Trans-America USA + Mexico Overland 9,000-mile 31-day Roadtrip | Part 16 | A Sacred Landscape, Monuments to Gods & Ancient Whispers: Monument Valley, Valley of the Gods, Mexican Hat, Gooseneck State Park, Bluff, Utah to Durango, Colorado

|

| John Ford Point, Monument Valley |

Good morning, fellow wanderers! It’s us, the Vagabond Couple, back with what might be the most visually stunning couple of days of our entire 9,000-mile odyssey. We spent last night at Page after exploring Slot Canyons & Sacred Lands | Glen Canyon, Lake Powell, Antelope Canyon, Tuba City & Ghosts of Route 66 on Hwy 89 to Flagstaff. We started this day by trading pavement for red dirt, skyscrapers for sandstone monoliths and ordinary roads for the sacred lands of Monument Valley - a place where the Earth itself feels holy. Buckle up, because this episode, also covering Valley of the Gods, the double bend of San Juan river at Gooseneck State Park, Alhambra Rock, Mexican Hat Rock, historic city of Bluff, Utah, Mesa Verde National Park, city of Durango, Colorado and much more, is a love letter to the most iconic sights in stunning American Southwest, complete with cinematic vistas, Navajo wisdom and Shehzadi (our trusty Toyota Tundra) earning herself still more off-road stripes.

The Road to Monument Valley: Highway 163’s Grand Entrance

|

| Arizona - Utah border on US-163 Scenic Highway with Monument Valley, Arizona in background |

We left Page, AZ at dawn, heading east first on Arizona state route AZ-98, followed by federal highway US-160 and then on northbound Scenic Highway US-163 towards Monument Valley. Almost immediately, the landscape began its transformation; flat desert gave way to towering sandstone buttes, their ridges sharp against the morning sky. As we briefly crossed into Utah before the road dips back into Arizona like a playful border dance, the true spectacle began.

The iconic buttes and mesas in and around Monument Valley stand as a testament to the region's dramatic geological history. Their layered appearance, a hallmark of the Colorado Plateau, reveals strata of sandstone, shale and siltstone deposited over millions of years. These horizontal layers, sculpted by erosion from wind and water, create the mesas' characteristic flat top and steep cliffs. The vibrant red hues are primarily due to iron oxides, which coat the sand grains and contribute to the area's iconic desert landscape.

Sacred Landscape of the Ancient Anasazi, Monuments to Gods & Connection to the Cosmos

In Navajo tradition, these formations are not merely geological features, but sacred landmarks imbued with spiritual significance. Sentinel Mesa (the long thin cliff seen while entering the valley), for example, is known as "Tsé biiʼ Ndzisgaii" in Navajo, which translates to "White Streak Between the Rocks". The formations are often associated with stories of the ancient ones, the Anasazi, who once inhabited the region.

|

| Sentinel Mesa, the Mittens & other Monument Valley formations seen from Scenic Hwy 163 |

Legends speak of these mesas as dwelling places of powerful spirits and natural forces, placing them within a larger tapestry of Navajo cosmology where the land itself is a living history, a sacred space connecting the Navajo people to their ancestors and the spiritual world.

Agathla Peak

Agathla Peak appeared first as we drove up towards the Arizona-Utah border and Monument Valley. This well-known formation is a volcanic spire rising 1,500 feet.

|

| Agathla Peak Photo: wikimedia |

Agathla Peak is sacred to the Navajo as "the place where the gods gather". Its jagged black rock contrasted violently with the red earth - a geological exclamation point.

|

| Arizona-Utah border on US-163 Scenic Highway with Monument Valley, Navajo Nation in background |

The iconic West and East Mitten Buttes and Merrick Butte formations subsequently appeared, their distant silhouettes so perfect they looked sculpted by divine hands. The Navajo call them "Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii" (Valley of the Rocks) and according to legend, they’re the remains of ancient warriors turned to stone.

The road itself was a ribbon of asphalt cutting through a painter’s palette of ochre, crimson and gold. Every curve revealed a new wonder and we pulled over so often that Shehzadi’s hazard lights got a workout.

Monument Valley Scenic Drive: 17 Miles of Holy Ground

|

| Main Monument Valley Rd towards Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park |

At the Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park entrance, we paid our fee ($20 per person - worth every penny) and shifted Shehzadi into 4WD to take on the challenge Indian Rte 42.

|

| Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park |

The legendary unpaved 17-mile Monument Valley Loop (Indian Route 42) ahead was notorious for its washboard ruts and fine, flour-like dust that swallows tires whole in wet weather. But today, under a blistering July sun, the road was bone-dry, with potholes deep enough to lose a small child in.

|

| Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park |

Here’s a partial play-by-play of this sacred drive.

The Mittens & Sentinel Mesa

|

| The Mittens & Sentinel Mesa, Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park |

Up close, these monoliths were colossal. The Navajo believe the Mittens are hands of the Great Spirit and the Elephant Butte’s trunk-like formation is said to be a petrified mammoth from the First World.

|

| Sentinel Mesa, Monument Valley |

Mittens & Merrick Butte

The Mittens & Merrick Butte are iconic sandstone formations in Monument Valley, characterized by their towering, mitt-like shapes and rugged beauty.

|

| Mittens & Merrick Butte, Monument Valley |

Set against the vast desert landscape, they create a breathtaking, quintessential Wild West vista, especially stunning at sunrise or sunset.

|

| West Mitten Butte, Monument Valley |

West Mitten Butte is a striking sandstone formation in Monument Valley, famed for its distinctive "thumb" that gives it the appearance of a giant mitt rising from the desert.

|

| East Mitten Butte, Monument Valley |

Amazingly, East Mitten Butte complements West Mitten Butte perfectly!

Merrick Butte stands proudly between the West and East Mittens, its sharp, rugged spire complementing their iconic mitt-like silhouettes in Monument Valley's timeless desert landscape. Merrick Butte is named after Ernest A. Merrick, a prospector and guide who was killed in the area in the late 19th century during a conflict with Navajo tribesmen.

|

| Merrick Butte, Monument Valley |

Merrick Butte's name preserves his memory, along with nearby Mitchell Butte, named after his companion, Robert "Bob" Mitchell, who died in the same incident. This tragic event is part of Monument Valley's history, though the exact details remain debated among historians.

|

| View from Mittens & Merrick Butte Viewpoint, Monument Valley |

Today, the buttes stand as striking landmarks in Navajo Nation, their names echoing a complex past.

Elephant Butte

|

| Elephant Butte, Monument Valley |

The Elephant Butte Viewpoint offers a closer view of the massive Elephant Butte sandstone formation in Monument Valley. It is named for its resemblance to a giant elephant resting in the desert.

Standing tall among the iconic red mesas and buttes of the Navajo Nation, it is a striking example of the region’s rugged beauty, shaped by millions of years of erosion.

|

| Elephant Butte, Monument Valley |

John Ford’s Point

|

| John Ford Point, Monument Valley |

Named for the director who made Monument Valley famous in Westerns, the John Ford Point overlook is where John Wayne once galloped across the silver screen. We rented a horse here from a local Navajo gentleman!

Thunderbird Mesa

|

| Thunderbird Mesa, Monument Valley |

Thunderbird Mesa is a majestic 5,814 foot sandstone formation in Monument Valley, renowned for its towering presence and sacred significance to the Navajo people. Named after the powerful Thunderbird - a revered spirit in Navajo mythology associated with storms and strength - this mesa stands as a striking landmark against the vast desert sky. Its rugged cliffs and deep red hues glow brilliantly at sunrise and sunset, making it a favorite subject for photographers. Visitors often admire Thunderbird Mesa along the Valley Drive or from iconic viewpoints like Artist’s Point.

Rain God Mesa

|

| Rain God Mesa, Monument Valley |

Named for its spiritual significance to the Navajo people, the iconic Rain God Mesa rises dramatically from the desert floor, showcasing the region's stunning red rock formations. According to Navajo tradition, the Rain God Mesa is sacred, believed to influence weather and bring life-giving rain to the land.

|

| East aspect of Rain God Mesa seen later when coming back up around the loop |

The Three Sisters

Three slender spires that resemble nuns in prayer. Legend says they’re frozen Diné maidens who refused to abandon their homeland.

|

| Three Sisters, Monument Valley |

The Three Sisters stand as a striking trio of sandstone spires in Monument Valley, steeped in a poignant Navajo (Diné) legend. These formations are said to be frozen figures of a mother and her two daughters who were turned to stone by the Holy People during a great drought.

As the story goes, the family refused to abandon their ancestral land even as the earth cracked with thirst. Taking pity on their devotion, Estsanatlehi (Changing Woman) transformed them into eternal sentinels - their pleated skirts and woven hair still visible in the rock’s layers. At noon, when their shadows merge into one, elders say the sisters briefly reunite in spirit.

|

| Three Sisters, Monument Valley |

Navajo guides often leave blue cornmeal at the base as an offering, reminding visitors that these aren’t just rocks - they’re a family still watching over the valley.

Some clans associate the sisters with the constellations of Dilyéhé (Pleiades), linking earth and sky.

Totem Pole & Yei Bi Chei

The Totem Pole is one of Monument Valley's most iconic and slender sandstone spires, towering dramatically over the desert landscape. This striking formation, reaching over 400 feet tall, is a sacred site for the Navajo people and a legendary challenge for rock climbers - only a few elite climbers, like Dean Potter, have ever scaled its narrow peak.

|

| Totem Pole & Yei Bi Chei, Monument Valley |

Yei Bi Chei is another striking sandstone spire in Monument Valley, named after the sacred Yé’ii Bicheii (Holy People) of Navajo tradition. These towering rock formations resemble the spiritual dancers who perform in Navajo healing ceremonies, connecting the physical world to the divine. This sacred site holds deep cultural significance, often featured in Navajo rituals and stories. It is said on quiet nights, you can hear their ceremonial chants in the wind.

Rooster Rock

|

| Rooster Rock and Yei Bi Chei at Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park |

Rooster Rock is another distinctive sandstone spire in Monument Valley, named for its unique shape resembling a rooster's comb. This striking formation, sculpted by wind and erosion over millions of years, stands proudly near other iconic landmarks like Totem Pole and Yei Bi Chei.

|

| Rooster Rock, Monument Valley |

Rooster Rock and the other formations' red-orange hues glow intensely during sunrise and sunset, making them a favorite subject for photographers and artists. Sacred to the Navajo people, Rooster Rock holds cultural significance.

|

| Monument Valley view from here |

The Cube

|

| The Cube, Monument Valley |

The Cube is one of Monument Valley's lesser-known but mesmerizing sandstone formations, named for its strikingly geometric, block-like shape.

|

| The Cube, Monument Valley |

Unlike the valley's towering spires and mesas, this unique formation stands out for its near-perfect cubic structure, carved over millennia by wind and erosion.

|

| The Cube, Monument Valley |

The Cube of Monument Valley is located off the main Valley Drive but easily discovered. At sunrise and sunset, The Cube's sharp angles cast dramatic shadows across the desert, creating a surreal contrast against the sweeping red landscape.

|

| View of Monument Valley on the side opposite to the Cube |

Spearhead Mesa

|

| Spearhead Mesa, Monument Valley |

Spearhead Mesa rises defiantly from the desert floor in Monument Valley, its sharp, blade-like silhouette evoking the spear of a warrior. According to Navajo legend, this striking formation was once a celestial weapon thrown by the Hero Twins, Naayééʼ Neizghání (Slayer of Alien Gods), to pierce the earth and vanquish evil spirits. The mesa's sheer cliffs and rust-red hues glow like embers at dusk, a reminder of its sacred role in Diné (Navajo) cosmology.

|

| Monument Valley sandstone formations viewed on opposite side of Spearhead Mesa |

Today, it stands as a silent guardian, visible from viewpoints like John Ford’s Point, where visitors honor its power through photographs - never climbing, as the Navajo consider it holy ground.

|

| Spearhead Mesa seen from Balanced Rock |

Balanced Rock

"The rock doesn’t defy gravity - it defies despair" - Navajo elder.

|

| Balanced Rock at mid-day, its massive capstone glowing crimson, seemingly suspended by ancient magic. |

The Balanced Rock of Monument Valley is another gravity-defying sandstone wonder near Spearhead Mesa, woven into Navajo (Diné) legend as a sacred marker placed by the Holy People.

|

| Balanced Rock in front of Spearhead Mesa, Monument Valley |

According to oral tradition, the precarious boulder was set atop its slender pedestal by Tséghádiʼnídíinii (the Rock Spirit Eagle) as a test of balance - both physical and spiritual. It is said the rock will only fall when the world is out of harmony, serving as a reminder to live in accordance with Hózhǫ́ (beauty and balance).

At dawn, the formation casts elongated shadows across the valley, appearing to float above the earth.

Artist’s Point

Where the valley unfolds like a living Georgia O’Keeffe painting. The play of light and shadow at midday made the rocks seem to breathe. From this vantage point, visitors can see some of Monument Valley’s most famous formations.

|

| Artist’s Point, Monument Valley |

Artist’s Point in Monument Valley is one of the most iconic viewpoints in the Navajo Tribal Park, offering a breathtaking panoramic view of the valley’s towering sandstone formations. This spot is named for its picturesque beauty, which has inspired countless artists, photographers and filmmakers (most famously, director John Ford in his Western films).

The Thumb

|

| The Thumb, Monument Valley |

The Thumb, a towering sandstone spire in Monument Valley, is steeped in Navajo (Diné) legend as a sacred marker of protection.

|

| The Thumb, Monument Valley |

According to oral tradition, this formation represents the clenched fist of Áłtsé Hastiin (First Man), who thrust his hand from the earth to shield the Diné people during a great battle against the Anaye (monsters).

|

| The Thumb, Monument Valley |

The ridges and cracks in the rock are said to be the wrinkles of his skin, frozen in time as a reminder of ancestral strength.

|

| Shehzadi posing before The Thumb, Monument Valley |

At sunset, when the Thumb glows like burning coal, elders whisper that it still pulses with the heartbeat of the Holy People.

|

| The Thumb, Monument Valley |

Never attempt to climb the sacred formations at Monument Valley, including the thumb. As Navajo elders told us, "to disturb the Thumb is to awaken old giants".

North Window Overlook

|

| North Window Overlook, Monument Valley |

North Window Overlook frames one of Monument Valley’s most sacred vistas - a natural stone arch believed by the Navajo (Diné) to be the Eye of Changing Woman (Asdzą́ą́ Nádleehé). Legend tells that she peered through this portal during the Fourth World’s creation, watching as the Holy People sculpted the valley’s spires from sunlight and clay.

|

| North Window Overlook, Monument Valley |

Changing Woman’s tears, shed here during a great drought, are said to have formed the hidden Quicksand Springs beneath the overlook.

The "window" aligns perfectly with the summer solstice sunrise, when light pours through like molten gold, symbolizing her eternal renewal of life. Diné families leave offerings of turquoise dust here for fertility blessings and guides caution against passing through the arch - "what the goddess watches, humans should not trespass".

|

| North Window Overlook, Monument Valley |

"We don’t take pictures of the Window - we let the Window take pictures of us" - Navajo photographer, 2022.

The 17-mile Monument Valley loop drive took us three hours - not because of distance, but because every turn demanded reverence. Once again, the Navajo ask visitors not to climb the formations (they’re alive, not playgrounds) and we of course honored that.

Completing the loop leaves an indelible imprint on the soul - a mosaic of towering sandstone sentinels, crimson dust swirling around your boots and the whispers of ancient winds carrying Diné prayers. The journey etches itself into memory: the way Totem Pole’s shadow stretches like a sundial at dusk, the scent of sage after rain near Artist’s Point and the sudden silence when you stand alone before West Mitten Butte, its silhouette mirroring your smallness in time.

|

| Looking back at Monument Valley from Northbound US-163 Scenic Highway |

The Navajo often say the valley doesn’t let you go unchanged; you’ll dream of juniper shadows painting the sand, wake craving fry bread from Goulding’s and forever measure sunsets by how fiercely the rocks burn. This is not just scenery - it’s a living story you’ve stepped into, one that lingers like red earth under your nails.

Monument Valley 17-mile Loop Drive Dashcam Video Recording

Here is a complete dashcam video from Shehzadi negotiating the entire 17-mile Monument Valley Scenic Road loop:

Watch: Driving the Monument Valley 17 Mile Loop Scenic Road Off-road Trail: Complete Dashcam Footage

Tip: Keep a pinch of Monument Valley sand in your pocket - Navajo tradition says it ensures your return.

Scenic Highway 163 North into San Juan County, Utah: A Cinematic Pilgrimage

Back on paved road, we continued northeast into Utah, where Scenic Highway 163 became a film reel of iconic landscapes as we headed deeper into San Juan County, Utah - a breathtaking tapestry of red rock deserts, deep canyons and sacred Indigenous landscapes, spanning over 7,900 square miles of the Colorado Plateau. This is home to iconic wonders like Monument Valley’s towering buttes, the winding San Juan River and the otherworldly Goosenecks State Park, this remote region is the heart of Navajo (Diné) and Ute cultural heritage. Visitors explore ancient Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings at Natural Bridges National Monument, trek through the sandstone labyrinths of Canyonlands’ Needles District, or stargaze in the certified Dark Sky communities of Bluff and Mexican Hat.

Yet beyond the postcard vistas, San Juan County carries complex layers of history - from the 19th-century Hole-in-the-Rock Mormon expedition to ongoing efforts to honor Native sovereignty and protect fragile ecosystems. Here, the land whispers in Diné Bizaad (Navajo) and every dirt road leads to adventure, solitude, or a lesson in resilience.

San Juan county contains more wilderness area than the entire state of Connecticut!

Forrest Gump Point

|

| Forrest Gump Point |

The exact spot where Tom Hanks’ character stopped running, saying "I'm pretty tired. I think I'll go home now." in Forrest Gump (1994). We recreated the scene (sans running), with the road stretching infinitely toward the Mittens.

|

| "I'm pretty tired. I think I'll go home now." Scene from Forrest Gump (1994) - Tom Hanks |

Nearby, the brick arch from Once Upon a Time in the West still stands - a relic of Hollywood’s love affair with this land.

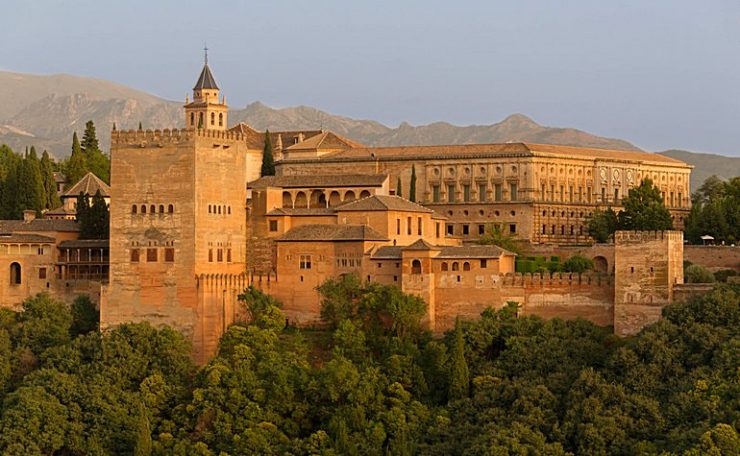

Alhambra Rock

|

| Alhambra Rock, San Juan County, Utah |

A lone, fortress-like mesa named by Spanish explorers who thought it resembled the Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain. The Navajo call it "Tségháhoodzání" (the Rock with Wings), tied to a story of a great bird that sheltered their ancestors.

|

| Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain: do you see the similarity with Alhambra Rock in Utah, USA? |

The rugged Alhambra Rock in Utah’s Valley of the Gods gets its name from its uncanny resemblance to Spain’s Alhambra Palace in Granada, but the connection runs deeper than just a passing similarity. Like the palace’s red fortress walls (built from rammed earth), Alhambra Rock’s Cedar Mesa Sandstone has a warm, terracotta hue and a craggy, fortress-like profile. Both feature layered "tiers", the palace’s ornate courtyards mirror the rock’s stepped erosion patterns. At sunset, the rock glows rose-gold, just like the Alhambra’s famous "Golden Hour", when its towers reflect the Sierra Nevada’s light.

|

| Alhambra Rock |

There are also Navajo & Moorish Parallels. To the Diné (Navajo), the rock is a sacred sentinel, much like the Alhambra was a spiritual stronghold for Nasrid sultans. Both sites are imbued with prayers - Navajo corn pollen offerings here, Arabic calligraphy there.

Ironically, the Alhambra Palace is a man-made oasis of gardens and water, while Alhambra Rock is a wind-sculpted desert monolith - yet both feel equally mystical.

|

| Alhambra Rock |

In local lore, early Anglo explorers named it while dreaming of Old World wonders... or maybe they just really missed Spain. Either way, the name stuck!

Mexican Hat Rock

|

| Mexican Hat Rock |

Mexican Hat is basically a big sandstone pancake from the Cedar Mesa layer, plopped on top of a crumbling red dirt pedestal made of Halgaito shale. Both these rock layers are part of the ancient Cutler Group – we're talking dinosaur-old here, from way back in the Permian days over 250 million years ago. Picture a giant sombrero made of stone sitting on a rusty red cone that's slowly sloughing off into the valley below.

|

| Mexican Hat Rock |

This is a 60-foot precariously balanced rock that looks like a sombrero perched on a pedestal. Local lore claims it’s the hat of a sleeping giant - disturb it and he’ll wake angry.

|

| Shehzadi poses with Mexican Hat Rock |

That iconic sandstone cap is freakishly heavy - geologists ballpark it at around 3.4 million pounds (1,500+ metric tons)! Here’s the math:

- Dimensions: ~60 feet wide × 12 feet thick (like a 2-story pancake)

- Sandstone Density: ~150 lbs/ft³

- Volume: Roughly 22,500 ft³

- Total Weight: 1.5 kilotons (or about 1,000 pickup trucks)

Also, it’s not just sitting there; it’s glued by ancient mineral deposits and sheer luck. The softer Halgaito shale beneath it erodes about 1 inch per century, so the "hat" might eventually topple... but probably not in our lifetime. Some Navajo elders say the weight isn’t just physical; it’s the spiritual weight of the Hero Twins’ promise to protect the land. Heavy stuff, literally and metaphorically.

|

| Mexican Hat Rock |

Geologically, this iconic landmark was sculpted over millions of years as wind and water eroded the softer layers of the Halgaito Shale and Cedar Mesa Sandstone, leaving the resistant Organ Rock Formation to form the "hat's" brim.

|

| Mexican Hat Rock |

To the Navajo (Diné), the rock is known as "Tsé Ta’á" (Rock Head) and is tied to legends of the Hero Twins, who are said to have placed it there as a marker during their battles with monsters. Some elders whisper that the rock tilts further whenever disharmony grows in the world, acting as a natural pendulum of balance.

|

| Mexican Hat Rock |

The nearby San Juan River curves beneath it like a sacred serpent, adding to the site’s spiritual significance. Visitors can hike the short trail around its base or witness its fiery glow at sunset - though climbing is discouraged, as the formation is considered a sentinel of the ancestral world.

|

| Mexican Hat Rock |

The snow-capped peaks of the Carrizo Mountains can be seen in the distance.

Gooseneck State Park: The San Juan River’s Double Bend

|

| Gooseneck State Park: San Juan River Double Bend |

A short detour took us to Gooseneck State Park, where the San Juan River carves two 1,000-foot-deep meanders (bends) into the earth.

|

| Gooseneck State Park: San Juan River Double Bend (panorama) |

The Navajo name for this bend, "Tó Naneesdizí", means "tangled waters", referencing the river’s stubborn refusal to flow straight!

Standing at the overlook, we traced the water’s path - a liquid labyrinth older than human memory. The San Juan River begins as snowmelt and alpine springs in the San Juan Mountains of southern Colorado (near Wolf Creek Pass, elevation ~10,850 ft). Its headwaters gather in Bristol Head (a subrange of the Rockies) and merge near Pagosa Springs, Colorado - a town famous for its geothermal aquifer, which adds warm mineral flows to the river’s early course. The river flows 382 miles southwest through:

- Colorado: Carves deep into Dolores Formation shale, creating trout-rich stretches like the "Quality Waters" near Pagosa

- New Mexico: Cuts through the Navajo Nation, filling Navajo Lake Reservoir (critical for irrigation)

- Utah: Forms the Goosenecks of the San Juan (this 1,000-ft-deep meander canyon!) and joins the Lake Powell reservoir at Glen Canyon Dam

|

| Shehzadi at Gooseneck State Park San Juan River Double Bend Overlook |

Officially, the San Juan river empties into the Colorado River now submerged under Lake Powell near Halls Crossing. Historically, it flowed freely to the Grand Canyon, but dams (like Navajo Dam) have reduced its sediment load by ~90%, altering ecosystems downstream.

Flash floods (like the 1911 Carracas Canyon flood) can swell the San Juan river from 500 to 30,000 CFS in hours. The river also carries uranium traces from abandoned Cold War mines near Shiprock - a lingering environmental issue.

San Juan Inn & Trading Post: A Night in the Wild West

|

| San Juan Inn & Trading Post, Mexican Hat, Utah |

As the sun dipped below the Valley of the Gods (tomorrow’s adventure!), we pulled into Mexican Hat, UT, population: 31!

|

| San Juan Inn & Trading Post, Mexican Hat, Utah |

Our lodging at the San Juan Inn & Trading Post was a time capsule - a 1920s trading post turned motel, with creaky wood floors and a porch overlooking the San Juan River.

|

| San Juan Inn & Trading Post, Mexican Hat, Utah |

At dinner (fry bread taco at the attached San Juan Cafe), we met a Navajo elder who told us about the Hero Twins who slayed monsters in these canyons. "The rocks remember," he said, pointing to the cliffs. "You just have to listen."

|

| San Juan Inn & Trading Post |

Petroglyphs

On the rock behind the San Juan Trading Post at Mexican Hat, we saw our first Petroglyphs. The petroglyphs of southern Utah are remarkable ancient artworks carved into rock surfaces by Native American cultures, including the Fremont, Ancestral Puebloans and later Ute and Navajo peoples.

|

| Petroglyphs at Mexican Hat |

These intricate designs, dating back thousands of years, depict animals, human-like figures and abstract symbols, offering a glimpse into the spiritual and daily lives of the region's early inhabitants.

|

| Petroglyphs at Mexican Hat |

Found in numerous places all across southern Utah, including Newspaper Rock, Nine Mile Canyon and Capitol Reef National Park, these petroglyphs were created using stone tools to chip away the dark desert varnish, revealing lighter rock beneath.

|

| Petroglyphs at Mexican Hat |

Many of the carvings remain shrouded in mystery, with their exact meanings lost to time, yet they continue to hold cultural significance for modern Indigenous communities.

|

| Petroglyphs at Mexican Hat |

Protected as sacred heritage sites, these petroglyphs serve as a powerful connection to the past and a testament to the enduring artistry of Utah's earliest residents.

The next day, we woke before dawn at the San Juan Trading Post, the scent of juniper woodsmoke drifting through our window. Outside, the San Juan River glowed silver in the first light and Mexican Hat Rock stood sentinel over the sleepy hamlet. Today, we’d trade civilization for the raw, untamed beauty of Valley of the Gods, a landscape so surreal it makes Monument Valley look tame. Coffee in hand, we fired up Shehzadi - her red dust from yesterday’s adventures still clinging like war paint - and crossed the river toward Route 261.

WASATCH Signs

Driving through southern Utah, we spotted some mysterious round signs mounted high on rocky cliffs and canyon walls marked boldly with the word "WASATCH" and the profile of a Native American in a feathered headdress.

|

| WASATCH sign at tiny hamlet of Mexican Hat in Southern Utah |

These iconic markers date back to the mid-20th century when the Wasatch Line, a regional travel and transport company, placed them to advertise scenic destinations across the American Southwest. Though now faded and weather-worn, the signs have become nostalgic symbols of vintage Americana road-tripping, blending kitschy roadside charm with stunning natural backdrops.

For many travelers, spotting a Wasatch sign feels like finding a little piece of hidden highway history, whispering stories from an era when the open road promised endless adventure and discovery.

Valley of the Gods: Monument Valley’s Wild Sister

We enter the Valley of the Gods via its West entrance to drive its stunning 17-mile loop to eventually exit at the East Entrance. The United States Bureau of Land Management (BLM) plays a crucial role in maintaining the Valley of the Gods, a stunning red-rock desert landscape in southeastern Utah. As part of its stewardship, the BLM ensures the preservation of the area's natural beauty, geological formations and cultural significance while managing recreational activities such as hiking, camping and off-road vehicle use.

|

| Valley of the Gods West Entrance |

The BLM works to balance public access with conservation efforts, protecting fragile desert ecosystems and Indigenous cultural sites. Through minimal infrastructure - such as primitive campsites and unmarked trails - the BLM maintains the valley's rugged, undeveloped character, allowing visitors to experience its remote and awe-inspiring scenery responsibly. Their efforts help sustain this iconic region for future generations while promoting sustainable tourism and environmental education.

|

| Valley of the Gods |

The West Entrance to Valley of the Gods appeared suddenly: an unmarked turnoff onto a 17-mile dirt loop that winds through a maze of 400-foot sandstone monoliths.

|

| Valley of the Gods |

Unlike its famous neighbor, this valley has no guardrails, no tour buses - just a rugged, unpaved road and the kind of silence that hums in your bones.

|

| Valley of the Gods |

Valley of the Gods, a breathtaking landscape in southeastern Utah, is a striking expanse of towering sandstone buttes, mesas and spires sculpted by millions of years of geological forces.

|

| Valley of the Gods |

Part of the Colorado Plateau, its formations were shaped by the same ancient seas, wind and water erosion that created nearby Monument Valley.

|

| Valley of the Gods |

The red and orange hues of the Cedar Mesa Sandstone and Halgaito Formation reveal layers of sediment deposited over 250 million years ago during the Permian Period.

|

| Valley of the Gods |

Culturally, the valley holds deep significance for the Diné (Navajo) people, who consider it sacred and part of their ancestral homeland.

|

| Valley of the Gods |

While it lacks the density of archaeological sites found in places like Bears Ears, scattered Ancestral Puebloan artifacts and petroglyphs suggest temporary habitation or travel routes over a thousand years ago.

|

| Valley of the Gods |

Later, the Ute and Paiute tribes also traversed the region.

|

| Valley of the Gods |

Unlike its more famous neighbor, Monument Valley, Valley of the Gods remains relatively undeveloped - a quiet, remote sanctuary for hiking, stargazing and reflection.

|

| Valley of the Gods |

The preservation of the stunning and unique Valley of the Gods is now part of broader conservation efforts, balancing respect for Indigenous heritage with responsible public access to this otherworldly desert landscape.

Valley of the Gods Road: A Drive that is a Dance with Dust & Stone

|

| Valley of the Gods |

July’s heat had baked the clay into a cracked mosaic. Shehzadi’s tires kicked up clouds of rust-colored dust so fine it hung in the air like mist. Deep ruts and occasional softball-sized rocks kept us at a cautious 15 mph - this was no place for low-clearance cars.

Sacred Rules

|

| Valley of the Gods |

The Navajo ask visitors not to name the formations (they’re not tourist attractions but living beings), so we admired them as the Diné do: with quiet reverence. There are innumerable standout formations in the Valley of the Gods - every mile reveals stunning out-of-the-world wonder. Here are just three examples!

|

| Valley of the Gods |

Seven Sailors

|

| Seven Sailors, Valley of the Gods |

A cluster of slender spires said to be frozen Navajo warriors who defended this land. At sunrise, their shadows stretch like compass needles.

|

| Seven Sailors, Valley of the Gods |

Castle Butte

|

| Castle Butte |

Castle Butt rises like a crumbling sandstone fortress, its jagged spires and fluted walls carved from De Chelly Sandstone - the same 250-million-year-old layer that forms Monument Valley’s iconic buttes. Wind and water have sculpted its "turrets" and "moat-like" gullies, exposing cross-bedded stripes of ancient dunes frozen in stone. To the Navajo (Diné), this formation is "Tsé Naajinii" (Black Streak Rock), named for the dark mineral veins streaking its face, believed to be the scorch marks of Lightning People (Iį́į́h) who struck the rock to release trapped rain spirits.

|

| Castle Butte |

Viewed from the side along the valley’s dirt loop road, Castle Butt appears as a solitary sentinel, its shadow stretching like a sundial across the desert - a silhouette elders say mirrors the profile of a Diné warrior turned to stone for defying the gods.

|

| Castle Butte from the side |

At dusk, when the rock glows like embers, some whisper they hear drumbeats echoing from its hollows, a remnant of ceremonial chants still sealed in the stone.

Geologically, this "castle" is softer than it looks - its base crumbles 10x faster than its caprock. Time is literally eating its walls.

Lady in Bathtub

|

| Lady in a Bathtub, Valley of the Gods |

A butte resembling a woman reclining in a tub. Local lore claims she’s a goddess who bathes in moonlight.

|

| Lady in the Bathtub, Valley of the Gods |

Sleeping Ute Mountain

|

| Valley of the Gods (panorama) |

Visible to the east, this mountain’s profile mirrors a resting warrior. The Ute people believe it’s their ancestor, guarding the valley.

As we crawled along the loop, turkey vultures circled overhead - the only other souls in this cathedral of stone. Finally reaching the East Entrance, we merged back onto US-163, the valley’s spires shrinking in our rearview like a receding dream.

|

| Shehzadi exiting at East Entrance of Valley of the Gods |

Valley of the Gods Road 17-mile loop Dashcam Video Recording

Watch the video recording from Shehzadi's dashcam as we drove the 17-mile Valley of the Gods Road loop:

Watch: Driving the Valley of the Gods Road, Mexican Hat, San Juan County, Utah: Ancient Historic & Sacred

Bluff, UT: Established 650 AD - Where History Still Breathes

An hour northeast brought us to Bluff, Utah, a time capsule from the ancient to the Old West to modern, wedged between sandstone cliffs.

|

| Bluff, Utah |

The "Established 650 A.D." sign in Bluff, Utah, is a nod to the region’s deep Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi) roots - long before Mormon pioneers arrived in 1880. Around 650 A.D., the Basketmaker III culture (early Ancestral Puebloans) began building pit houses and farming along the San Juan River, leaving behind artifacts and rock art. By 750 - 1300 A.D., they constructed cliff dwellings like those at nearby Bears Ears and Butler Wash, evidence of a sophisticated agricultural society. The sign’s date honors the continuous human habitation of the area for over 1,300 years - from ancient Puebloans to Navajo (Diné) and Ute peoples, to Anglo settlers. The sign is also a rare acknowledgment of Indigenous history in a town often associated with pioneer lore.

Local Navajo refer to the area as "Dinétah" (traditional homeland), with oral histories tying clans to the land long before Europeans arrived. Bluff’s sandstone cliffs still hold petroglyphs of Puebloan spirals and Diné Ye’ii (holy people), making the town a living museum.

The sign subtly challenges the "Wild West" narrative, reminding visitors that this land’s story didn’t start with cowboys - it started with corn, cliffs and cosmic rock art.

|

| Bluff Fort |

Modern Bluff was founded in 1880 by Mormon pioneers (who nearly starved trying to tame this land), Bluff wears its recent history on its sleeve. Bluff Fort is a reconstructed 1880s settlement with original cabins and wagons. It is not really anything like a fort. You can touch some bullet holes in the old post office door - reminders of tensions between settlers and Navajo.

At the Sand Island Petroglyphs, you can trace1,000-year-old carvings of Kokopelli and bighorn sheep. Local elders tell stories of the figures being messages from the Ancestral Puebloans, warning of droughts and blessings.

|

| Sand Island Petroglyphs |

The San Juan River here is called "Tó Díkʼǫ́ǫ́zh" (Sacred Water) by the Navajo. You can dip your hands in its current - a ritual for safe travels!

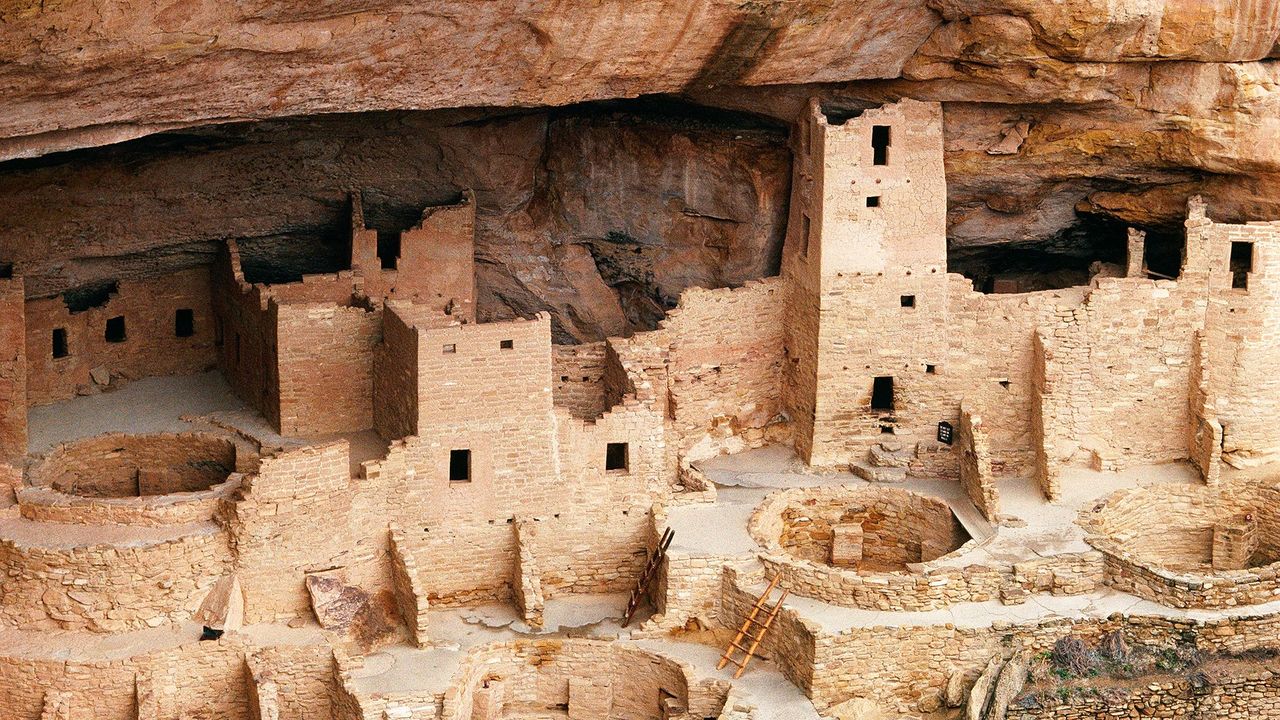

Mesa Verde National Park: Cliff Dwellings in the Sky

From Bluff, Utah, we crossed the border into southern Colorado, thus coming full circle from northern Colorado a seemingly long time ago and having since covered a vast distance across Utah, Nevada, California and Arizona in our 9,000-mile road trip - a story we wrote down starting at Topeka, Kansas to Colorado Springs, Colorado - Pikes Peak Summit, Garden of the Gods & More.

Mesa Verde National Park awaited like a mirage. This UNESCO site protects 600 Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings tucked into ochre-hued alcoves. It is indeed mind-blowing.

|

| Mesa Verde National Park |

The Cliff Palace (the largest dwelling) housed 100 people in 150 rooms - all built by hand in the 12th century. How? No one knows for sure, but Navajo oral history speaks of the "Hisatsinom", or "Ancient Ones," who climbed sheer cliffs with toeholds no wider than a finger.

By 1300 CE, the Puebloans vanished! Archaeologists blame drought; Navajo legends whisper of a Great Migration ordered by the spirits. Standing in the ruins, you can feel the weight of their absence.

Durango: Nightfall in the Rockies

|

| Durango, Colorado |

As dusk painted the La Plata Mountains gold, we rolled into Durango, Colorado - a lively town where saloons and sushi bars coexist with totally legal Marijuana joints. Over green chile-smothered burgers at Serious Texas BBQ, we plotted tomorrow’s route: south to Roswell, NM, where Aliens?! 👽🚙 & UFO lore and desert oddities await (once again after our Extra Terrestrial Highway adventures in Nevada!).

|

| Cannabis Tours flier, Durango, Colorado |

But for now, we’re savoring the echoes of today - the Valley of the Gods’ silent monoliths, Bluff’s pioneer ghosts and Mesa Verde’s cliffside puzzles. This land keeps its secrets close, but if you listen? It’ll tell you stories older than time. Next up: Landing in ROSWELL, NEW MEXICO – UFOs, Aliens, Burgers & Americana on the Outskirts of Reality!

Reference route map of The Vagabond Couple's 9,000-mile USA & Mexico overland roundtrip: Map-1 and Map-2.

— The Vagabond Couple & Shehzadi

P.S. Shehzadi’s dust coating is so thick, she looks like a red velvet cake. 🚙💨

0 comments