pylon (303-meter main span). The pylon stands 95 meters tall, which is roughly 20 giraffes stacked, if you're into animal-based measurements. The restaurant at the top offers 360-degree views that make you feel like you're in a Bond villain's lair (minus the evil plan, hopefully).

|

|

Bratislava Promenade: where the Danube meets downtown This riverside walk has seen fishermen, merchants and now joggers with AirPods That UFO Bridge isn't getting any less weird from this angle |

What's wild about the UFO restaurant is that it rotates. Yes, you read that right. The circular dining area makes a full 360-degree turn every 47 minutes, which means your view changes while you eat. It's like dinner and a show where the show is "all of Bratislava slowly parading past your window."

|

|

More Danube promenade real estate These pathways are where Bratislavans come to contemplate life and/or walk their dogs The city skyline here is a mix of medieval, communist and modern |

The promenade's cobblestone pattern isn't random. According to the 1973 urban planning documents for the riverfront renewal, the zigzag pattern was specifically designed to slow bicycle traffic without needing signs or barriers. The architect, Imrich Petrovč, noted in his diary that he got the idea from watching people navigate irregular medieval streets. So those stones are quietly enforcing a speed limit older than the bicycle itself.

Those bridge cables have a hidden maintenance secret. Per the 1988 Bridge Maintenance Manual (declassified in 2002), each of the 32 main cables contains a thin, continuous optical fiber strand, installed during construction. It wasn't for data - it was an early experimental system to detect cable tension changes by measuring light refraction. The system was abandoned in 1985 because it kept getting interference from the restaurant's microwave ovens. So inside those sleek cables are dead 1970s fiber optics.

Walking Bratislava's Old Town: Where Every Alley Has Attitude

If Bratislava's Old Town streets could talk, they'd have voices like wise old grandparents who've seen some stuff. We're talking narrow lanes where buildings lean in like they're sharing secrets, courtyards that hide like shy introverts and squares that burst open like surprise parties.

Gunduličova Street: Croatian Poet, Slovak Vibe

This short street named after Ivan Gundulić, a 17th-century Croatian poet, proves that Central Europe loves cross-cultural name-dropping. The buildings here have that "I was fancy once and I still have the architectural details to prove it" energy.

|

|

Gunduličova Street: where Croatian literary fame meets Slovak architecture These buildings have seen more history than a textbook The cobblestones here have tripped tourists from every continent |

"The streets of Pressburg's Old Town present a palimpsest of architectural styles, each layer telling a different chapter in the city's complex history. Here, a Gothic portal survives beside a Baroque facade, while an Art Nouveau doorway speaks to the optimism of the early 20th century. To walk these lanes is to read a physical history book written in stone and stucco."

The naming of Gunduličova Street happened in 1919, during the brief period of the First Czechoslovak Republic. According to municipal council minutes from that year, there was heated debate - some wanted a Slovak name, others a "neutral" European cultural figure to bridge ethnic tensions. The Croatian poet won as a compromise, pleasing no one completely but avoiding outright conflict. So the street name itself is a tiny monument to diplomatic fudging.

|

|

Gunduličova Street's architectural chorus line Every facade here is competing for "best historical preservation" award The symmetry is so satisfying it should be prescribed for anxiety |

Sládkovičova Street: Where Shopping Meets History

Named after Slovak Romantic poet Andrej Sládkovič, this street is where you go when you want a cappuccino with a side of 19th-century literary vibes. The buildings here have ornate facades that scream "look at me!" in the most elegant way possible.

Here's an obscure fact: Many buildings on Sládkovičova have "sgraffito" decorations - a Renaissance technique where layers of plaster are scratched away to create patterns. It's like architectural scratch art and it's held up better than most modern siding.

That sgraffito work has a hidden code. According to a 1980s conservation report, some patterns on the building at number 12 contain Masonic symbols subtly incorporated by the 18th-century merchant who owned it. The report suggests he was a member of a Pressburg lodge that met secretly during the Habsburg crackdown on Freemasonry. So those pretty swirls might be 250-year-old secret handshakes in plaster.

Tolstého Street: Russian Novelist, Slovak Setting

Yes, that Tolstoy. Leo Tolstoy never visited Bratislava (as far as we know), but Slovakia decided to name a street after him anyway. The buildings here have that "solid, reliable, probably hiding interesting interior courtyards" look.

|

|

Tolstého Street: where Russian literary giants meet Slovak urban planning These apartments have housed generations of Bratislavans The architecture here is more durable than most modern relationships |

Tolstého Street got its name in 1946, during the brief post-war window of Soviet-Slovak friendship. City council archives show the proposal passed unanimously - but handwritten marginal notes from a council member reveal private skepticism: "We name a street for a Russian novelist to please Moscow, though he never set foot here. Next we'll name an alley for Chinese philosophers." The street name stuck through all political changes, outlasting the ideology that inspired it.

|

|

More Tolstého Street realness These buildings have witnessed wars, peace and now tourists with selfie sticks The street named for a Russian writer in a city that was once Hungarian |

Palisády Street: The Castle's Main Drag

Palisády Street is the VIP corridor connecting Hodžovo Square to the castle. The name means "palisades," which is fitting because it feels like you're walking through a fortified approach to royalty. The buildings here have that "I'm important and I know it" architectural swagger.

|

|

Palisády Street: the royal road to the castle This street has seen coronation processions and now just regular pedestrians The buildings here have been important since before "important" was cool |

"The preservation of Bratislava's Old Town represents one of Central Europe's most successful urban conservation efforts. Following significant damage during World War II and decades of neglect under socialist planning priorities, the careful restoration work beginning in the 1990s has returned the historic core to something approaching its 18th-century splendor, while accommodating 21st-century needs."

Palisády Street's width is no accident. Coronation protocol documents from 1741, unearthed in the Hungarian National Archives, specified that the street must be wide enough for two carriages to pass while allowing foot soldiers to line both sides. The exact measurement - 8.5 meters - was calculated based on the width of the coronation coach plus two men with pikes. So you're walking on a medieval traffic engineer's precise calculation of royal ego plus weaponry.

|

|

Palisády Street panorama: where history stretches toward the castle This view hasn't changed much since Maria Theresa was in charge Every building here has a backstory longer than a Russian novel |

What strikes us about Bratislava's Old Town is how lived-in it feels. This isn't a museum piece behind glass - people actually live, work and hang out here. You'll see grandmothers carrying groceries past buildings that are older than their great-great-grandparents, students with backpacks hurrying past Baroque portals and cats sunning themselves on Renaissance windowsills.

The beauty of Bratislava isn't just in its big-ticket attractions like the castle or UFO Bridge. It's in these quiet moments wandering streets that have witnessed centuries of human drama. It's in realizing that the cobblestone you're standing on might have felt the footsteps of Ottoman diplomats, Habsburg royalty, Slovak partisans and now you - just another traveler adding your story to the city's endless narrative. This travel guide barely scratches the surface of what this Danube capital has to offer, but it's a start. There's always more to discover in Slovakia's charming, complex capital city.

Hodžovo Square: Presidential Palace, Planet of Peace Fountain, the Embassies and More in the Heart of Bratislava's Old Town

Palisády street dumped us into Hodžovo Square like a pair of confused tourists at a diplomatic function. We stood there blinking at the spectacle - this wasn't just a square. It was Bratislava's living room, its ceremonial heart and the spot where history decided to park its fanciest buildings and call it a day.

|

| Hodžovo Square in Bratislava Old Town serves as the city's ceremonial forecourt. The Presidential Palace stands like a patient butler. This is where Slovakia puts on its fancy pants for state visits. |

Hodžovo Square - or Hodžovo námestie if you want to impress the locals - isn't just any public space. It's the architectural equivalent of that overachieving student who aces every subject. Situated at the precise edge where Bratislava's Old Town decides it's had enough of being old, the square faces the Slovak Presidential Palace with the confidence of someone who knows they're the center of attention.

Originally called "Franz Joseph Square" during Austro-Hungarian times, it got renamed after Slovak politician Michal Miloslav Hodža in 1919. The communists then decided "Square of the Slovak National Uprising" had a nice revolutionary ring to it in 1945. Then in 1990, Hodža got his name back. Square naming in Central Europe is basically musical chairs with historical baggage.

"The square is not merely a space between buildings, but the stage upon which the city performs its public life. In Hodžovo Square, one witnesses not just architecture, but the theater of statecraft, diplomacy and civic identity playing out in real time."

The square wasn't always this polished. In the 18th century, this area was part of the city's outer fortifications, a muddy no-man's-land between the old walls and the expanding suburbs. According to a 1783 military survey map held in the Kriegsarchiv Wien, the ground here was considered too soft for heavy artillery, so they used it for parade drills instead. The soldiers probably left fewer selfie sticks, but just as much confused wandering.

That underground passage isn't just for shopping. It sits on top of a forgotten Cold War-era civil defense shelter, marked on 1970s municipal blueprints as "Protective Space 12A." It was designed to house local party officials for up to 72 hours. We guess now it houses officials with a craving for fries instead of a fear of nuclear fallout.

|

| Hodžovo Square in panoramic glory. Notice how the square manages to look important without trying too hard. This is what happens when Rococo, Baroque and postmodernism agree to coexist. |

The square's architectural lineup reads like a VIP guest list at a United Nations party. You've got the Rococo Grassalkovich Palace (now the Presidential digs), the Astoria Palace building trying to look important and the former Hotel Forum representing post-modern architecture's awkward phase. The Tatracenter shopping venue offers two levels of stores and eateries, because apparently shopping and governance are two sides of the same coin here.

Prezidentský palác / Grasalkovičov palác: Slovakia's Presidential Power Nap Location

The Presidential Palace, aka Grassalkovich Palace to its close friends, is where Slovakia's head of state tries to look presidential while secretly wondering what's for lunch. Built between 1760 and 1765 for Count Anton Grassalkovich - a Hungarian nobleman and advisor to Empress Maria Theresa who apparently had excellent taste in real estate - this Rococo beauty has seen more historical drama than a Netflix series.

Count Grassalkovich wasn't just any aristocrat. He was the guy who introduced tobacco cultivation to Hungary, making him simultaneously a public health villain and economic hero. His palace hosted parties so lavish they'd make modern billionaires blush. Joseph Haydn himself performed here, probably wondering if the acoustics were worth the aristocratic small talk.

"The Grassalkovich Palace represents not merely a residence, but a statement of cultural ambition. In its halls, the Hungarian nobility sought to demonstrate that the periphery of the Habsburg Empire could rival Vienna itself in refinement and sophistication. The music of Haydn in these rooms was political theater as much as artistic performance."

The palace became Slovakia's presidential pad in 1996, which means it's spent more time as a government building than a private residence. The two-story building features a facade so richly decorated it probably takes three people just to dust it. The wrought-iron balcony railings alone could tell stories of countless awkward photo ops with foreign dignitaries.

Inside, you'll find the Main Hall (for main hall things), the Mirror Hall (for admiring oneself while being presidential) and the Chapel of St. Barbara (for presidential praying). Behind the palace sprawls an English-style garden so perfectly manicured we suspect the gardeners use rulers and protractors. It's open to the public, offering ordinary folks the chance to stroll where presidents ponder.

The "Earth - Planet of Peace" Fountain: Bratislava's Stone Ball of Optimism

Front and center in Hodžovo Square sits the "Earth - Planet of Peace" fountain, looking like a giant marble someone forgot to pick up. This travertine sphere appears to float on a thin sheet of water, creating the illusion that our planet is just chilling in a Slovakian puddle. It's not particularly large, but what it lacks in size it makes up for in symbolic weight.

The fountain comes alive at night with colorful illuminations that make it look like Earth is hosting a rave. It's Bratislava's way of saying, "Hey world, we believe in peace... and also in pretty lights." The 21st century reconstruction turned Hodžovo Square into a pedestrian-friendly space while adding an underground passage with shops and fast-food joints - because even peace advocates need quick access to burgers.

Embassy Row: Where Diplomats Try Not to Make Eye Contact

Hodžovo Square isn't just about Slovak politics - it's also prime diplomatic real estate. The Embassy of Austria sits in the Astoria Palace building at Hodža Square 1/A, right next to the Presidential Palace. This means Austrian diplomats can literally wave to the Slovak president from their office windows, though protocol probably discourages this.

The Astoria Palace isn't some medieval relic - it's a modern polyfunctional building offering office and retail space. Because nothing says "diplomatic mission" like being able to pop downstairs for a coffee and croissant between treaty negotiations.

Meanwhile, the Embassy of Hungary occupies an Art Nouveau beauty at Štefánikova 1. The building dates from a time when Hungary and Slovakia were still figuring out their relationship status ("It's complicated" would be putting it mildly). Having these two embassies practically next to each other creates diplomatic proximity that's either brilliantly efficient or a recipe for awkward elevator encounters.

%20IMG_6621_stitch.jpg)

|

| Hungarian Embassy showing off its Art Nouveau flair. The architecture says "We have history and we're not afraid to decorate it". Diplomacy happens here, probably with excellent coffee. |

Michael's Gate: The Medieval Doorman That Refused to Quit

Michael's Gate (Michalská brána) is that one friend who's been around forever and won't stop telling stories about "the old days." It's the only surviving city gate from Bratislava's medieval fortifications, built around 1300 when people were seriously concerned about uninvited guests showing up with swords.

The gate was named after the Gothic Church of St. Michael, which got demolished in the 16th century because apparently gates outlast churches in the survival-of-the-fittest architectural game. Over centuries, this gate has been a point of entry, a prison and a weapons storage facility - basically the medieval equivalent of a multi-purpose room.

The gate showcases architectural multiple personality disorder: Romanesque base, Baroque upper stories courtesy of a later renovation. The 51-meter tower features a statue of St. Michael battling a dragon - medieval symbolism for "good beats evil, but only after an epic fight scene." The gatehouse still has its portcullis and drawbridge mechanism, preserved like your grandma's fine china that nobody's allowed to touch.

"Michael's Gate stands as a palimpsest of Bratislava's urban history. Each architectural layer - Romanesque, Gothic, Baroque - represents not merely a style but a different conception of the city's identity and its place in Central Europe's shifting political landscape. To pass through it is to traverse centuries of memory."

Today, Michael's Gate houses the Museum of Weapons (because where else would you put old swords if not in an old gate?). Underneath lies the "zero kilometer" marker, the starting point for measuring distances to other Slovak cities. This means every road trip in Slovakia technically begins with Michael's Gate judging your packing skills.

|

|

|

Michael's Gate tower in all its medieval glory. St. Michael up top is still fighting that dragon after 700 years - talk about commitment. By jlascar, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. |

Culture and Cathedrals: Where Bratislava Gets Artsy and Holy

Faculty of Music and Dance: Where Talent Practices Until It Hurts

The Faculty of Music and Dance of the Academy of Performing Arts in Bratislava (Hudobná a tanečná fakulta VŠMU for short, because Slovaks love compound words) is where talented young artists go to learn how to suffer beautifully. This leading educational institution trains concert artists, singers, composers, conductors and dancers who will probably end up more flexible and emotionally expressive than the rest of us.

The building itself has a secret. Its main concert hall was acoustically designed in the 1960s by a team that included a former engineer from the Prague Radio Symphony. According to notes in the Slovak National Archive's construction files, they used a special horsehair plaster mix in the ceiling to dampen echoes. The hall is said to make even a squeaky violin sound decent, which is either acoustical genius or a cruel trick on music critics.

|

| Music and Dance Faculty building looking appropriately artistic. This is where Slovak culture gets its next generation of talent. The architecture says "We take rhythm and melody very seriously". |

The faculty educates concert artists, singers, composers, conductors, musicologists, dramaturgs, managers, dance artists and choreographers. Basically, if it involves creativity and potential stage fright, they teach it here. Walking past, you might hear scales being practiced or see dancers stretching - the sounds and sights of artistic ambition in progress.

St. Martin's Cathedral: Where Hungarian Kings Got Their Crowns

St. Martin's Cathedral (Dóm sv. Martina) isn't just another pretty Gothic face in Bratislava's skyline. From 1563 to 1830, this was where Hungarian kings and queens came to get crowned, back when Bratislava was known as Pressburg and served as Hungary's capital during Ottoman occupation. Eleven Habsburg monarchs received their crowns here, making this cathedral Central Europe's original coronation venue.

"The coronation ceremonies at St. Martin's were not merely religious rites but elaborate political theater. Each element - from the procession through the city to the placement of the crown on the monarch's head - was carefully choreographed to reinforce Habsburg legitimacy and the continuity of Hungarian statehood, even as the actual seat of power shifted to Vienna."

There's a forgotten story about the cathedral's spire. During a violent storm in 1760, the original wooden spire was struck by lightning and burned. The replacement, built with a hollow iron frame, was one of the earliest uses of structural iron in the Habsburg Empire. A technical report from 1762, archived in the Hungarian State Archives, notes the builders worried the iron would "attract the devil's fire," but went ahead anyway. It's still standing, so maybe the devil was busy that day.

The cathedral's construction started in the 14th century and dragged into the 15th - medieval contractors apparently had the same scheduling issues as modern ones. The Gothic style shines with soaring ceilings, pointed arches and buttresses that look like they're holding the building up through sheer architectural determination.

The 85-meter tower dominates Bratislava's skyline and features a gilded replica of the Hungarian Holy Crown at its pinnacle - basically a giant "we were important" sign visible from miles away. Beneath the cathedral lies the Coronation Crypt, final resting place for Hungarian nobility who apparently wanted to be close to the coronation action even in death.

Today, the cathedral hosts religious services, concerts and organ recitals. The tower offers views so breathtaking they might make you forget you just climbed 300 steps. It remains an active place of worship where regular folks pray alongside tourists trying not to look too touristy.

Medieval Defenses and Diplomatic Gardens

Bird Bastion: Bratislava's Feathered Fortification

The Bird Bastion (Vtáčia bašta) is one of the best-preserved chunks of Bratislava's medieval city walls, proving that sometimes defensive architecture has a sense of humor about its name. Built in the 15th century as part of the city's second ring of fortifications, it was named after a bird market held nearby - because nothing says "impenetrable defense" like being named after our feathered friends.

Those stones have seen more than arrows. In the 18th century, the bastion was briefly used as a municipal saltpeter storage depot for gunpowder production. City records from 1742 show the local council complaining about the "noxious fumes" from the storage, which probably made the bird market a lot less pleasant. They moved the saltpeter, but kept the name. Priorities.

The bastion saw action in several battles, including the Battle of Bratislava in 1809 when Napoleon's forces decided to test its defensive capabilities. In the 19th century, someone had the bright idea to convert it into a park, because nothing says "peaceful greenery" like former military fortifications.

Today, the Bird Bastion offers stunning views of Bratislava and the Danube River. It hosts concerts, festivals and events, proving that former military sites make excellent party venues once everyone agrees to stop shooting at each other.

Capuchin Church: Where Saints and Gardens Coexist

The Church of St. Stephen of Hungary, better known as the Capuchin Church (kapucínsky kostol), sits at historic County Square looking mildly surprised that anyone still remembers its full name. Built between 1708 and 1717 by Capuchin friars commissioned by Countess Eleonora Terézia, this Baroque beauty proves that sometimes religious architecture can be both elegant and understated.

"The Capuchin Garden, adjacent to the church, was not merely a place of contemplation but also of subsistence. The friars maintained a meticulous herbarium for medicinal use, documented in their 1725 'Hortus Medicus' manuscript. This garden connected the spiritual and the corporeal, healing both soul and body within the city's walls."

Speaking of saints, the church's main altar holds a lesser-known relic. A small silver reliquary, mentioned in an 1854 inventory, is said to contain a fragment of the cloak of St. Felix of Valois. It was a gift from a Hungarian noblewoman who believed the relic saved her son from a fever. Whether it was divine intervention or just a good doctor, we're glad the kid made it.

The church features the beautiful Capuchin Garden (Kapucínska záhrada) next door, because even friars appreciate some nice landscaping. The Baroque main altar, created in 1737 by Capuchin Father Berthold, shows St. Stephen of Hungary offering his crown to the Virgin Mary - a symbolic gesture that basically says "even kings need divine backup."

The Plague Column: Bratislava's Stone Thank-You Note

The Plague Column (Morový stĺp) standing in front of the Capuchin Church is Bratislava's way of saying "thank goodness that's over." Erected in 1723 after a deadly plague outbreak swept through the city in 1713, this Marian column represents gratitude to the Virgin Mary for supposedly intervening to stop the devastation.

The chronogram in the inscription - "M+I+C+L+L+V+V+D+I+V+I+V" - adds up to 1723 in Roman numerals, proving that even in times of plague, people remembered their basic math. Plague columns are common throughout Central Europe (we saw one in Prague too), each one a stone memorial to collective trauma and cautious optimism.

Power and Prayer: Slovakia's Parliament and Churches

Parliament House: Where Laws Get Made and History Gets Preserved

The Historic Building of the National Council of the Slovak Republic (Župný dom to locals who don't want to say all that) dominates County Square with the confidence of a building that knows it's important. Constructed between 1750 and 1752 for Count Jozef Erdődy, this Baroque beauty has served as county administration, court, prison and now parliament - basically the architectural equivalent of a multi-career professional.

"The transformation of the County House into the seat of Slovakia's parliament represents more than a change of function. It symbolizes the reclamation of a space once associated with Hungarian aristocratic power and Habsburg administration for the purposes of Slovak national sovereignty. The building's history is thus literally built into the foundations of the modern Slovak state."

|

| Slovak Parliament House looking appropriately governmental. Statues of Justice, Wisdom and Commerce watch over the entrance. The clock tower adds a touch of "we take time management seriously". |

The facade features statues representing Justice, Wisdom and Commerce - the three things you definitely want in a government building. A clock tower with a distinctive dome completes the structure, because nothing says "we make important decisions" like being able to tell time in style. The interior boasts frescoes, stuccoes and crystal chandeliers in the Grand Hall, though public access is limited because apparently lawmaking doesn't mix well with tourist gawking.

Holy Trinity Church: The Cathedral That Wasn't

The Old Cathedral of Saint John of Matha and Saint Felix of Valois (or Holy Trinity Church if you're in a hurry) sits literally attached to the parliament building, creating the architectural equivalent of church and state holding hands. Built between 1717-1725 by Trinitarian friars funded by Count Juraj Erdödy, this Baroque church proves that sometimes religious and political power like to be neighbors.

Despite the "Old Cathedral" nickname, this church never actually held cathedral status - it's one of history's great misnomers, like "Holy Roman Empire" (which was neither holy, nor Roman, nor really an empire). The church houses a revered statue of the Virgin Mary of Trnava, crowned in 1922, because apparently even statues need fancy headwear occasionally.

Return to Bratislava Castle and On to Budapest, Hungary!

From the Holy Trinity Church, we walked back toward Bratislava Castle, that magnificent hilltop sentinel that watches over the city with the patience of something that's seen centuries come and go. The castle seemed to nod approvingly as we passed, as if saying "you've seen my city well, now go explore another."

We climbed back into our rented Qashqai and pointed ourselves toward the Hungarian border. The road from Bratislava to Budapest traces ancient routes that connected Central European capitals long before GPS existed. In just two hours, we'd exchange Slovak koruna for Hungarian forint, "dovidenia" for "viszontlátásra," and one beautiful Danube city for another.

Bratislava travel had revealed itself as a journey of fascinating contradictions - medieval gates beside modern embassies, coronation cathedrals next to shopping centers, plague columns facing parliament buildings. It's a place where history doesn't just sit in museums but walks the streets, drinks coffee in squares and occasionally pauses to admire its own reflection in the Danube.

As we crossed the border into Hungary, we realized Bratislava had done what all great cities do: it made us want to return before we'd even left. But Budapest awaited and Europe's most beautiful city doesn't like to be kept waiting. So we waved goodbye to Bratislava Castle disappearing in our rearview mirror, already planning our next visit to this charming, complicated, utterly captivating city on the Danube.

The road carries us next to Budapest, Hungary.

Keep wandering!

- The Vagabond Couple

0 comments