Fes El-Bali: We did not get fazed by the epic maze of Medina of Fez | Morocco, Africa

|

| Khrachfiyine Pont on Bou Khrareb river, Medina of Fez |

After an epic sunrise camel ride back from our desert camp on Erg Chebbi dunes at Merzouga (see The Great Sahara of Morocco) and an unforgettable road trip from Merzouga to Fes over High and Middle Atlas mountain ranges and river valleys (see Merzouga to Fes Desert Road over High & Middle Atlas Mountain Ranges), we reach the ancient walled medina of Fez, the legendary Fes el Bali, at 5 PM. I gotta say, after all that desert heat, the idea of a medieval city with actual shade sounded like paradise.

The entire medina of the ancient 9th century city of Fes is a UNESCO world heritage site for good reason. "Founded in the 9th century, Fez reached its height in the 13th-14th centuries under the Marinids, when it replaced Marrakesh as the capital of the kingdom. The urban fabric and the principal monuments in the medina - madrasas, fondouks, palaces, residences, mosques and fountains - date from this period. Although the political capital of Morocco was transferred to Rabat in 1912, Fez has retained its status as the country's cultural and spiritual centre", say UNESCO.

Fes el-Bali, a magical 1.15 square miles in area, encloses within its ancient walls over 13,000 historic buildings including 11 theological schools of Islamic studies (madrasas), 320 mosques, 270 dars (B&Bs and hostels) and funduqs (inns and hotels), and over 200 Moorish bathhouses and hammams connected by over 10,000 pedestrian-only streets, a vast majority of which are really narrow 3-foot wide alleys. About 160,000 people live inside Fes el-Bali today. Automobiles are not allowed inside, making it the world's largest car-free medieval city. That's right - the world's biggest pedestrian-only medieval city! Your Fitbit is gonna love it here.

The Neighborhoods of Fes

The city of Fez, Morocco is divided into two main districts or quarters: Fes el-Bali (Old Fes) and Fes el-Jdid (New Fes). Fes el-Bali is the oldest part of Fes and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is a maze of narrow streets and alleyways lined with shops, restaurants, and mosques. Fes el-Bali is also home to several important historical landmarks, such as the University of Al Quaraouiyine, the Bou Inania Madrasa, and the Attarine Madrasa.

Fes el-Jdid is the newer part of Fes and was founded in the 13th century. It is home to the Royal Palace, the Mellah (Jewish quarter), and several other important historical landmarks, such as the Batha Museum and the Bab Bou Jeloud (Blue Gate).

In addition to these two main neighborhoods, Fes is also divided into several smaller neighborhoods, such as Ziat, Batha, R'cif, Bou Jeloud, Nejjarine and Talaa Kbira. These smaller neighborhoods each have their own unique character and attractions. For example, Ziat is known for its traditional Moroccan houses and gardens, while Batha is home to the Batha Museum and the Blue Gate. R'cif is a bustling neighborhood with a large market, while Bou Jeloud is known for its woodworkers and metalworkers. Nejjarine is a traditional neighborhood with a leather tannery and a copper market, while Talaa Kbira is a major shopping street.

Here is a map of incredible rues, derbs and alleys we walked to explore the medina of Fes and its unforgettable monuments and shrines of Fes el-Bali (link to full map).

Welcome to Fes el Bali

July 15, 2023

|

| Cart Rental service at the entrance to Fes el-Bali - your first introduction to medieval logistics |

Only pedestrians and two-wheelers are allowed in the maze of narrow alleys of Fes el-Bali. Our driver from Merzouga drops us off next to Batha Fountain at Cinema Cafe on Rue Sidi El Khayat just outside the wall of the medina. We have to walk to our riad (B&B / hotel, house with central courtyard and rooms around) at the center of the old medina from here. This is where you realize your luggage has been training for this moment its entire life - but wait, there's a solution!

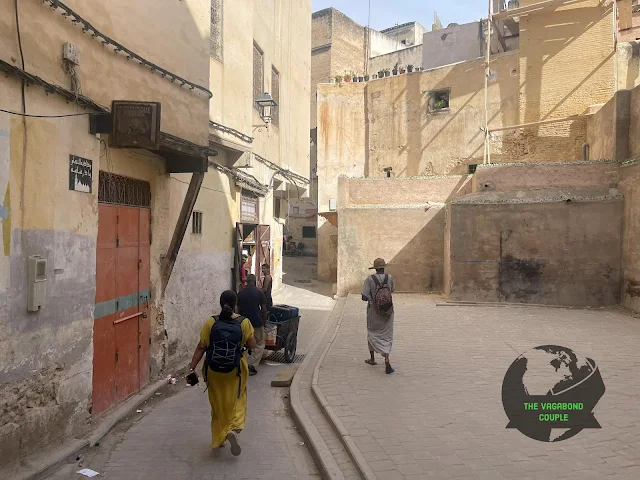

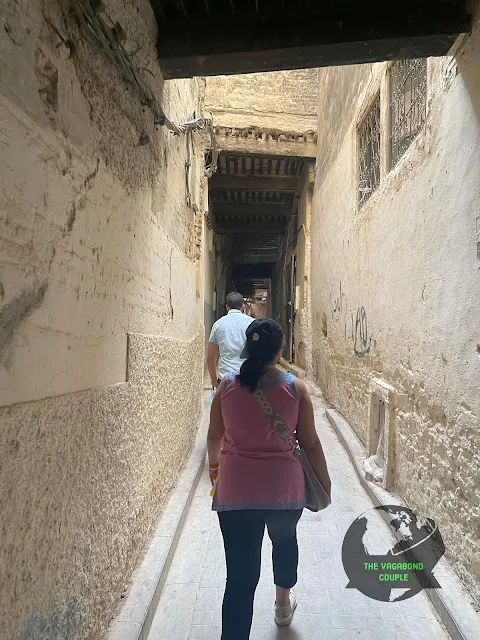

Traversing alleys to our riad (dar) in Fes el-Bali - note the cart barely fits!

Fortunately there are people here who load luggage onto little two-wheeled carts which they manually push to whatever riads, dars or funduqs tourists are heading to. The person and the cart are both collectively called "cart" one of which we hire to take us and our luggage to our riad that is at the center of walled old town. It's like medieval Uber, but with more sweat and better calves.

Our cart guide knows alleys even Google Maps hasn't discovered yet

The cart service of Fes el-Bali immediately elevates our comfort level above that in Marrakech where we had to haul our own luggage over sprawling Jemaa el-Fna in desert heat and were scammed into paying for directions (see Marrakech: Daughter of the Desert and Atlas Mountains). Here, you pay a few dollars and someone else gets the calf workout. It's the little things.

The architectural details you notice when you're not struggling with luggage

The cart service costs U$ 3 going in because it is mostly downhill to the old city. As we will find out later, a trip back out is a more laborious uphill journey costing US$ 5. It's basically medieval surge pricing based on gravity.

Some alleys are so narrow you could high-five your neighbor through the windows

Another great advantage of renting a cart is we do not have to figure out how to get to our riad in the maze of alleys. Let's be real: without a guide, you'd probably end up at someone's grandmother's house asking for mint tea within 10 minutes. The medina is that confusing.

Covered passages provide relief from the Moroccan sun - medieval air conditioning

We follow our cart marvelling at the incredible old city over a good 40-minute walk to our riad. Of course once we reach our riad we have to figure out how we got here to be able to go out and explore the old town with reasonable hope of returning to our beds for the night. Pro tip: take pictures at every turn. Seriously.

The understated elegance of Fes el-Bali residential streets

We have explored ancient alleyways from Greece to Turkey but never ever been in a place like this. The Medina of Fez is on a different level of delightfully confusing chaos, architecture, art and complexity altogether! It's like someone took a dozen ancient cities, threw them in a blender, then poured the result into a maze. In the best possible way.

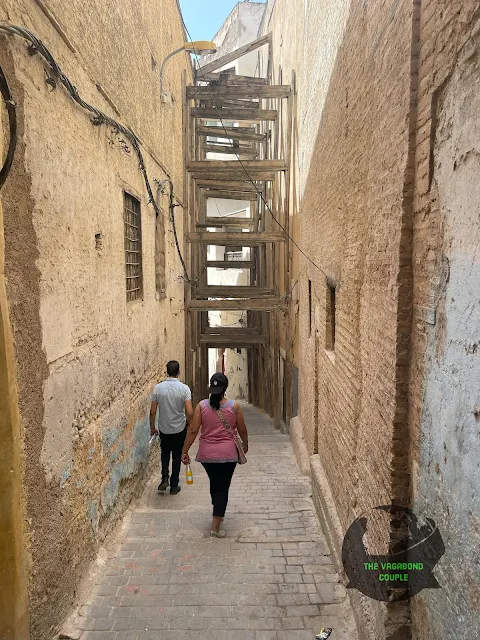

Sloping alleyways that follow the natural topography of the hills around Fez

Our first experience with Fes el-Bali is enhanced by following our cart taking a path down numerous alleys between houses, small squares and intersections that do not exist on Google Maps but ultimately resulting in a shorter walk for those who know their way around here. This is local knowledge you simply cannot get from any app. These shortcuts are passed down through generations, like family recipes but for not getting lost.

The beautiful Moroccan light filtering through ancient alleyways

The geology of Fez is fascinating - the city is built on a series of hills surrounding the Fez River (Oued Fes), which explains all the ups and downs. The original settlement was founded by Idris I in 789 CE on the right bank of the river, and his son Idris II expanded it to the left bank in 809. The river wasn't just decorative - it powered the tanneries and craft workshops that made Fez famous. Today, the river is mostly covered, but its influence on the city's layout remains.

Traditional Moroccan woodwork (zellij) and architectural details

The architecture here follows strict rules based on Islamic principles and local traditions. Houses face inward with courtyards (riads) for privacy, windows on upper floors are often covered with mashrabiya (lattice screens) so women could look out without being seen, and the narrow streets create natural cooling through ventilation. It's medieval climate control at its finest.

Daily life continues unchanged for centuries in these alleys

Fes is famous for its traditional crafts, particularly leatherworking. The tanneries of Fez have been operating since medieval times using methods that are essentially unchanged for a thousand years. They use natural dyes and processing techniques that would make any modern environmentalist proud - if they could get past the smell. More on that when we visit the tanneries!

The endless variety of perspectives in Fes el-Bali's alleyways

One thing you notice immediately is the soundscape. No cars means you hear footsteps, conversations, the call to prayer, merchants calling out, and the occasional donkey. It's a completely different auditory experience from modern cities. You also smell bread baking, spices, occasional whiffs of leather from the tanneries, and mint everywhere.

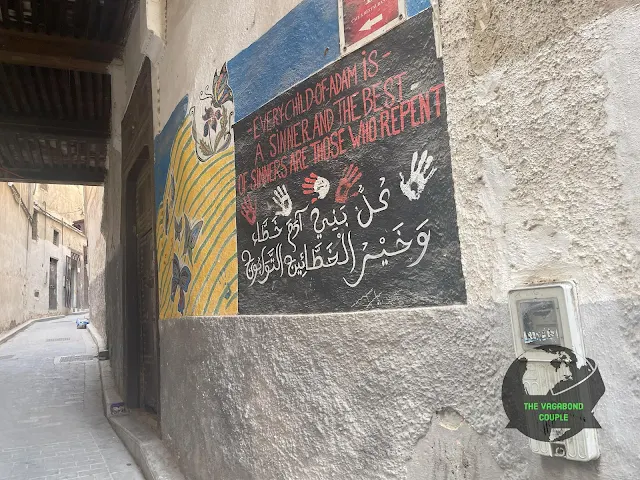

Traditional blue doors believed to ward off evil spirits in Moroccan folklore

In Moroccan folklore, the color blue (like on many doors) is believed to ward off the evil eye. The intricate geometric patterns aren't just decorative either - they represent the infinite nature of God in Islamic art, since only God can create perfection. Humans can only make geometric approximations. Pretty deep for a door, right?

Compact medieval urban planning at its finest in Fes el-Bali

The medina follows what urban planners call "organic growth" - it wasn't planned on a grid but developed naturally over centuries. This creates the maze-like structure but also some ingenious solutions. The narrow streets provide shade, the irregular layout breaks wind, and the density creates community. It's the original walkable city - just don't expect ADA compliance.

The architectural details reveal centuries of craftsmanship

Did you know Fes was once home to the oldest continuously operating university in the world? The University of Al Quaraouiyine was founded in 859 by Fatima al-Fihri, a woman from a wealthy merchant family. It predates both Oxford and Bologna universities. The medina isn't just old - it's historically significant on a global scale.

Life goes on in these medieval streets just as it has for a thousand years

The population density in Fes el-Bali is about 140,000 people per square mile - that's higher than Manhattan! But unlike Manhattan, there are no skyscrapers. The height limit was traditionally about 3-4 stories, which creates that intimate, human-scale feeling. You're always close to people, which can be overwhelming but also creates incredible community bonds.

Islamic geometric patterns that demonstrate mathematical sophistication

The geometric patterns you see everywhere aren't random - they're based on complex mathematical principles developed during the Islamic Golden Age. Moroccan craftsmen used compass and straightedge constructions to create these infinite patterns that seem to repeat forever. It's math made beautiful, and it's everywhere once you start looking.

The rhythm of daily life in Fes el-Bali's ancient streets

Water management was crucial in this semi-arid region. The medina has an elaborate system of fountains (like the one we saw earlier) and underground channels (khettaras) that brought water from the hills. Each neighborhood had its own fountain, and the sound of water was as much a part of the city as the call to prayer.

Some alleys are so narrow they feel like secret passages

The narrowest alleys (some barely 2 feet wide) served multiple purposes: they provided shade, made the city defensible (hard to march an army through), and created microclimates through the venturi effect. The wind gets funneled through, creating natural ventilation. Medieval urban planning was pretty smart!

The famous "sky river" view between closely spaced buildings

Looking up between buildings, you get these beautiful slices of sky that Moroccans poetically call "sky rivers." The buildings are so close together that the sky appears as a narrow blue ribbon overhead. It's a perspective you don't get in modern cities with wide streets.

The harmonious blend of function and beauty in Moroccan architecture

Notice how few straight lines there are? The walls curve, the streets meander, even the doorways aren't perfectly rectangular. This isn't poor craftsmanship - it's intentional. In Islamic architecture, perfection is reserved for God, so human creations should have slight imperfections. It's a humility built into the very walls.

Every turn reveals new architectural wonders in Fes el-Bali

The building materials tell a geological story too. The walls are made of rammed earth (tabout), plaster made from local limestone, and wood from the nearby Middle Atlas mountains. The famous Fes blue in the tiles comes from cobalt, while the greens come from copper. Everything is locally sourced - medieval sustainability!

This isn't a museum - it's a living, breathing medieval city

What's amazing is that this isn't a preserved historic district where people dress up for tourists. This is where 160,000 people actually live, work, raise families, and go about their daily lives. The medina isn't frozen in time - it's evolving while maintaining its essential character. Kids play soccer in alleys that were ancient when Columbus was born.

The play of light and shadow creates ever-changing patterns throughout the day

The light in Fes is famous among photographers. The narrow streets create dramatic contrasts between bright sunlight and deep shadow. The whitewashed walls reflect light into spaces that would otherwise be dark. At different times of day, the same alley looks completely different. It's a photographer's dream and a cartographer's nightmare.

Craftsmanship that has been passed down through generations

The skills to build and maintain these structures aren't taught in formal schools - they're passed from master to apprentice in guilds that have existed for centuries. A master plasterer (gebs) might spend 10 years as an apprentice before being allowed to work on important buildings. This ensures continuity of techniques that would otherwise be lost.

The layered history visible in every building facade

If walls could talk, these would have PhDs in history. You can see where buildings have been modified over centuries - a doorway filled in here, a window added there, repairs made with slightly different materials. It's like geological strata, but for human habitation. Each layer tells a story of the people who lived there.

The canyon-like feeling of Fes el-Bali's narrowest streets

The height-to-width ratio of these streets creates what urban designers call "street canyon" effects. In summer, they stay cool because the sun can't reach the ground. In winter, they're protected from wind. The orientation isn't random either - main streets often run east-west to maximize shade, while smaller alleys branch off at angles.

The beautiful textures created by centuries of weathering and repair

The walls aren't smooth like modern construction - they have texture from the hand-applied plaster, repairs made at different times, and weathering from centuries of sun and rain. This texture catches the light in ways that flat walls never could. It's a quality that's impossible to fake - you can only get it through time.

The complex web of alleys that makes up Fes el-Bali's urban fabric

After what feels like miles of winding alleys (but is probably only a few hundred meters as the crow flies), we're getting close to our accommodation. The cart handler knows exactly where he's going - he could probably do this route blindfolded. For us, every turn looks like every other turn. It's disorienting in the best possible way.

|

| Continuing through the maze of alleys to our riad - the adventure continues! |

Our riad is one of Fes el-Bali's numerous dars (houses with central courtyard) that offers rooms to tourists. Perhaps due to lingering effects of the pandemic, we are the only guests in the 7 or so available rooms. We are given the best room of the dar: the only room on the roof terrace with a small courtyard looking out over the medina of Fez. Score!

|

| The unassuming entrance to Dar Mfaddel - never judge a riad by its door! |

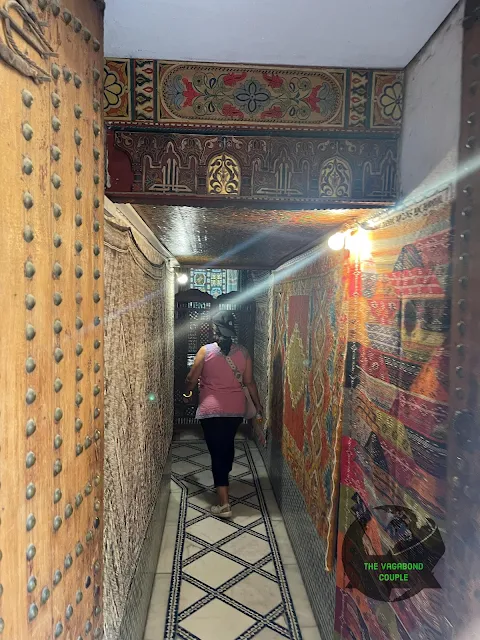

We check in to our B&B. The inside of our dar is exquisite. From the outside, it's just another door in a wall. Inside, it's a palace. This is classic Moroccan design - modest exteriors hiding lavish interiors. It comes from both Islamic humility and practical security. Why advertise your wealth to potential thieves?

The breathtaking central courtyard of Dar Mfaddel

The courtyard (known as a patio in Spanish or wast ad-dar in Arabic) follows the classic riad design: rooms opening onto a central open space, often with a fountain or garden. This design maximizes privacy while providing light and ventilation to all rooms. The fountain isn't just decorative either - it humidifies and cools the air through evaporation. Medieval air conditioning!

|

| The intricate zellij tilework and plaster carvings of Dar Mfaddel |

Dar Mfaddel is owned and run by Hicham and his wife who are an extremely friendly couple but speak French and Arabic far more fluently than English. They welcome us with homemade snacks and mint tea which we happily gulp down while completing the paperwork. Moroccan hospitality is legendary for a reason - even the paperwork comes with refreshments!

Traditional Moroccan seating with colorful cushions and low tables

The mint tea (atay b'naanaa) isn't just a drink - it's a ritual. The pouring height creates foam, which is considered a sign of good tea. The proper way is three servings: the first as bitter as life, the second as strong as love, and the third as gentle as death. We're definitely on the "gentle as death" round after that long journey!

The harmonious proportions of traditional Moroccan architecture

The architecture follows specific proportional systems. The height of rooms relates to their width, doorways follow golden ratios, and spaces flow into each other in carefully considered sequences. It's not random beauty - it's calculated elegance based on principles developed over centuries.

The beautiful cedar wood ceiling typical of Fassi architecture

The ceilings are made of cedar wood from the nearby Middle Atlas mountains. Cedar has natural insect-repelling properties and a wonderful scent that fills the room. The geometric patterns in the woodwork (known as gear) are cut by hand using techniques unchanged for centuries. Each piece is fitted together without nails - it's all joinery.

The layered spaces creating visual depth and interest

Notice how you can see through multiple spaces? This is intentional - it creates visual connections while maintaining physical separation. The arches frame views like pictures, guiding your eye through the space. It's architecture as visual poetry.

The play of light through different levels of the riad

The light changes throughout the day as the sun moves. Morning light hits one side, afternoon light another. The white walls reflect light into shadowed areas. At night, lanterns create pools of warm light. The architects understood light as a material to be shaped, not just something that happens.

Looking up through the levels creates a sense of wonder

Looking up through the open center gives you that "looking up from the bottom of a well" feeling, but in a good way. You can see all the way to the roof, with balconies and walkways at different levels. It creates vertical connections while maintaining privacy - you can hear life in the house but not necessarily see it.

The upper levels where family life would traditionally occur

In traditional Moroccan homes, the ground floor was for receiving guests (the salamlek), the first floor was for family (the haramlek), and upper floors were for sleeping. The rooftop was for laundry, drying food, and enjoying evening breezes. Each level had its purpose in the domestic rhythm.

|

| Dar Mfaddel - a perfect example of traditional Fassi architecture |

The final flight of stairs leads to the third-floor terrace on the roof. The steps are way more steep than we are used to. The last three steps need special attention due to being especially narrow and turning sharply. Even the widest part of these final steps are smaller than our feet. This isn't a design flaw - steep stairs take up less space, and in a dense medina, every square foot counts. Also, they're harder for invaders to climb quickly. Medieval security feature!

|

| The famously steep stairs to the roof - medieval StairMaster included! |

Hicham is kind enough to haul our luggage up to our room. We would have otherwise had great trouble climbing those last few stairs with our luggage ourselves. The terrace itself is beautiful. The room is comfortable with air-conditioning and tiny but clean and fully functional attached bathroom with plenty of available hot water. After desert camping, this feels like the Ritz!

Our roof terrace room - worth every steep step!

The rooftop terrace is traditionally where women would gather, do laundry, dry food, and socialize away from male visitors. It was (and still is) a feminine space in many ways. Today, it's where guests drink tea and watch the sunset over the medina. Some traditions evolve beautifully.

The roof terrace - urban oasis above the bustling medina

The roof is paved with traditional zellij tiles in geometric patterns. These aren't just decorative - the small tiles allow for expansion and contraction with temperature changes without cracking. The patterns also help with drainage. Every beautiful thing here has a practical reason for being beautiful.

The roof offers protection and perspective on the medina below

From the roof, you can see how the buildings cluster together, sharing walls for structural stability and thermal mass. The flat roofs (terraces) create a "fifth facade" - from above, the medina looks like a honeycomb of courtyards and light wells. It's a completely different city from this perspective.

Our room blends traditional design with modern comfort

The room follows traditional design with modern updates. The thick walls provide thermal mass, keeping it cool in day and warm at night. The small windows (with shutters) control light and ventilation. The air conditioning is discreetly added without破坏ing the aesthetic. It's heritage conservation done right.

|

| Penthouse terrace room on roof of Dar Mfaddel - medieval luxury! |

There is a view of the Medina of Fez from our penthouse lodging. We can see rooftops, minarets, and the hills beyond. At night, we'll hear the call to prayer from multiple mosques creating a beautiful stereo effect. By day, we'll hear the sounds of the medina filtering up - merchants calling, children playing, the general hum of life.

The sea of rooftops that makes up Fes el-Bali

From up here, you can see how the city follows the contours of the hills. The highest points have the most important buildings (mosques, madrasas), both for visibility and defensibility. The lower areas are more residential. Water flows downhill through the covered river channels, powering mills and fountains along the way.

|

| Views of Fes el Bali from roof terrace of Dar Mfaddel - absolutely priceless |

We head out a bit later in the evening for dinner and walk down derb (street) Agoumi Zkak Lahjar next to our dar. As we learned in the medina of Marrakech (see Marrakech: Daughter of the Desert and Atlas Mountains), every neighborhood of these ancient Moroccan walled cities has a saqaaya (fountain) at its entrance for people to perform ablution (traditional washing of face, hands and feet in Islamic culture) before entering. This particular saqayya at the intersection with derb Agoumi Zkak Lahjar is called "Fontaine el-Hassaniya".

|

| Fontaine el Hassaniya - the neighborhood fountain for ritual purification |

Fountains like this weren't just for ritual washing - they were social hubs, news centers, and community gathering spots. Women would come to collect water (though most homes had their own wells), people would stop to drink, children would play around them. The sound of flowing water was considered calming and spiritually uplifting.

|

| derb Agoumi Zkak Lahjar - our home street in Fes el-Bali |

We head towards a Moroccan restaurant called "Dar Khabya" which is up this street according to google maps. This is also our first opportunity to have a little shopping fun in the medina of Fez. The shops are just closing for the evening, but we get a preview of what we'll see tomorrow. Leather goods, ceramics, spices, lanterns - it's a sensory overload in the best way.

Evening brings a different atmosphere to the medina streets

The medina changes character at night. The tourist shops close, but the local life continues. People are out visiting, children play in the alleys, families sit in doorways. The lighting creates pools of warmth in the darkness. It feels more intimate, more real somehow.

|

| derb Agoumi Zkak Lahjar takes on a magical quality at night |

A local young boy senses we are looking for dinner and insists on taking us to his house. He also tells us Dar Khabya is closed. We follow him into his house and up the stairs to their terrace to find an open-air restaurant on the roof with a parapet around it. We missed the name of this roof-top restaurant but it is at 34°03'51.5"N, 4°58'36.9"W. This is the medina way - personal connections matter more than online reviews.

|

| Rooftop restaurant on derb Agoumi Zkak Lahjar - family hospitality at its best |

The terrace restaurant is wholly run by the family of the house. Children of the family speak excellent English. One of the young daughters brings us a menu and takes our order. This is how many businesses work in the medina - family enterprises where everyone contributes. The kids learn English in school and help with the business. It's entrepreneurship 101, medina-style.

There are excellent terrace-top views of Fes el-Bali for us to marvel at while waiting for food. We can see the tall minaret of R'cif Mosque. Is that the minaret of Bou Inania Madrasa at the horizon? The sunset paints the sky in oranges and purples, and the first stars begin to appear. The call to prayer echoes from multiple mosques, creating a beautiful layered sound.

|

| Panorama of Fes el-Bali from rooftop restaurant on derb Agoumi Zkak Lahjar |

The food arrives - tagine cooked the traditional way, slow-cooked in earthenware pots. The flavors are incredible: preserved lemons, olives, spices that have traveled these trade routes for centuries. We have couscous, fresh bread, and more mint tea. Everything tastes better with this view.

|

| View of Fes el-Bali from rooftop restaurant as evening settles in |

The bill for a lavish dinner for the two of us comes in at Moroccan Dirham equivalent of US$ 25. Running short of Moroccan dirhams, we want to pay in US dollars, that too with a $100 bill hoping to get change back in dirhams. We ask one of the daughters to see if we can speak to her father. The sweet little girl initially reacts with apprehension asking us if something was wrong with the food and the service. She is visibly relieved when we explain the reason we need to talk to a grown-up.

The young girl fetches her dad. The father is then joined by an uncle and we work out a decent deal for the exchange rate, getting back 750 dirhams in cash which is significant amount of money in Morocco. This informal exchange system works because of trust - something that's still strong in close-knit communities like this.

By the time we get back to our dar, it has become eminently clear that we will be totally lost in Fes el-Bali without a guide. It is quite late at about 10 PM but we call Hicham anyway to request help with having a guide meet us here the very next morning. Despite the very short notice, Hicham does not hesitate to tell us a guide will pick us up at 9 AM in the morning and he will charge us US$ 50 to take us on a six-hour (or less if we wish) walking tour of Fes el-Bali.

A long day that started on the Erg Chebbi wind-blown sand dunes in Merzouga comes to an end. We hit the bed tired but anticipating the next day with excitement. As we fall asleep, we can hear the sounds of the medina settling down for the night - distant conversations, a cat meowing, the occasional scooter puttering through an alley. It's the soundtrack of a city that's been alive for twelve centuries.

July 16, 2023

Fes el Bali is quiet at dawn. A gentleman on a bicycle comes through the alley with loaves of bread. A lady buys bread from him on the derb. He then delivers a bag full of bread to our dar, leaving the bag at the door. This is the morning bread delivery - fresh khobz (Moroccan bread) baked in neighborhood ovens. Most homes don't have ovens, so they take their dough to the local bakery to be baked. The delivery man brings it back still warm.

Dawn in Fes el-Bali - the city wakes gently

The first call to prayer (Fajr) happens before sunrise. It's the quietest of the five daily prayers, with just a few faithful making their way to the mosque in the pre-dawn light. The muezzin's voice seems to come from everywhere and nowhere in the maze of alleys.

The morning bread delivery - a daily ritual unchanged for centuries

The bread isn't just food - it's part of the social fabric. Breaking bread together creates bonds. If you drop bread, you pick it up and kiss it as a sign of respect. Bread is considered a blessing from God. This daily delivery connects households to the community bakery, creating networks of interdependence.

|

| Early morning bread delivery - the human infrastructure of the medina |

A house cat smells fresh bread. Cats are everywhere in the medina - they're considered clean animals in Islam (unlike dogs) and help control rodents. There's even a saying: "If you kill a cat, you need to build a mosque to be forgiven." They're part of the ecosystem, both practical and beloved.

|

| Cat - the unofficial guardians of Fes el-Bali |

An excellent breakfast is cooked and served hot by Hicham himself. Our guide arrives punctually at 9 o'clock and we start exploring the medina of Fez. The guide's name is Ahmed, and he's been doing this for 20 years. He knows everyone and everything about Fes. We're in good hands.

|

| Leaving for Fes el-Bali walking tour - with a guide this time! |

Outside the Medina of Fez: Fontaine Batha

We start by heading back west to the general area of the Batha Fountain just north of Oued (river) Zibal. This will take us close to where we were dropped off yesterday outside the old city. Ahmed explains that "Batha" means "open space" in Arabic - it was one of the few open areas inside the city walls, used for markets and gatherings.

We get our first lesson of navigating the alleys of Fes el-Bali from our guide. Street names in hexagonal signs convey dead ends and those in rectangular signs are thruways. For example the following sign says Derb Smiyet Sidi is a dead end. This system was implemented in the 1990s to help with navigation. Before that, there were no street signs at all - you just had to know.

|

| Hexagonal road sign representing a dead end - don't go this way unless you live there! |

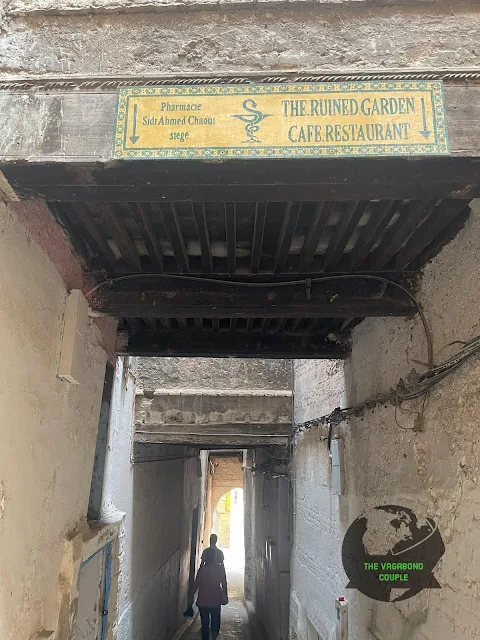

In the following example, the sign for Derb Sidi Ahmed Chaoui says it is not a dead end. The French "Rue" and Arabic "Derb" are used interchangeably in Morocco to refer to "street". Ahmed explains that "Sidi" means "saint" or "holy man" - many streets are named after local saints whose tombs are in the neighborhood.

|

| Rectangular road sign indicated throughway (not dead end) - this way to adventure! |

We continue west. Ahmed points out architectural details we missed yesterday: the different styles of door knockers (heavy ones for men's entrances, lighter ones for women's), the way some houses have small shelves by the door for milk deliveries, the carved stone thresholds worn smooth by centuries of footsteps.

Morning light creates different shadows than evening light

The quality of light is different in the morning - sharper, clearer. The shadows have hard edges. As the day progresses, the light will soften. Photographers know that the "golden hour" after sunrise and before sunset is best for photos, but every hour has its own quality in the medina.

With a guide, we notice details we missed yesterday

Ahmed explains that the medina is divided into neighborhoods called "hawma," each with its own mosque, fountain, bakery, and hammam (bathhouse). This creates self-sufficient units within the larger city. People rarely need to leave their hawma for daily needs. It's hyper-local living centuries before it was trendy.

Our guide Ahmed knows every alley and its history

We reach a pretty square the intersection of Ave de La Liberte and Rue El Douth. The decorated doors of Heritage Boutique Hotel are on one side of the square. Ahmed explains that this area just outside the medina walls was developed in the early 20th century during the French protectorate. The architecture is a blend of Moroccan and French colonial styles.

|

| Fes heritage boutique hotel - where traditional meets colonial architecture |

We head north to Morocco's Proclamation of Independence Monument (Monuments de manifestation de l'indépendance). A large replica of handwritten Manifesto of Independence of Morocco of January 11, 1944 in Mabsout Maghrebi script is displayed here. "On January 11, 1944, with the outcome of World War II still uncertain to all but the most perceptive, 66 Moroccans signed the public proclamation demanding an end to colonialism and the reinstatement of Morocco's independence, an enormous risk at the time", says wikipedia. "Among the signatories were members of the resistance, symbols of a free Morocco, and people who would become key figures in the construction of the new Morocco."

January 11 is an official government holiday in Morocco. Ahmed adds that many of the signatories were from Fes, which has always been a center of learning and political thought. The city produced many of Morocco's intellectuals and leaders.

|

| Monument of January 11, 1944 Proclamation of Independence of Morocco |

Back into the Medina of Fez through Bab Bou Jeloud (Blue Gate)

We reach a landmark of Fes el-Bali a bit further up north. The Bab Boujeloud gate (Blue Gate of Fes) stands looming over the street marking the west entrance to old medina of Fez. The gate was built relatively recently by the French in 1912. The much smaller and far less lavish original gate still exists next to it.

The French did a good job with mosaic tiles and Arab and Moroccan motifs. The western side of Bab Boujeloud (as one walks east into the old medina of Fez) is blue. The opposite side of the gate is actually green representing Islam. Ahmed jokes that it's like a mood ring for the city - blue when you're feeling cosmopolitan outside, green when you're feeling spiritual inside.

Interestingly the doors of the gate can be bolted and locked only on the outside (west side). People inside the old city can be locked in from outside. This was for security - if there was trouble in the city, authorities could lock the gates to contain it. Today, they're never locked, but the mechanism remains.

|

| Bab Bou Jeloud: Blue Gate of Fes, west side - the famous blue ceramics |

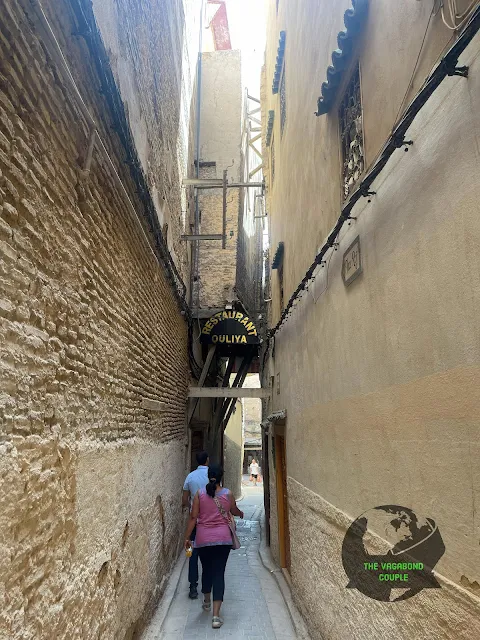

We walk through the gate back into the car-free medina. There are numerous restaurants and souvenir shops. The minaret of Bou Inania mosque is visible in the distance. Ahmed explains that this area just inside Bab Bou Jeloud is the most touristy part of the medina. As we go deeper, we'll find more authentic areas.

The bustling scene just inside Bab Bou Jeloud gate

The area immediately inside the gate is like a decompression chamber between the modern city and the medieval medina. There are restaurants with multilingual menus, shops selling souvenirs to tourists, and plenty of guides offering their services. It's lively, colorful, and a bit overwhelming.

|

| Fes el-Bali immediately behind Bab Boujeloud gate - the adventure begins! |

Turning around to to look at the east face of the gate, we confirm it is indeed green. Ahmed explains that blue and green are both important colors in Islam. Blue represents the sky and water (life-giving forces), while green represents paradise and the Prophet Muhammad (who is said to have worn green). The gate thus represents the transition from the worldly (blue) to the spiritual (green).

|

| Green (east) side of Bab Bou Jeloud viewed from inside Fes el-Bali |

Dar al-Magana: The Gravity-Powered Water Clock of Fes

Having just entered Fes el-Bali through Bab Bou Jeloud (Blue Gate), we walk through a charming old covered bazaar towards Rue Talaa Kebira. The covered area provides shade and creates a cool microclimate. Ahmed explains that different sections of the bazaar specialize in different goods - this area is mostly for tourists, but further in we'll find the real craft workshops.

The covered bazaar provides relief from the sun and creates a market atmosphere

The covered passages (known as "kissarias") were where valuable goods like silk, spices, and jewelry were sold. They could be closed off at night for security. Today, they still house shops, though the goods have changed somewhat. The architecture creates natural air conditioning - the high ceilings allow hot air to rise, while the shade keeps the ground level cool.

|

| Bab Bou Jeloud gate towards Rue Talaa Kebira - following the main artery |

Rue Talaa Kebira and Rue Talaa Sghira to its south are two streets that cross Fes el-Bali all the way to the east end at Bab Rcif gate which we will reach later. Getting back on either of these two streets is a quick way to get your bearings back after invariably getting lost in Fes el-Bali. "Talaa" means "ascent" - these streets climb from the river valley up the hill. "Kebira" means "big" and "Sghira" means "small."

A right on Rue Talaa Kebira and a short walk gets us to the famous gravity (weight) powered water clock of Fes: the Dar al-Magana (House of the Clock). This was commissioned in the 14th century by Sultan Abu Inan Faris of Marinid dynasty as a part of the greater Bou Inania complex. Ahmed explains that "magana" means "clock" in Arabic, and this was one of several public clocks in medieval Fes.

|

| Water Clock of Fes: Dar al-Magana at left - medieval engineering marvel |

From the outside, the weight powered water clock of Fes looks like a great work of mechanical and hydraulic engineering. It is also decorated intricately in carved wood and stucco (mix of lime, sand and water). Ahmed points out the Kufic inscriptions around the windows - they're verses from the Quran about time and its passage. The whole structure is a meditation on time, both physically and spiritually.

|

| Fez Morocco Water Clock, Dar al-Magana, Fes el Bali - a masterpiece of medieval engineering |

There are twelve square windows near the top of the building. The long rafters below and in between the square windows used to hold a roof up and are not part of the clock. The shorter studs centered below each window have corresponding studs further down below the arched windows. These lower studs used to have brass bowls which are not there now (they were taken away in 2004 as part of an effort to repair the clock).

|

| Fez Morocco Gravity Powered Water Clock, Dar al-Magana, Fes el Bali - the intricate mechanism |

In an operational state, a door behind each of the square windows at the top would open up in turn and drop a metal ball on the hour every hour. The ball would drop onto the corresponding brass bowl catcher below. There was some sort of a pusher behind the square windows that would travel left to right between two adjacent windows in exactly one hour. This was powered by a weight on one end and a float on a column of water on the other end. The water was calibrated to flow out and cause the floating weight to drop at a rate that would move the pusher between one window to the next exactly in one hour. The clock would keep working as long as there was water for the float to steadily drop down. Assumedly the water was refilled periodically.

Unfortunately nobody today knows exactly how this clock operates, though there is an ongoing effort to figure it out and get it going again. Here is a picture of the clock from early 20th century with the bowls still in place.

|

| Dar al-Magana in the beginning of the last century with bowls still in place |

Bou Inania Madrasa (and Mosque with Minaret)

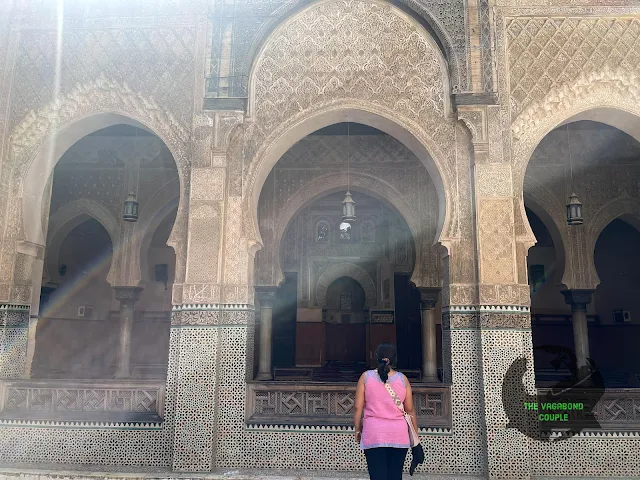

The stunning Bou Inania Madrasa is right across Dar al-Magana. Unlike Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakech which stands as a theological school separately from the mosque and minaret next to it, Bou Inania is a rare madrasa that is also a mosque itself with its own minaret. Friday Islamic prayer congregations held inside Bou Inania make it a religious building. However it remains one the few Moroccan religious monuments that is open to everyone. What's fascinating is how Marinid architecture blended function with beauty—every decorative element served both aesthetic and symbolic purposes, from the geometric patterns representing infinite divinity to the floral motifs symbolizing paradise.

|

| Bou Inania Madrasa courtyard composite showing the symmetrical perfection of Marinid architecture—every tile was cut by hand using techniques unchanged since the 14th century |

The minaret at the northwestern corner of Bou Inania can be seen from Bab Bou Jeloud (the blue gate). Medieval minaret design wasn't just about height—it was about acoustics. The shape and multiple openings amplified the muezzin's call across the entire medina. Some engineers claim the ancient builders understood sound physics better than we give them credit for.

|

| Minaret of Bou Inania madrasa & mosque behind courtyard—the green tiles indicate religious function while the geometric patterns prevent idolatry in Islamic art |

Fez's microclimates create fascinating preservation challenges. The morning condensation that forms in these narrow alleys actually helps preserve the plasterwork by keeping it slightly moist, while the afternoon sun bakes it hard. It's like natural climate control invented 800 years before HVAC systems.

Bou Inania Madrasa was commissioned in the 14th century by, and named after, Sultan Abu Inan Faris who also commissioned the Dar al-Magana water-clock. It stands as a testament to the architectural and artistic heights reached during rule of the Marinid dynasty. This sultan was particularly obsessed with timekeeping—hence funding both a madrasa and an elaborate water clock across the street. Historians suspect he had clock envy from European visitors.

The madrasa has two entrances: the front door on its northwest side on Rue Talaa Kebira opposite the Dar al-Magana water clock building, and a rear door on its southeast side on Rue Talaa Sghira. We enter the madrasa from the large brass front door with a decorated arch into a grand marble courtyard. There is a low round fountain in the middle of the courtyard which can be used for ablution.

|

| Courtyard of Bou Inania madrasa showing perfect symmetry—the fountain's position creates cooling evaporation while the tiles direct rainwater toward hidden cisterns |

Constructed of cedar wood, brick, stucco and tiles, Bou Inania madrasa is exquisitely sculpted, carved and decorated. The cedar came from the Middle Atlas mountains, carried by donkey trains along ancient trade routes. Each piece was selected for grain pattern and aromatic quality—the scent was considered part of the spiritual experience.

There are beautiful cedar lattice screens between pillars around the courtyard. A passage behind the screens leads into classrooms and common rooms of the madrasa. Stairs at two corners of the passage lead to dorms on the upper floor. Student life here followed strict rhythms: prayer, study, meals, sleep—all timed by the water clock across the street. No snooze buttons in 1350.

|

| Courtyard of Bou Inania madrasa featuring cedar mashrabiya screens that filter light while maintaining privacy—Medieval architectural genius |

Water flows along a little channel along the prayer hall side of the courtyard. Water from Fes river's el-Lemtiyyin canal is channeled through here. The prayer hall beyond the courtyard is accessed over little bridges at corners. This hydraulic system wasn't just decorative—it cooled the building through evaporation and provided sound masking for private conversations. Ancient Moroccan architects were the original HVAC engineers.

|

| Courtyard of Bou Inania madrasa showing water channel system—these mini-aqueducts kept the temperature 10-15°F cooler than outside |

The general pattern of the pillars and walls is mosaic of zellij tiles at the bottom, a thin band of sgraffito tiles above it and stucco decoration at the top. There is finely carved wood above the stucco reaching up to the roof. This vertical hierarchy wasn't random—tiles at the bottom resisted scuffing, plaster in the middle showed detailed calligraphy, and wood at the top provided structural support. Every material was used where it made practical sense.

|

| Prayer hall of mosque inside Bou Inania Madrasa—the mihrab's alignment toward Mecca is precise to within 0.5 degrees, calculated using 14th-century astronomy |

The prayer hall is the mosque part of the madrasa and only Muslims can cross into it over the water channel. However, the mosque is openly visible from the courtyard giving us an opportunity to appreciate its beauty including gorgeous colored glass windows above and to the sides of the mihrab. The colored glass creates rainbow patterns that move across the floor throughout the day—a literal light show timed by the sun.

|

| Prayer hall and mihrab showing mastery of light manipulation—the stucco patterns cast ever-changing shadows throughout the day |

The prayer hall has a front and rear part divided by stucco arches on columns made of marble and onyx. This division served acoustic purposes—the front section amplified the imam's voice while the rear absorbed echoes. Medieval worship wasn't just spiritual; it was multisensory engineering.

|

| Prayer hall and mihrab showing column placement that creates perfect sightlines from every prayer position |

Medieval education here was surprisingly progressive. Students studied mathematics, astronomy, medicine alongside theology. The courtyard layout facilitated "walking debates"—students would pace around the fountain discussing philosophy while the sound of water masked their conversations from eavesdroppers. Academic freedom, 14th-century style.

Unlike Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakech, visitors are limited to pretty much the central courtyard of Bou Inania Madrasa. Though we were not able to walk around the entire building freely, there is enough ancient architectural and artistic wizardry here to keep us agape for a long time. Our guide Ahmed joked that "even the walls have PhDs here"—and given the intellectual history, he might be right.

Exiting Bou Inania through the front door, we get back on Rue Talaa Kebira. Turning south, we go through vibrant bazaars towards Rue Talaa Sghira. The transition from sacred space to commercial chaos is immediate—one minute you're contemplating divine geometry, the next you're dodging donkey carts loaded with leather goods. Fez doesn't believe in gentle transitions.

|

| Bazaar between Rue Talaa Kebira and Rue Talaa Sghira east of Madarasa Bou Inania—notice the roof beams protecting from sun while allowing ventilation |

The medina's commercial districts follow ancient zoning laws that haven't changed much since the 9th century. Metalworkers cluster near water sources for cooling, tanners downstream (for obvious smell reasons), food vendors near residential areas. It's medieval urban planning that actually makes sense once you understand the logic.

|

| Bazaar between Rue Talaa Kebira and Rue Talaa Sghira east of Madarasa Bou Inania showing traditional shop organization by craft guilds |

Abu al-Hasan Mosque

We head east on Rue Talaa Sghira to Abu al-Hasan Mosque (Abou El Hassane El Marini Mosque). Unable to enter the mosque, we continue east. The mosque dates to the 14th century and represents the transition from Almohad to Marinid architectural styles—notice how the minaret incorporates both square Almohad simplicity and later decorative elements. It's like architectural evolution frozen in stone.

|

| Closed entrance of Abu al-Hasan Mosque at right showing traditional hinge design that distributes weight across massive doors |

Mosque architecture in Fez follows precise astronomical alignment. The qibla wall (facing Mecca) is calculated using both mathematical formulas and celestial observations. Some medieval mosques here are more accurately aligned than modern buildings using GPS. Ancient scholars knew their stuff.

|

| Closed windows of Abu al-Hasan Mosque showing mashrabiya screens that provide privacy while allowing air circulation—Medieval air conditioning |

Talaa Saghira Fountain

The Talaa Saghira Fountain is among Fes el-Bali's most gorgeous mosaic-decorated saqayya, though it does not have a decorated wooden canopy like Nejjarine Fountain in the heart of Medina which we will visit later. Fontaine Talaa Saghira is on Rue Talaa Sghira right after Abu al-Hasan Mosque. Public fountains like this weren't just decorative—they were social hubs where women gathered, news was exchanged, and community bonds strengthened. The sound of flowing water also masked private conversations in a city where privacy was scarce.

|

| Talaa Saghira Fountain showing intricate tilework—each piece cut by hand using techniques passed down through generations of artisans |

Barbary Fig: Cactus Fruit

We spot a vendor selling barbary fig (prickly pear) from a cart on Rue Talaa Sghira. These are fruits that grow once a year on top of barbary fig cactus plants (Opuntia ficus-indica) which are endemic to Mexico but are also found in desert zones of North Africa. The stems of the plants are also edible. The simplest way to consume these fruits is to peel off the thorny skin and eat the flesh inside, seeds and all. Processed products derived from it include juices, jams, candies and even wine.

The Spanish call this fruit "tuna." The cactus was introduced to North Africa in the 16th century and became naturalized so thoroughly that many Moroccans assume it's native. It's particularly useful in erosion control—the roots hold soil together in arid regions. Every part gets used: fruit for eating, pads for animal feed, spines for... well, we learned not to touch those the hard way.

|

| Vendor selling Barbary Fig from a cart on Rue Talaa Sghira—the different colors indicate ripeness levels from tart green to sweet purple |

It is almost 11 o'clock. Although nowhere as hot as we experienced in Marrakech or Erg Chebbi dunes on Sahara Desert, it is hot enough for us to get something to cool down. We get off Rue Talaa Sghira into narrow alleys lined with little shops and buy cold drinks and ice-cream. The shopkeeper tells us his family has run this store for three generations. "My grandfather sold to French soldiers during the protectorate," he says with a wink. "Now I sell to tourists. Same heat, different customers."

|

| General Store / Mini Market: Cold water, cold drinks and ice-cream—note the vertical storage maximizing limited floor space in narrow shops |

From Rue Talaa Sghira, we take Derb Zerbtana going southwest to check out the fancy entrance of the five-star Riad Fes Relais & Châteaux hotel that is about 10 times more expensive than the beautiful dar we lodged at. The contrast between traditional housing and luxury tourism is stark here. One alley over, families live in centuries-old homes; here, wealthy tourists pay €800/night for "authentic experience." Our guide Ahmed jokes, "They pay for what we grew up trying to escape."

Hotel Riad Fès - Relais & Châteaux entrance showing restoration of traditional elements with modern luxury amenities

The restoration of historic buildings into luxury hotels presents fascinating challenges. Traditional riads had shared bathrooms, no electricity, and were organized around family life. Converting them to modern standards while preserving architectural integrity requires balancing authenticity with comfort. The best restorers use original materials and techniques—hand-cut tiles, lime plaster, cedar wood—but add discreet modern systems.

|

| Hotel Riad Fès - Relais & Châteaux interior showing traditional courtyard design adapted for luxury hospitality |

On towards Bab Rcif

We continue east on Derb Sefli towards Rue Sidi Mohammed Belhaj, crossing Muhammad Al-Qura School on the way. Traditional Quranic schools like this one represent Morocco's long educational history. Students memorize the entire Quran—over 6,000 verses—a process taking 3-5 years. The rhythmic chanting creates a soundscape that's been part of Fez for centuries.

Muhammad Al-Qura School entrance showing traditional Islamic educational architecture with central courtyard design

Medieval Islamic education was surprisingly progressive in some ways. While European universities focused on theology and classics, madrasas in Fez taught mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy alongside religious studies. The courtyard layout facilitated what we'd now call "active learning"—students moved, debated, and learned through discussion rather than passive listening.

|

| Muhammad Al-Qura School courtyard showing adaptation of traditional madrasa design for modern educational needs |

The soundscape of Fez reveals its layered history. At any moment you might hear Quranic recitation from a school, the clang of metalworkers, donkey hooves on stone, call to prayer, and vendor calls. It's like auditory archaeology—each sound represents a different century of the city's life.

Eastbound Derb Sefli showing typical alley width and construction—narrow enough for shade, wide enough for commerce

|

| Eastbound Derb Sefli towards Rue Sidi Mohammed Belhaj showing adaptive reuse of spaces over centuries |

Taking a right on southbound Rue Sidi Mohammed Belhaj, we walk towards the next intersection with Rue Seyaje (Dar Siaj) on which we make a left to walk east towards Hotel Fes. The saqaya of Siaj fountain is on this lane. These neighborhood fountains served as early social media—gossip, news, and matchmaking all happened around water collection. The best fountains had the best acoustics for private conversations.

|

| Rue Sidi Mohamed Belhaj showing mixed-use medieval urban planning—homes above, commerce below |

Medieval urban planning here followed principles we're rediscovering today: mixed-use development, pedestrian priority, climate-responsive design. The narrow streets create shade, the courtyard houses provide private outdoor space, and the dense clustering reduces energy needs. It's like a 9th-century version of sustainable city design.

Dar Siaj, Rue Seyaje showing gradual architectural changes from simple plaster to decorative elements

|

| Rue Seyaje showing organic urban development—buildings added and modified over centuries without master planning |

Dar Siaj becomes more interesting as it rapidly slopes downwards as we approach the Abderrahim antique store where the dar ends and leads into charmingly narrow paths between houses. The slope isn't accidental—it follows natural topography and directs rainwater toward the river. Medieval engineers worked with nature rather than against it.

Rue Siaj showing dramatic slope—each step represents careful water management and pedestrian circulation planning

The geology beneath Fez tells a story of ancient rivers and seismic activity. The city sits on alluvial deposits from the Fez River, which explains why some areas sink while others remain stable. Traditional builders understood this intuitively—they used flexible lime mortar that could shift without cracking, and built foundations that "floated" on the unstable soil.

|

| Dar Siaj antique shop showing preservation of traditional commercial spaces in changing urban context |

We take the alley south between houses at the end of Dar Siaj. This is one of the paths not present in google maps. We later edited google maps and submitted requests for updates to google. It's humbling to realize that even in the age of satellite imagery, there are places only known to locals. The medina keeps some secrets digital mapping hasn't uncovered.

We continue to descend rapidly along this unmapped path all the way to Derb Rechm at Riad Laayoun. The descent feels like moving through geological layers—each turn reveals different building periods, materials, and techniques. It's vertical urban archaeology.

Dar Siaj to Derb Rechm transition showing how medieval cities grew organically without formal street grids

The social structure of traditional medina neighborhoods centered around the "derb"—not just a street, but a community. Residents of a derb shared water sources, protected each other's homes, and intermarried. Even today, you can see how architectural features like shared courtyards and interconnected roofs facilitated this communal life.

Dar Siaj to Derb Rechm showing preservation of traditional urban fabric despite modern pressures

Historical records show that Fez faced multiple crises—plagues, fires, political upheavals—yet always rebuilt using traditional techniques. After the 1912 fire that destroyed much of the medina, reconstruction followed original plans because the knowledge was preserved in guilds and families. It's resilience through cultural memory.

Dar Siaj to Derb Rechm showing how urban spaces evolve while maintaining cultural continuity

The environmental wisdom embedded in traditional architecture is remarkable. Thick walls provide thermal mass, small windows reduce heat gain, courtyards create microclimates, and water features add evaporative cooling. It's passive solar design perfected centuries before the term existed.

Dar Siaj to Derb Rechm showing integration of architecture with natural topography and hydrology

Architectural details tell stories of cultural exchange. The pointed arches show Andalusian influence, the geometric patterns reflect Persian mathematics, the courtyard design comes from Roman villas via Islamic adaptation. Fez isn't just Moroccan—it's a crossroads of civilizations.

Dar Siaj to Derb Rechm showing architectural details that reveal centuries of cultural exchange and adaptation

Urban life in traditional medinas followed rhythms dictated by climate and religion. Morning hours were for commerce, midday for rest, evening for socializing. The call to prayer marked time before clocks were common. Even today, you can feel these ancient rhythms beneath the surface of modern life.

Dar Siaj to Derb Rechm showing architectural continuity despite centuries of change and adaptation

Historical preservation in Fez faces unique challenges. Traditional materials like tadelakt plaster and hand-cut tiles require skilled artisans, many of whom are aging without apprentices. Some restoration projects train young people in ancient techniques, creating jobs while preserving heritage. It's cultural conservation through economic development.

Dar Siaj to Derb Rechm showing how traditional urban design creates intimate, human-scale spaces

The environmental impact of traditional medina life was surprisingly low. Dense housing reduced land use, local materials minimized transportation, passive design eliminated energy needs for heating and cooling. Walking through these alleys, you're experiencing sustainable urbanism that modern planners are trying to recreate.

Dar Siaj to Derb Rechm showing material craftsmanship that has endured for centuries through careful maintenance

Architectural innovation in traditional Fez often came from constraint. Limited space led to vertical building, scarce water led to ingenious distribution systems, hot climate led to passive cooling techniques. Necessity wasn't just the mother of invention—it was the architect, engineer, and urban planner too.

|

| Unmapped alleys from Dar Siaj to Derb Rechm, Fes—these hidden paths represent living urban history preserved through continued use |

The upper and lower knockers on ancient Moroccan doors

The doors to grand old houses in old Morocco had two metal knockers at different heights. Men knocking at the door would use the upper knocker and women would use the lower one. The sound of the two knockers were different so that people inside would know the gender of the person knocking. The idea was if a woman knocked on a door and no women were inside, the men wouldn't open the door. This system maintained social norms while allowing necessary interactions. The heavier upper knocker made a deeper sound, while the lighter lower one made a higher pitch. Some houses had three knockers—the third for children, creating a domestic communication system before doorbells.

In modern Morocco, there are security cameras over traditional entrances. It's a fascinating juxtaposition: centuries-old doors with 21st-century surveillance. One local told us, "The knockers told us who was there; the cameras show us who's there. Same purpose, different technology."

Upper knocker on door of old Moroccan house—the heavier design created deeper sound signaling male visitor

Door design in traditional Islamic architecture served multiple functions beyond security. The often-massive doors provided insulation, the metal reinforcements deterred forced entry, and the decorative elements displayed family status. Some doors incorporated hidden viewing slots or speaking grilles, allowing identification before opening. It was privacy and security engineering from an era before peepholes.

|

| Upper and lower knockers on door of traditional Moroccan house showing gender-based acoustic communication system |

On to Bab Rcif gate and Place R'cif square

We continue our pedestrian journey east on Derb Rechm and then south on Derb Lamkouass Laayoun Rcif. We get on Rue Rahbat Tben and continue into bazaars eventually taking Bulevard Ben Mohammed El Alaoui northwest to Bab Rcif gate and Place R'cif square. The transition from residential alleys to commercial streets happens gradually—first a few shops, then more, until suddenly you're in a bustling market. Medieval urban zoning was fluid, responding to neighborhood needs rather than rigid plans.

|

| Derb Rechm towards Derb Lamkouass Laayoun Rcif showing gradual transition from residential to commercial urban fabric |

The markets here seem to be more of daily household shopping type, less full of souvenir and gift shops than the western side of the medina. We see a lot of local people here purchasing fruits, vegetables, fish and meat (including camel meat) essential for running household kitchens. This is the "real" medina—where residents shop, not tourists. The rhythm is different: purposeful shopping rather than leisurely browsing, quick transactions rather than prolonged haggling.

Bazaars off Rue Rahbat Tben showing daily commerce that sustains medina life beyond tourism

Traditional market organization followed principles of efficiency and community. Perishable goods near entrances for quick access, noisy crafts farther in, smelly trades downstream. It was intuitive urban planning that minimized conflicts and maximized convenience. Modern supermarkets could learn from medieval market design.

Local market showing continuity of traditional commerce patterns adapted to modern needs

|

| Bazaars on Rue Rahbat Tben towards Bab Rcif gate showing vibrant local commerce that predates tourism |

Rue Rahbat Tben towards Ben Mohammed El Alaoui Boulevard showing integration of traditional commerce with modern urban infrastructure

Bab Rcif gate and Place R'cif square

We are now at Place Rcif, the open central square or plaza at the east end of Medina of Fez. The looming Bab Rcif gate on the south side of the square is beautifully decorated. Coming in from outside of the medina in the south, Ben Mohammed El Alaoui Boulevard goes under the gate and expands into the large Place Rcif square north of the gate inside Fes el-Bali. This area of this gate is a vibrant busy place with more local folks than tourists going about their businesses around the square and bazaars in the alleys of Fes el-Bali beyond the square.

The Bab Rcif gate is also a new 20th century gate built by the French. We wonder if its massive doors, like those of its twin Bab Bou Jeloud on the west of Fes el-Bali, can also be locked only from the outside. French colonial architecture in Morocco often blended European and Moroccan elements, creating what's now called "Mauresque" style. The gate represents both colonial power and cultural adaptation—a complicated heritage that Moroccans are still negotiating.

At this point we have walked across numerous alleys all the way from Bab Boujloud gate on the west to Bab R'cif gate on the east of Fes el-Bali. It seems a long way, but really the aerial distance between the two gates is just short of one mile (3,422.99 ft, 1.04 km). The winding route we took, following ancient paths rather than straight lines, probably tripled that distance. Medieval urban design valued experience over efficiency—the journey mattered as much as the destination.

|

| Bab Rcif gate with Place R'cif square behind showing French-colonial architectural influence on traditional gate design |

R'cif Mosque

The tall minaret of R'cif Mosque looms over the western side of Place R'cif square. The 18th-century mosque was commissioned by Sultan Moulay Slimane of Alaouite dynasty. Along with al-Qarawiyyin Mosque, R'cif Mosque was a central gathering place for protestors during the 1937 riots against French occupation. The minaret served as both religious symbol and observation post—its height provided views of approaching troops. Religious architecture often served dual purposes in times of conflict.

|

| R'cif Mosque and Minaret from south of Bab Rcif showing 18th-century architectural style during Alaouite dynasty |

Souk Sabbaghine: Dyers Market of Fes el-Bali

Walking north from Place R'cif plaza, we reach the eastern bank of Bou Khrareb river. We cross over a bridge to Tarrafine shopping mall and turn north into Souk Es Sabbaghine: Souk of the Dyers. This market traditionally specializes in color dying garments and clothing made of various materials including silk, wool and cotton. The dyers' guild here dates to the 11th century and once held monopoly rights granted by sultans. Their techniques use natural dyes from plants, minerals, and insects—madder root for red, indigo for blue, saffron for yellow. Each dye requires specific water temperatures and pH levels, knowledge passed down orally for generations.

Souk Sabbaghine showing centuries-old dyeing techniques using natural materials and traditional equipment

The environmental impact of traditional dyeing is surprisingly low compared to modern chemical processes. Natural dyes are biodegradable, the water used can be filtered and reused, and the heat comes from renewable wood sources. It's sustainable textile processing that modern industry is now trying to replicate with expensive technology.

|

| Souk Sabbaghine showing continuity of craft traditions through generations of artisan families |

The Fontaine Sabaghine (Sabaghine Fountain) provides water for dying clothes. Water is first collected in buckets by the dyers. The fountain's water comes from the Fez River system, which has specific mineral content that affects dye absorption. Different dye colors require different water sources—some need "soft" water, others "hard" water with more minerals. The dyers know which fountains provide which type, a hydrological knowledge system developed over centuries.

Fontaine Sabaghine showing traditional water source design optimized for artisanal dyeing processes

Water management in traditional dyeing involves complex chemistry. The dyers adjust pH using natural additives like vinegar or ash, control temperature through careful fire management, and time immersion based on lunar cycles (some claim full moon affects dye absorption). It's alchemy as much as chemistry, blending empirical observation with traditional wisdom.

|

| Sabaghine Fountain: Collecting water in buckets for dyeing showing continuity of traditional practices |

The collected water is then heated in metal buckets over fire. Dye is added to the water and clothes immersed and drenched in the metal bucket. Colored clothes come out of steaming metal buckets. The heat opens fabric fibers to accept dye, while the metal ions from the buckets can actually enhance certain colors. Copper pots intensify blues, iron darkens colors—the dyers understand these interactions even if they don't know the chemistry.

Traditional color dying of clothes at Souk Sabbaghine showing thermal processing that opens fabric to natural dyes

We are told it is entirely possible to re-dye garments in a different color. The dyers here can take existing dye off clothes and put a different dye on, making clothes look new. This circular economy approach—repairing and renewing rather than discarding—is embedded in traditional crafts. A garment might be re-dyed multiple times over its life, each layer of color adding to its history and value.

|

| Dying of clothes at Souk Sabbaghine showing skill in achieving consistent colors through traditional techniques |

Freshly dyed clothes, balls of dyed wool and lengths of dyed yarn are on sale as well in the souk. The colors here follow traditional palettes: indigo blues from Moroccan grown plants, saffron yellows from local crocus, madder reds from root dyes. Each color has cultural significance—blue protects against evil eye, green represents paradise, white signifies purity. The dyers aren't just coloring fabric; they're embedding meaning.

|

| Dyed clothes, wool and yarn for sale at Souk Sabbaghine showing traditional color palettes and textile craftsmanship |

Oued Bou Khrareb: Khrachfiyine Pont

Souk Sabbaghine lies along the west side of Oued Bou Khrareb which, along with Oued Bou Regreg, is a source of the ancient Oued Al-Jawahir Fes canal and reservoir based water supply and irrigation system. The water system is also called the Fes River. This hydraulic engineering masterpiece dates to the 9th century and still functions today. Water rights were allocated by intricate time-sharing systems recorded on public clocks—some water wheels turned only during specific hours for specific neighborhoods.

Khrachfiyine Pont is a great viewpoint overlooking Oued Bou Khrareb from a bridge next to Souk Sabbaghine. The river here powered water wheels for grinding grain, fulling cloth, and processing materials. The sound of water wheels was once constant background noise in Fez—a hydraulic symphony that powered medieval industry.

|

| View of Oued Bou Khrareb looking north from Khrachfiyine Pont bridge showing traditional river management for artisanal uses |

The river's flow varies seasonally, and traditional water management adjusted accordingly. Summer low flows were reserved for drinking, winter high flows for industry. This sophisticated allocation system prevented conflicts and ensured sustainable use—medieval water law at its most advanced.

|

| View of Oued Bou Khrareb river looking south from Khrachfiyine Pont bridge showing integration of river with urban fabric |

From Souk Sabbaghine, we head north on Rue Seffarine. Implausibly Fes el-Bali is becoming even more glamorous as we walk through the bazaars and past the historic Seffarine Hammam (bathhouse) towards Seffarine Square neighborhood of coppersmiths and metalware. The transition from dyeing to metalwork follows logical progression—both crafts need water and fire, and both produce goods essential to daily life. Medieval zoning wasn't random; it followed material and energy flows.

Rue Seffarine towards Place Seffarine showing transition between craft districts in traditional medina organization

Traditional hammams like Seffarine Hammam served as social centers, hygiene facilities, and even informal clinics. The steam treated respiratory issues, the scrubbing improved circulation, and the social interaction supported mental health. It was holistic wellness centuries before spa culture.

|

| Rue Seffarine towards Place Seffarine showing architectural continuity in traditional craft district |

Place Seffarine

Seffarine continues to be the souq of coppersmiths, bronze smiths and metalworkers in general from at least the middle ages. Traditional techniques of their metalcraft have been handed down over many generations. The name "Seffarine" comes from the Arabic for "coppersmiths," and records mention this square as early as the 11th century. What's remarkable is not just the continuity of craft, but the continuity of location—same families, same techniques, same place for nearly a millennium.

Tools and utensils made of brass, copper, bronze, zinc, nickel and silver finely crafted by metalsmiths using hammers, lathes, rolling mills and polishers, and decorated by artisans, are still produced and sold here. Metal products built and sold here for all kinds of budgets are used daily by Moroccan families. The items include pots, pans, buckets, incense burners, trays, teapots, tea and sugar boxes, footed strainers, kettles, couscous steamers, samovars and so on. There also are richly decorated vessels for special occasions.

|

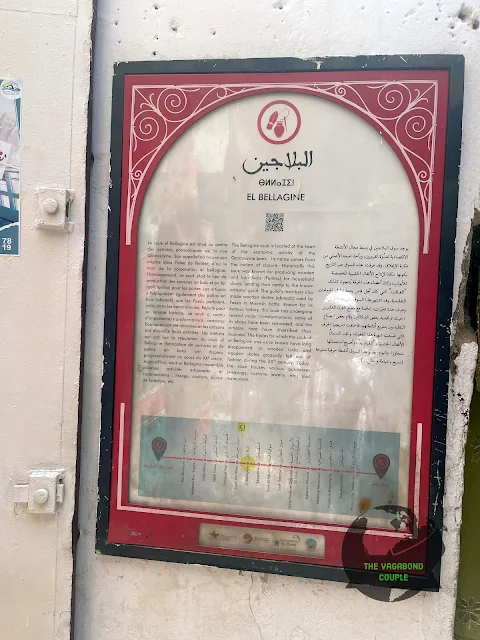

| Place Seffarine visitor information board showing historical context of medieval metalworking guilds |

In the traditional way of work here, production lines are organized consisting of workers passing increasingly complete products from one to the next in a well-defined skill-based hierarchy. Apprentices start with simple tasks like polishing, progress to basic shaping, and eventually master complex techniques like engraving or inlay. The guild system ensured quality control through peer review—master craftsmen examined each other's work, maintaining standards across generations.

|

| Building with Place Seffarine street sign showing architectural identity of historic craft neighborhood |

We will soon see entire shops overflowing with amazing metalware from Seffarine. In the meanwhile, we head up north on Dar Boutouille past Place Seffarine towards the Mosque and University of al-Qarawiyyin. The proximity of craft districts to intellectual centers wasn't accidental—scholars needed quality instruments for astronomy, medicine, and mathematics, while artisans benefited from scholarly knowledge of materials and techniques. It was medieval innovation ecosystem.

Dar Boutouille from Place Seffarine towards al-Qarawiyyin Mosque Madrasa University showing connection between craft and learning districts

The soundscape changes as we approach the university district—the clang of hammers fades, replaced by murmured discussions and occasional recitation. It's like moving from the workshop to the library, each zone having its appropriate acoustic environment. Medieval urban design considered noise pollution too.

Dar Boutouille from Place Seffarine towards Al Quaraouiyine Mosque Madrasa University showing urban connectivity between different functional zones

|

| Dar Boutouille towards Alqarawiyyeen Mosque and University showing final approach to one of world's oldest continuously operating educational institutions |

Mosque and University of al-Qarawiyyin

Kairaouine Mosque, University and Library

Al-Karaouine visitor information display showing the architectural grandeur that awaits - the sign itself is practically a work of art

The University of Al Quaraouiyine in Fez holds the incredible title of world's oldest continuously operating university - certified by both UNESCO and the Guinness Book of World Records. Think about that for a moment: when this place was already 200 years old, Oxford and Cambridge weren't even a glimmer in anyone's eye.

What's fascinating is how this place evolved from a simple mosque into a full-fledged university. In the Islamic tradition, mosques were centers of learning from the beginning, but Al-Qarawiyyin took it to another level, developing structured courses, libraries, and yes - the world's first system of academic degrees. Medieval students here were basically getting certified while Europe was still figuring out literacy.

The first glimpse through the entrance doors reveals why this place took 1,200 years to perfect - that courtyard view is basically medieval Instagram gold

The 9th century Mosque and University of al-Qarawiyyin isn't just a monument - it's the beating heart of Fez's Medina. We're talking about the cultural, religious, and intellectual center of Morocco for over a millennium. Walking through these doors feels like stepping into a time machine set to "Golden Age of Islamic Civilization."

Here's where it gets even more interesting: this whole incredible complex was founded in 857 CE by a woman named Fatima al-Fihriya, a refugee from Tunisia who used her inheritance to build something lasting. She's basically the patron saint of "when life gives you lemons, build a UNESCO World Heritage site." Subsequent sultans kept expanding and decorating, creating the masterpiece we see today.

The entrance courtyard - where every tile and arch whispers "we've been doing this geometry thing for 1,200 years and yes, we're showing off"

Al-Qarawiyyin developed into an intellectual powerhouse that would make modern Ivy League schools blush. For centuries, this was where the great minds of mathematics, astronomy, medicine, philosophy, and Islamic studies came to push the boundaries of knowledge. The library here contains manuscripts so precious they make the Vatican Archives look like a yard sale.